Why is Mars so different from Earth? NASA’s InSight mission will dig deep to find answers

Suzanne Smrekar has been trying to take the temperature of Mars for nearly 25 years.

When she first came to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory as a newly minted geophysicist, she started developing tiny robotic probes that would pierce the planet’s surface like bullets and gauge how much heat escaped from its interior.

After five years of work, NASA stowed a pair of the devices on the Mars Polar Lander, which left Earth in 1999. But the spacecraft vanished without a trace just as it prepared to touch down. For days, Smrekar and her teammates listened hopefully for signals, but they heard only silence.

Smrekar was devastated. “We don’t know what went wrong,” she said.

Now she’s getting a second shot. If all goes according to plan, Mars InSight will land safely on a smooth, flat lava plain near the Martian equator on Monday.

Scientists hope the Mars Insight mission will lead to a better understanding of Earth too.

It will carry another version of a geologic thermometer — a 16-inch-long nail that will burrow into the ground — along with a suite of other instruments. Together, they will take the measure of the planet’s vast interior over the course of one Martian year.

Smrekar and her fellow scientists hope that studying the inner workings of Mars will help explain how it formed and then transformed from a warm and potentially habitable world to the frozen, dormant neighbor we know today — in other words, why it has aged so differently than Earth.

InSight’s findings could give scientists clues about what planets need to be capable of supporting life.

“It’s not just about understanding Mars,” said Anne Pommier, a planetary scientist at UC San Diego, who is not involved in the mission. “It will be useful to understand other Earth-like planets.”

::

NASA has long operated a fleet of spacecraft to study Mars from above and a squad of rovers to examine the surface up close.

With InSight, researchers will go deep.

“Understanding the interior of a planet helps us to understand how it formed and evolved, and how the features on the surface came to exist,” said Renee Weber, a member of the InSight science team at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala.

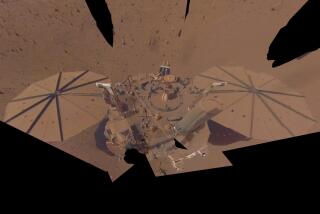

InSight, which stands for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport, will establish a small geophysical laboratory on an alien world. It will measure the heat escaping from inside Mars, listen for seismic waves echoing through its depths, and track the wobble in its rotations.

Once it has landed and engineers at JPL in La Cañada Flintridge have surveyed its surroundings, InSight will install its star instrument: a seismometer.

Almost everything scientists know about the structure of Earth comes from tracking the motion of seismic waves inside it. In 1909, Croatian geophysicist Andrija Mohorovičić postulated that the planet had a crust when he noticed that seismic waves generated by earthquakes sped up as they traveled through the denser rock of the underlying mantle. And in 1936, Danish seismologist Inge Lehmann used a similar approach to determine that a solid inner core lurked inside Earth’s liquid outer core.

Scientists intend to use seismology to construct a detailed picture of Mars’ guts too.

“There are a lot of questions that we have about how Mars’ interior is organized,” says Steven A. Hauck II, a planetary scientist at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland who is not involved with the InSight mission but is eager to see the data it collects. Like Earth, Mars has a crust, mantle and core, but their thickness and composition remain uncertain.

Scientists already know about a few key differences with Earth: Mars is much smaller, and it does not appear to have plate tectonics, so its mantle hasn’t been as stirred up by convection and its crust hasn’t been recycled. As a result, it may offer clues about what planets look like when they first cool and separate into distinct layers.

Researchers almost got answers in the 1970s, when NASA sent seismometers to Mars aboard the Viking missions. But there were problems. The instrument on Viking 1 didn’t survive landing. The one on Viking 2 did, only to reveal the drawbacks of mounting a seismometer on the deck of the lander, a few feet off the ground.

“It never actually recorded what we could definitely say was a marsquake,” the Martian equivalent of an earthquake, Weber said. Instead, it “just recorded the shaking of the lander every time the wind blew.”

This time, InSight will deposit its seismometer directly onto the surface with the help of a crane-like arm. It’s one of the most sensitive instruments ever built, Weber says, capable of detecting even the movements of individual atoms. To keep air from obscuring tiny shivers of ground motion, the whole thing is sealed inside a vacuum chamber; a leak in the enclosure delayed the mission for two years.

