InSight’s 300-million-mile journey to Mars has ended with a safe landing, NASA says

- Share via

After traveling 300 million miles through the solar system, NASA’s InSight spacecraft descended through the Martian sky Monday and touched down safely on the smooth surface of Elysium Planitia shortly before noon.

The news elicited cheers, high-fives and fist-bumps from the scientists and engineers assembled at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge. It means that the two-year mission to study the inside of Mars — formally called Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport — is a go.

“Touchdown confirmed,” mission commentator Christine Szalai announced at 11:54 a.m.

InSight launched from California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base in May and, after an uneventful seven-month cruise, closed in on Mars over Thanksgiving weekend. That meant engineers spent their holiday finessing the spacecraft’s final approach.

They checked and double-checked InSight’s trajectory, aiming it toward a 6-by-15-mile keyhole in the Martian atmosphere that would guide the vehicle toward a carefully chosen landing spot on the ruddy surface. On Sunday afternoon, they gave the spacecraft one final nudge.

Weather forecasts from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter showed that the outlook was sunny with a low chance of dust storms, so engineers skipped their last chance to tweak InSight’s landing procedure Monday morning. The pieces were in place; there was nothing more for Earthlings to do.

At 11:39 a.m., InSight screamed into the Martian atmosphere and, as expected, lost communication with Earth. A focused quiet fell over the rows of engineers in mission control at JPL, as everyone waited for signals confirming that InSight had made it through a series of crucial steps. Some hunched close to their computer screens, others glanced around for updates.

In this room, engineers have seen the delicate dance of entry, descent and landing go flawlessly — and fatally — on previous missions.

Unlike on previous missions, however, the InSight team had the benefit of two experimental satellites that tracked InSight’s progress. Known collectively as Mars Cube One, or MarCO, they locked onto the spacecraft before it entered the Martian atmosphere and continuously relayed information back to mission control.

The signals were delayed by the eight minutes it took for radio waves to travel from Mars, meaning InSight’s fate had already been sealed by the time anyone at JPL heard about it. Still, the team members — all clad in burgundy shirts emblazoned with the InSight logo — watched with rapt attention.

First, radio telescopes in West Virginia and Germany registered a slight change in the frequency of InSight’s signal, indicating that its parachute had inflated and the craft had slowed down. A round of applause rippled through mission control; one engineer flashed a thumbs up.

Seconds later, InSight discarded its heat shield and deployed its legs. Then it informed MarCO that its radar found the ground, again prompting restrained clapping in mission control. Two engineers turned to each other and high-fived.

“This is really good news,” said Rob Manning, JPL’s chief engineer.

After it shed its back shell and chute, InSight fired its retrorockets. Szalai kept announcing its altitude as the craft floated down to the surface: 400 meters above Mars, 300 meters, 200 meters.

The tension grew as the numbers fell. “The hairs on the back of my neck would start rising a little bit higher and a little bit higher,” said project manager Tom Hoffman.

Finally, the MarCO satellites watched as InSight touched down on the surface of Mars. Mission control erupted into cheers as engineers leaped to their feet, shaking hands and hugging.

“This never gets old,” Manning said.

