To visualize the hellishness of the climate crisis in 2021, look no further than General Sherman, the world’s largest tree, wrapped in fire-resistant foil to protect the legendary giant sequoia from flames burning a path of destruction through the Sierra Nevada.

California’s so-called Ancient Ones evolved with fire. It’s crucial to their reproductive cycle. But they aren’t prepared for blazes like those of the last year, which are burning hotter and more intensely as Earth warms, mostly because of the combustion of fossil fuels. Last year, flames killed roughly 10% of the world’s giant sequoias.

The sight of General Sherman wrapped in foil this fall was a cry for help. It was also a sign that the American West has entered a dangerous new era of hotter heat waves, ever-more-brutal droughts and a growing threat of violent extremism on public lands.

There’s still hope for the future. But in a part of the country mythologized for its rugged individualism, going it alone will be a recipe for disaster, climate experts say. States and tribes, big cities and rural towns, liberals and conservatives alike will need to cooperate.

“I am just hopeful that people will recognize that they will live a lot longer if they work together and collaborate,” said Sally Jewell, who led the Interior Department under President Obama and oversaw the management of hundreds of millions of acres of Western lands. “Climate change has the potential to bring people together around a shared concern.”

Record heat. Raging fires. What are the solutions?

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter about climate change, the environment and building a more sustainable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Though climate continued to polarize Washington, D.C. — see the near total lack of Republican support for the clean energy investments proposed by President Biden — there were at least some encouraging signs west of the 100th meridian.

Take the Colorado River and its tributaries, whose waters quench the thirst of tens of millions of people and irrigate millions of acres of farmland from Wyoming to Mexico.

The region has always whipsawed between drought and floods, but now global warming is exacerbating the swings, with an overall drying trend that scientists call aridification. As summer turned to fall, nearly 95% of the American West was saddled with drought conditions. The “bathtub ring” at Lake Mead outside Las Vegas kept growing, showing how much water had vanished from the nation’s largest reservoir.

In August, federal officials declared the first-ever water shortage on the Colorado, triggering cutbacks in Arizona, Nevada and Mexico.

The shortage declaration, while scary-sounding, was the result of a landmark pact in which Southwestern states agreed to forgo some of the water to which they’d otherwise be entitled, in an effort to keep Lake Mead from falling even farther and prompting a true emergency.

From the Capitol riot to vaccines and climate change, a look at what dominated the news and conversation in 2021 as the world began to move past the pandemic.

If the situation worsens, California will accept cutbacks too. John Fleck, a water resources professor at the University of New Mexico, has described the agreement as a model for the future cooperation that will be needed as the Colorado dwindles.

“The river’s future is not all dark,” Fleck and Eric Kuhn wrote. “Innovation, cooperation and an expanded reliance on science are now the foundation for basin-wide solutions.”

There were signs of long-overdue action on the wildfire side of the climate equation too, as the Biden administration raised pay for federal firefighters and worked with California to reduce fire risk by thinning overgrown forests — a stark change in approach from President Trump, who bluntly blamed the Golden State for not “raking” its forests. California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a $15-billion climate package that included money to fight fires, droughts, extreme heat and sea level rise.

Officials also increasingly agreed on the need to set intentional, low-intensity fires — known as “prescribed burns” — of the type that helped protect Lake Tahoe this summer.

But although those solutions could pay dividends over years and decades, the fires keep getting worse.

In California, more than 2.5 million acres went up in smoke by the end of November — fewer than the record 4.2 million that burned in 2020 but still the second-most in modern times. Three people died and more than 3,600 structures were damaged or destroyed.

In California and beyond, some people are deeply in grief, stunned that flames could again imperil some of Earth’s oldest living things.

The smoke from those conflagrations spread far and wide, forcing people to breathe hazardous air up and down the West Coast and as far away as Appalachia. Scientists linked increased smoke exposure with greater susceptibility to COVID-19.

Record temperatures compounded the threat, drying out landscapes and making fires harder to put out. California, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon and Utah endured their hottest summers on record, with the nation as a whole tying the Dust Bowl era for the hottest summer in modern history.

