How should California confront the rising sea? These lawmakers have some bold ideas

In a year marked by record-breaking wildfires, extreme heat and unprecedented water shortages, California lawmakers say there’s another — seemingly distant, but just as urgent — climate catastrophe the state cannot afford to ignore: sea level rise.

This oft-overlooked threat is the focus of more than a dozen new bills and resolutions this year — a remarkable political awakening mobilized by years of research and piecemeal efforts across the state to keep the California coast above water.

There’s Senate Bill 1 — the very first measure introduced this legislative session — that confronts sea level rise adaptation head on. Another bill proposes an innovative buyout program that sets the stage for a different, more proactive approach to the difficult choices that have long paralyzed coastal communities from taking necessary action.

These proposals are a paradigm shift in the way officials are now addressing the social, economic and environmental pressures looming over the state’s eroding coastline. Experts say this surge of political interest — and willpower — came not a moment too soon.

There’s a giant gap between what many companies have pledged and what’s actually needed.

Across the state, rising water is already flooding homes. Major roads, utility lines and other critical infrastructure are dangling ever closer to the sea. At least $8 billion in property could be underwater by 2050, with an additional $10 billion at risk during high tides. In just the next decade, the ocean could rise more than half a foot — with heavy storms and cycles of El Niño projected to make things even worse.

Legislative analysts, in an urgent report, recently made the case that any action — or lack of action — within the next 10 years could determine the fate of the California coast. All told, more than $150 billion in property across the state could be at risk of flooding by 2100 if business continues as usual and global temperatures continue to rise.

“The future of California’s coast is in jeopardy … Now is not the time to drown out scientists or put our heads in the sand,” said California Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego), whose extensive measure, SB-1, clarifies legal and bureaucratic obstacles that have often made large-scale planning a nonstarter.

The bill, supported by seven coauthors, also proposes a significant amount of money: $100 million each year for sea level rise adaptation, plus additional funding specifically earmarked for coastal communities that are disproportionately burdened by industrialization and pollution.

A legislative study finds that the next 10 years could determine the fate of the California coast and urges state and local officials to act quickly.

“It’s easy to ignore the problem in front of you until it is a crisis,” Atkins said. “But if we don’t act now, taxpayers, homeowners, businesses, local communities and the state will face massive losses in just a few short years.”

But what exactly this action looks like — and who pays and who benefits — remains a tough balancing act. There are only so many ways to protect critical infrastructure, homes, beaches and entire communities from the rising sea, and each option comes with sacrifices and its own set of controversies.