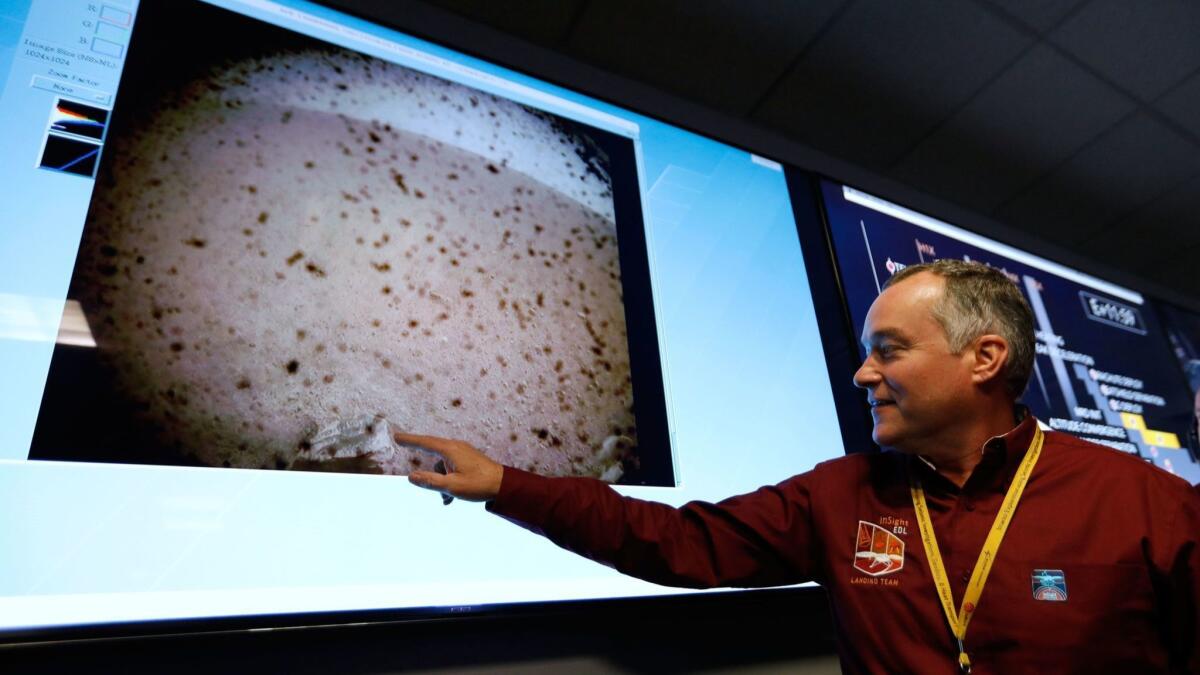

An added bonus arrived a few minutes later: MarCO transmitted a photo snapped by InSight of its new surroundings. Through the dust-speckled lens, it shows a flat surface with a rock in the foreground. InSight also caught one of its legs in the shot.

The celebrations extended far beyond JPL. There was a party in New York’s Times Square, where people huddled under umbrellas to watch a live stream of the landing in the rain. Even the astronauts on the International Space Station radioed Houston to send their congratulations.

On Monday evening, NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter confirmed that InSight successfully unfurled its circular solar panels.

Its landing sequence complete, InSight will get a few weeks’ rest after its long journey.

But not the scientists and engineers working on the mission.

“Now we start our work,” said Farah Alibay, a payload systems engineer whose job depended on a smooth landing. If one parachute string had become tangled, or one descent thruster failed to fire, the spacecraft may not have recovered, she said. “Every single thing had to go right.”

The science team will have to decide exactly where and when to deploy InSight’s instruments, and they will get started by analyzing details in the first photo, like how the lander’s foot has settled into the lava plain beneath it.

“We’ll be studying that in the next couple of days, looking at the amount of dirt on it, looking at the kind of dust, trying to figure out distribution of particle sizes, all this kind of stuff,” said Bruce Banerdt, InSight’s principal investigator.

After that, Alibay and the rest of the surface operations team will test all their commands on ForeSight, a replica of the lander housed at JPL, before sending them to Mars.

When engineers have ironed out all the kinks, InSight will wake up. Using a robotic arm, the lander will install a super-sensitive seismometer on the Martian surface, where it will listen for meteorite impacts and Marsquakes. The seismic waves from these events will give scientists a clearer picture of the planet’s internal structure.

InSight will then deploy its heat probe, a self-hammering 16-inch nail that will burrow down as deep as 16 feet over the course of several weeks. The instrument will measure how much heat escapes from Mars’ interior, which will reveal the amount of heat-producing radioactive elements it contains and how geologically active the planet is today.

InSight’s radio signals will also be used to track the wobble of Mars’ orbit. This will help researchers understand the size and state of the Martian core.

Together, these experiments will crack open Mars and spill the planetary secrets scientists have sought for decades, said JPL geophysicist Suzanne Smrekar, the deputy principal investigator for the mission.

“I can’t say how satisfying it is to be within a stone’s throw of getting that information about Mars,” she said.

UPDATES:

7:40 p.m.: This story has been updated with additional details about InSight’s landing, news that its solar panels had unfurled, and comments from project manager Tom Hoffman, payload systems engineer Farah Alibay and principal investigator Bruce Banerdt, all of JPL.

12:55 p.m.: This story has been updated with additional information about InSight’s landing sequence and with comments from JPL chief engineer Rob Manning and mission commentator Christine Szalai.

This story was originally published at 11:55 a.m.