In the Pacific Northwest, a heat wave killed hundreds of people, whose bodies failed them as they roasted in their homes, or on the streets — a dark reminder that heat waves are deadlier than hurricanes and fires, and are only getting more dangerous.

After a village in British Columbia broke Canada’s all-time heat record, hitting 121 degrees, climate scientist Andrew Weaver said the province felt more like Death Valley.

“I’ve been in a lot of hot places in the world, and this was the worst I’ve ever been in,” he said.

The combination of heat, fire and drought wreaked havoc on the electric grid. A blaze in Oregon took down an interstate power line and nearly forced much of California into rolling blackouts. Pacific Gas & Electric and other utility companies sometimes shut off the power intentionally to prevent their infrastructure from igniting fires like the PG&E-sparked blaze that destroyed much of the town of Paradise and killed 85 people in 2018. Utility customers lost power during hot weather as late as Thanksgiving.

California chronically undercounts the death toll from extreme heat, which disproportionately harms the poor, the elderly and others who are vulnerable.

Declining reservoirs, meanwhile, produced less hydroelectricity, which in a cruel twist forced utilities to burn more natural gas, one of the fossil fuels heating the planet.

Federal officials warned that by 2023, there’s a 1 in 3 chance that Lake Powell on the Arizona-Utah border will fall so low that Glen Canyon Dam, one of the region’s largest producers of cheap, zero-emission power, won’t be able to generate electricity at all.

California kept trying to prove that it’s possible to wean society off fossil fuels, although success is far from guaranteed. The state’s 100% clean-energy mandate has a 2045 deadline, a decade later than scientists say is needed worldwide to avoid the worst consequences of climate change. In the meantime, activists say the state isn’t moving fast enough to build solar and wind farms, support the purchase of electric vehicles and reduce oil and gas production.

Even Jared Blumenfeld, who was appointed by Newsom to lead California’s Environmental Protection Agency, acknowledged the state needed to do more, faster.

“Everyone is realizing the front lines of the battle are a hell of a lot closer than we ever imagined. And the threat from the enemy is real and present,” he said.

Though some Western states at least tried to follow California’s lead on climate — Colorado, Oregon and Washington in particular — others followed a different playbook.

Climate change will make it less pleasant to visit public lands in the summer, a new study finds.

In Arizona, regulators backtracked on a plan to require 100% clean energy, only to backtrack again and offer a preliminary sign-off — but with a deadline of 2070, decades beyond what global climate commitments will require. New Mexico’s Democratic governor, Michelle Lujan Grisham, talked a big game on climate but also criticized President Biden for attempting to limit oil and gas production. Wyoming lawmakers kept up a years-long effort to protect the state’s coal, oil and gas companies from economic headwinds.

Then there was Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, who responded to worsening drought by declaring a need for “divine intervention” and asking Utahans to pray for rain.

The same worldview that led some elected officials to dismiss the urgency of the climate crisis fueled a burgeoning movement that protested pandemic-era vaccine mandates, demonized public health officers and sought to wrest control of hundreds of millions of acres of public lands from the federal government.

The desire among many rural Westerners to run cattle, drive ATVs and otherwise do as they please on lands owned by the American public, unimpeded by environmental rules, was hardly a new phenomenon in 2021. But COVID-19 brought new volatility. Prominent “sagebrush rebels” such as Ammon Bundy — who led the armed occupation of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge and whose father, Cliven, sparked an armed standoff with federal officials at Bunkerville, Nev. — used public anger over pandemic restrictions to expand their followings.

Support our journalism

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Subscribe to the Los Angeles Times.

The antigovernment, white nationalist-tinged ideology of Western militias began to spread nationally too, some experts said.

The day after the Jan. 6 insurrection in Washington, D.C., Richard Spotts, a former Bureau of Land Management staffer in Utah, wrote to High Country News that “there is a clear link with the Bunkerville showdown and Malheur Refuge occupation and what happened yesterday at our nation’s Capitol.”

Even without the threat of armed standoffs, treasured Western landscapes faced plenty of challenges from global warming, human visitation and energy development.

