NASA’s InSight has likely detected its first ‘marsquake.’ Have a listen

- Share via

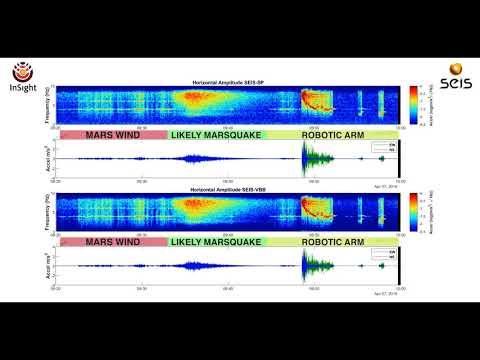

It sounds like a subway train rushing by. Or a plane flying low overhead. But it’s something much more exotic: in all likelihood, the first “marsquake” ever recorded by humans.

NASA’s InSight mission detected the quake on April 6, four months after the lander’s highly sensitive seismometer was installed on the Martian surface.

The instrument had previously registered the howling winds of the red planet and the motions of the lander’s robotic arm. But the shaking picked up this month is believed to be the first quake from Mars’ interior.

“This is the opening round of Mars seismology,” Bruce Banerdt, InSight’s principal investigator, told a rapt audience at a meeting of the Seismological Society of America on Tuesday in Seattle. Banerdt is a planetary geophysicist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada-Flintridge who has spent decades trying to study seismic activity on Mars.

Although they have much more analysis to do, seismologists are fairly confident it was an actual marsquake.

“We can’t think of anything else that it could likely be,” Banerdt said. “But you always have to put a caveat because we don’t know Mars.”

Scientists want to study how seismic waves propagate through the planet to determine its structure and composition. This will give them clues about what its internal layers look like, which in turn help them understand how the planet formed and determine the size of its core.

That goal came into reach when InSight touched down safely in November. But Banerdt and his colleagues still had to execute a series of difficult moves to deploy the seismometer.

NASA scientists and their collaborators spent the first few weeks studying InSight’s immediate surroundings and deciding where to place the instrument. By mid-December, they were ready to lower the seismometer to the ground. After that, it took more than six weeks to adjust the cable that connects the instrument to the lander and place a protective cover over the seismometer to shield it from the elements.

After years of preparation, scientists were ready to start listening to Mars.

And so began the agonizing wait.

“We all knew it was just a matter of time,” said Renee Weber, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala., and a member of InSight’s science team.

Why is Mars so different from Earth? NASA’s InSight mission will dig deep to find answers »

Collaborators in Europe are the first to see the data when it’s beamed down from the spacecraft, so Weber knew the news of a quake would come in the middle of the night for U.S. researchers.

“I always checked first thing before I got out of bed,” she said. “Is today going to be the day?”

When the day came, InSight scientists across the world gathered for a teleconference. “It was pretty clear this was very different than anything we’d seen in the two months we’d been looking,” Banerdt said.

The shaking had the characteristic slow crescendo and even slower decay of a quake. But it wasn’t exactly what scientists were expecting.

“It’s still a very bizarre signal,” Banerdt said.

For one thing, the quake lasted for about 10 minutes — much longer than a similar event would persist on Earth. Here, liquid water and water trapped in minerals help absorb energy faster. A long-lived marsquake may suggest Mars has a drier and more fractured crust, like the moon.

The temblor may have been about a magnitude 2.5 event — too small to give scientists a picture of the deep interior of Mars. It didn’t have the low-frequency signal associated with distant earthquakes, leading scientists so suspect it occurred within a few hundred kilometers of the lander.

InSight also recorded three other possible marsquakes, which were even smaller. Banerdt thinks they detected this spate of activity because conditions have been getting quieter, allowing them to identify subtle events at night when the winds die down.

Researchers don’t yet know what caused the quakes. “At this point, we haven’t ruled out any mechanisms,” Weber said.

Mars does not have tectonic plates that crash into each other — the primary cause of quakes on Earth. The most likely explanation is that the Martian crust is cracking as it cools, Banerdt said. The April 6 event does not look like a meteorite impact, but it’s too soon to say for the others.

Based on the observations so far, researchers think they will observe between six and 12 more marsquakes during the mission’s lifetime. The lander is scheduled to operate for two Earth years, though it will likely last longer if its solar-powered instruments keep working.

Weber is optimistic that InSight will eventually record more intense shaking — either from a meteorite impact or an internal source — that will give researchers a better view of the planet’s deep interior.

“It’s a waiting game,” she said. “We just have to wait until the planet cooperates.”

The extraterrestrial results sparked great interest among seismologists at the Seattle meeting. Many craned their necks to see the first Martian seismogram and snapped photos with their phones.

“From the looks of it, it’s a highly successful experiment so far,” said Doug Dreger, a UC Berkeley geophysicist who attended Banerdt’s lecture. “I hope they catch more earthquakes — well, marsquakes.”