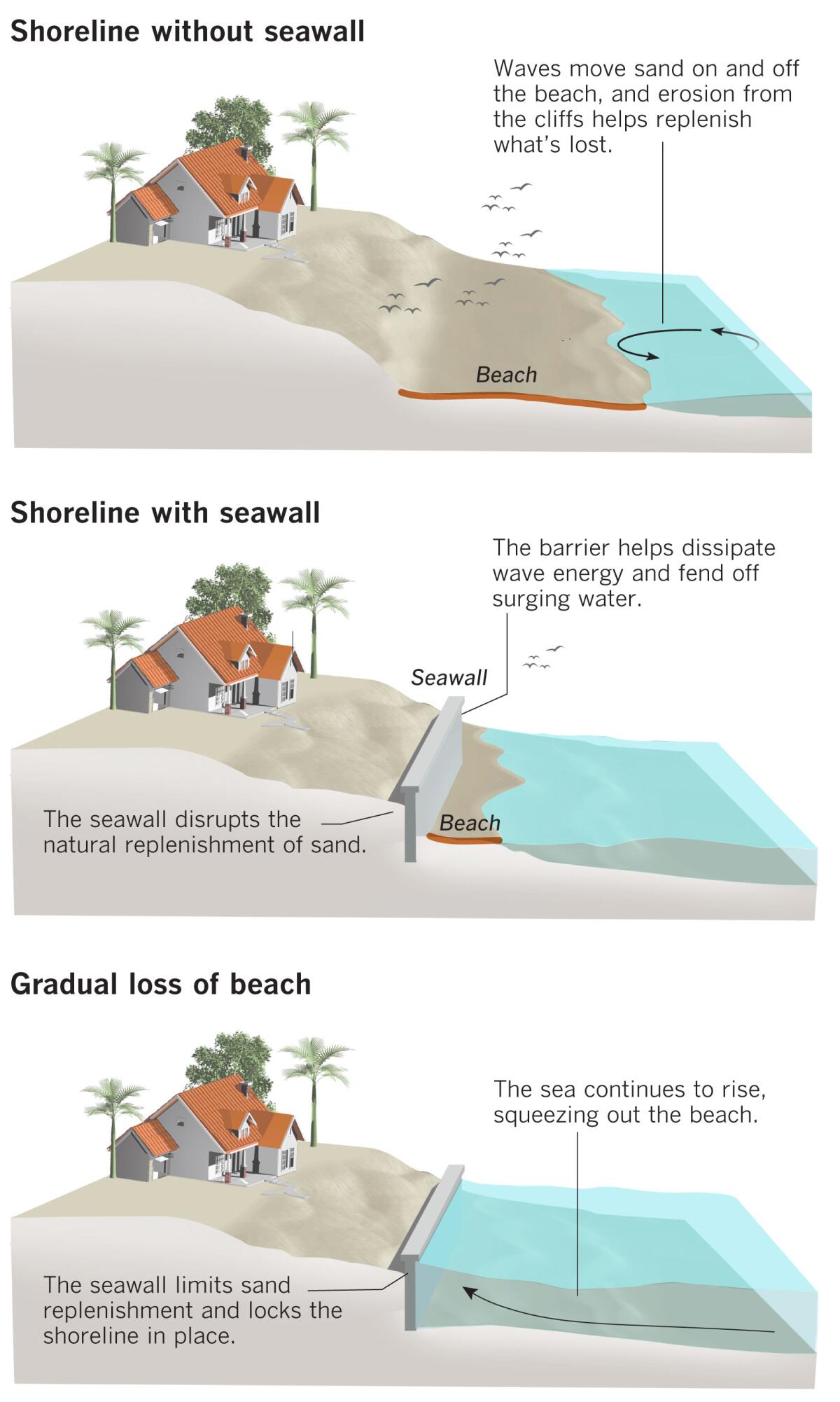

Take seawalls, for example. While effective in protecting beachfront homes and infrastructure in the short term, they disrupt the erosion and natural replenishment of sand — drowning beaches until they narrow or vanish altogether.

Managed retreat — relocating properties and critical infrastructure far enough from the coast to make room for the next few decades of sea level rise — has also been fraught. This option often pencils out as the most cost-effective and forward-thinking — but the logistical challenges of translating short-term interests (preserving property values) into long-term planning (getting out of harm’s way before the water arrives) has been a political quagmire.

One creative idea that has recently emerged is a revolving-loan program introduced by Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica). Senate Bill 83 essentially proposes giving local governments the ability to buy up properties at risk of falling into the ocean in the next decade or two — and then rent them at market value to recoup the costs. When the time comes, the city could then demolish the property and perhaps restore the land as a public park or some form of natural protection from the sea.

This voluntary program would give homeowners the chance to move on their own terms — and sell their beachfront properties while they still have value. Taxpayers, in turn, won’t be burdened with the shocking costs of cleaning up after an emergency. Studies show that society as a whole saves $6 in avoided costs for every $1 spent to acquire or demolish flood-prone buildings before disaster hits.

“We don’t want this to be a net loss to taxpayers. In some cases it could even be a gain… The whole idea of this proposal is: It pays itself off because we’re getting on top of this early,” Allen said. “Think about the cost and lives that could’ve been saved if California had taken more action decades ago to better mitigate against the threat of today’s wildfires.”

Much of this is uncharted. Allen and his staff did not have any case studies to model this program after, so they consulted researchers at UCLA, coastal planners, as well as their colleagues in Sacramento — who helped refine the details of the bill through legislative hearings this year. The proposal so far has received bipartisan support and no registered opposition.

If passed by the full legislature this month, the bill will head to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk for final approval.

Longtime experts in the climate adaptation field have been following these discussions with great interest. This year’s proposals mark a fundamental shift in the oft-held view that responding to sea level rise is a one-time action, rather than an ongoing process that requires bigger-picture planning with the community, said A.R. Siders, who has been studying managed retreat and its equity implications at the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center.

“How do you navigate that middle space where people don’t need to move today, but they will need to move eventually? So many places have been trying to figure out this transition,” Siders said. “That’s where everyone’s struggling — and that’s where I think this lease-back plan is a really interesting one. It has the potential to really help people figure out that middle space.”

Sara Aminzadeh, a commissioner on the California Coastal Commission, said all the legislation this year felt like a major turning point. For the past 10 or so years, the (relatively few) sea level rise bills that have popped up have largely focused on studying the problem, understanding the science and gathering more information to put on a central website.

Now, in addition to the buy-and-rent-back proposal and SB-1, which creates a framework for agencies across the state to work together on more unified goals, other bills this year include measures to improve regional planning, developing an early warning system for coastal landslides, and reducing costly barriers to nature-based adaptation projects. There has also been much discussion with the governor’s office on how to dedicate more of the state budget to building coastal resilience.

“We’re seeing some really significant reforms. … We’re no longer merely trying to wall ourselves against the rising sea, and saying: ‘How long can we stick this out?’” Aminzadeh said. “We’re thinking in a more fundamental way about the things that we care about as Californians — and how to ensure a future in which we still have beaches and coastal parks and access for all.”

Ultimately, the success of any of these proposals depends on the details — and whether they’re implemented in a fair and equitable way.

For Charles Lester, who has been pushing for more substantive sea level rise planning for more than a decade — first as the executive director of the Coastal Commission, and now as director of UC Santa Barbara’s Ocean and Coastal Policy Center — these increasingly focused discussions have been encouraging.

“The legislation shows that we understand that adaptation will cost a lot, but that it is an important investment that society needs to make,” he said, noting that many costs — and priorities on where to invest this new infusion of funding — still need to be worked out.

This is just the beginning, he said, “of what will be a huge undertaking for many decades to come.”