InSight’s arm will also cover the seismometer with a protective dome to shield it from the tempestuous Martian weather.

Then, everyone will wait.

Researchers are fairly confident they will record at least a few planetary jitters during the 728-day mission, when meteorites happen to strike. But marsquakes will offer the best chance to map the planet’s interior and will give researchers a sense of how active Mars is today.

::

For the first few weeks, all the seismometer may register is the pounding of InSight’s heat-sensing nail as it hammers itself, bit by bit, into the ground.

Researchers picked the landing site because it has a thick layer of loose soil that the heat probe could drill through, Smrekar said. The location also provides ample sunlight for the lander’s wing-like solar panels.

Ideally, the probe will dig down 16 feet over the course of a month or so. A spring-loaded tungsten weight inside the nail will push it down, pausing frequently to cool off and collect measurements. NASA engineers estimate it could take up to 20,000 hammer strokes to complete the process.

Measuring Mars’ temperature will give scientists clues about the planet’s chemical makeup. The decay of radioactive elements inside Mars stokes its inner fire. So the amount of heat the interior gives off will provide an estimate for how much radioactive material it contains.

Scientists also want to understand how fast Mars is cooling off and where it is in its “life cycle,” Weber said: “Do you have a hot, active planet, or do you have a cold, dead planet?”

Researchers have developed different models for how Mars formed and evolved over time, which they rely on to make inferences about the planet’s past. Getting real measurements of Mars’ heat flux will provide a critical constraint on these models. After all, Smrekar said, “our assumptions may be wrong.”

Clearly, when Mars was younger, its internal heat powered the largest volcanoes in the solar system. In addition to spewing lava, these volcanoes brought water and other gases to the surface, cloaking Mars in a thick atmosphere and perhaps even supplying ancient oceans that could have supported life.

But most of Mars’ atmosphere — and its surface water — disappeared billions of years ago, and InSight’s third major experiment aims to help researchers understand why. That requires looking all the way into the center of the planet.

Like Earth, Mars once had a magnetic field produced by molten metal churning in a liquid core. And like on Earth, the field protected the planet’s atmosphere from the torrent of charged particles streaming off the sun. But Mars’ magnetic field winked out quickly, exposing the Martian atmosphere to the ravages of the solar wind.

“We still don’t know why,” Pommier said.

Perhaps the impact of a giant meteorite snuffed out the circulation in the core. Or maybe its chemistry caused it to stop convecting. InSight will help evaluate these possibilities by sussing out the size and density of the core and determining whether any of it is liquid today.

The principle is simple, said Veronique Dehant, an InSight scientist at the Royal Observatory of Belgium. Imagine spinning a raw egg and a hard-boiled egg on the kitchen counter. “You can tell which one is cooked and which one is not cooked,” she said.

Researchers will track the wobble of Mars’ rotations by monitoring slight changes in the frequency of InSight’s radio signals. Combined with the heat and seismic data InSight will collect, the experiment will give researchers the clearest picture yet of the planet’s heart.

“I’m so excited about this one,” Pommier said.

::

As InSight closes in on Mars, Smrekar said it feels both “thrilling and anxiety-producing.” At long last, scientists will look deep inside another planet.

Of course, as with all space exploration, there is a risk that something could go wrong. But scientists and engineers have learned a lot from earlier Mars missions, and they are not taking any chances.

The InSight team spent years finding the safest possible place for InSight to land, and they have tried to plan for every contingency. Even an ill-placed rock could foil the lander’s experiments.

That’s why engineers have ForeSight, a replica of InSight that lives under Mars-tinted lights at JPL.

After InSight sends home photos of its “workspace,” a team on Earth will shovel the sand on which ForeSight sits to mimic the same slope. They’ll also lug boulders to the same locations as the rocks around its twin. That way they’ll be sure InSight doesn’t make any false moves, Smrekar said.

When InSight’s team has checked and double-checked their commands, the lander will finally get to work deploying its instruments to peer beneath the barren surface of Elysium Planitia. The name refers to the plain of paradise reserved for the dead in Greek mythology.

It’s a fitting place to see just how much life Mars has left.