Rising demand for sprawling solar and wind farms created new pressure on public lands, forcing the Biden administration to balance the needs of conservation and climate action. More people than ever crowded into many national parks, with 1 million visitors crossing into Yellowstone in July alone; a month later, fire-related forest closures kept Californians out of their beloved Sierra Nevada.

Rising temperatures threatened iconic species, with a federal judge ordering the Biden administration to reconsider its decision not to protect Joshua trees under the Endangered Species Act.

Coastlines weren’t spared, either: The Pacific Ocean kept rising, hastening a reality of vanishing beaches, dangerously eroding cliffs and saltwater intruding on precious groundwater supplies. Nobody wanted to confront the possibility of “managed retreat,” but some communities finally felt they had no choice. Marine heat waves took a deadly toll on ocean ecosystems already stressed by a history of overfishing and pollution.

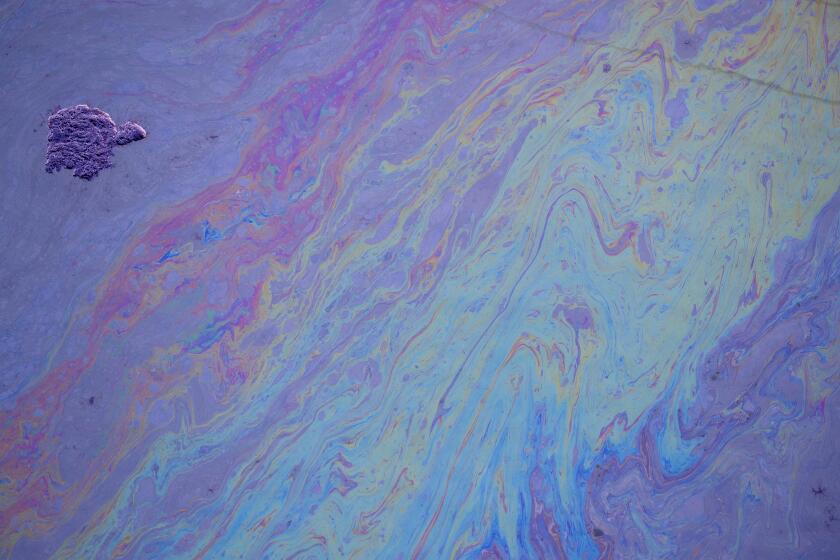

A massive oil spill off the coast of Huntington Beach in October hammered home the reality that fossil fuels don’t just drive the climate crisis, but also pollute California’s water, air and soil, taking a toll on natural ecosystems and human health.

“With or without climate change, the benefits of getting rid of fossil fuels outweigh the costs,” said Drew Shindell, a climate scientist at Duke University.

Even beyond climate change, there are many reasons to transition to solar and wind power — the Huntington Beach oil spill among them.

Environmental activists rallied around the idea of “30 by 30,” a campaign to protect 30% of America’s lands and waters by 2030. The goal is to protect habitat, promote biodiversity, preserve landscapes that keep carbon in the ground and otherwise save some semblance of the natural world as we know it. Biden endorsed the concept.

“Protecting 30 by 30 is not something the U.S. government can do on its own,” Jennifer Rokala, executive director of the Center for Western Priorities, said after the Biden administration announced its “America the Beautiful” initiative. “It will take from-the-ground-up efforts in every state, using many different forms of conservation, to get there.”

Again: Collaboration is key. The last year made that abundantly clear. Whether Westerners can come together to reduce emissions and fortify themselves against the disasters on the horizon is yet to be seen.

In one positive development, firefighters managed to protect General Sherman and other iconic sequoias from this fall’s fires.

But thousands of the giants were still killed by flames. And the climate emergency is just getting started. 2021 will probably go down as one of the coolest years this young century. There’s still plenty of time for the rest of the Ancient Ones to meet their match.

Times reporters Tony Barboza, Anita Chabria, Ian James, Lila Seidman, Hayley Smith, Alex Wigglesworth, Rosanna Xia and former staff writer Anna M. Phillips contributed to this report.

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.