A former power broker attempts a defiant comeback in Mexico

Reporting from Mexico City — The most powerful woman in Mexico was known simply as “The Teacher.” She was a kingmaker, a confidant of presidents and a devotee of $5,000 Hermes purses, jaunts in private jets, plastic surgery and retreats to her luxurious villas in California.

Elba Esther Gordillo’s over-the-top lifestyle and political maneuverings as head of the nation’s largest teachers union eventually turned her into an icon of corruption and resulted in federal charges of corruption and money-laundering.

Jailed in 2013, she spent five years in custody as the government sought to prove that she had illegally diverted union funds for personal use. This month, a federal judge dismissed the charges, ruling that the union had approved her expenditures and that prosecutors had obtained bank account information without the necessary judicial order.

The Mexican attorney general’s office said it “respected” the judge’s decision, but denied any wrongdoing in its ultimately failed prosecution.

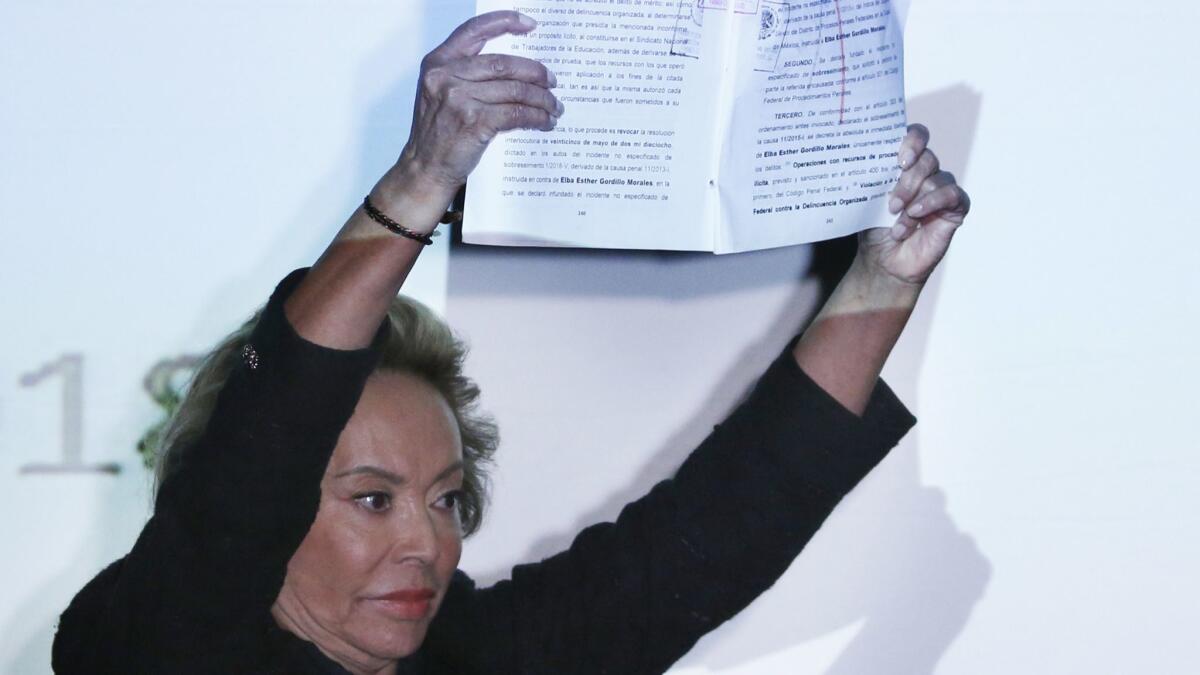

Now a defiant Gordillo is mounting a very public comeback.

She gave an unrepentant news conference here this week, insisting she was a “scapegoat,” a victim of “political persecution” and a noble advocate for the nation’s much-maligned teachers.

“I hope that this moment marks the future of my life, of my yearnings and my hopes,” she said Monday in a televised address.

Gordillo, 73, offered no apologies, no explanations for her amassed wealth, no admission that she had done anything wrong. She took no questions from the press. This was not a mea culpa session.

Rather, she presented her ordeal as a metaphor for a nation that had gone tragically amiss, but was somehow now on its way back, a saga of persecution and vindication.

“The long term of imprisonment was also a difficult and profound learning period,” she said. “Without doubt I changed, we all changed. The country changed.”

Gordillo seemed to be positioning herself both for a union comeback and as an agent of the anti-establishment backlash that swept Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador to victory last month in the presidential election.

“The world and our country are immersed in a profound transformation and we have received a great lesson from the citizens,” she proclaimed, echoing the leftist president-elect.

Commentators immediately mocked what they viewed as the self-righteous, even delusional, discourse from a fallen potentate who had been accused of embezzling some $160 million in union funds — and who has yet to account for her extravagant spending habits during the nearly quarter-century she headed the National Union of Education Workers.

Prosecutors alleged that Gordillo siphoned union funds for almost $3 million in Neiman Marcus purchases, $17,000 in plastic surgery and multimillion-dollar homes outside San Diego. Gordillo always denied any wrongdoing and said her riches came from an inheritance from a grandfather and “sweat,” alluding to her hard work.

Despite the dismissal of charges against her, many seem unconvinced of Gordillo’s probity.

“While Elba Esther presents herself today as a new champion of the anti-establishment, the reality is that she personifies perverse unionism and corruption of the system,” the columnist Leo Zuckermann wrote in the Excelsior newspaper.

Gordillo was a product of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, which ruled Mexico for much of the 20th century through a patronage network. Most unions were close allies that reliably delivered votes on election days. Gordillo also served as a party deputy and senator in the federal legislature.

In the 2006 presidential election, however, Gordillo shifted her allegiance — and that of her followers — to Felipe Calderon, the candidate of the opposition, center-right National Action Party. Her support helped Calderon achieve a narrow victory.

Today, the chances that Gordillo will return to power seem slim. Union delegates elect the leader of the 1.6-million-member teachers union, and Gordillo still has considerable grass-roots backing. But Mexico’s president traditionally wields considerable influence in the decision.

During a meeting with President Enrique Peña Nieto on Monday, Lopez Obrador, who has vowed to eradicate the country’s deep-rooted corruption, said he had no intention of recruiting the ousted union boss.

“The teacher Elba Esther will not work in the next government,” he said.

Peña Nieto rejected Gordillo’s contention that she was a victim of political persecution.

“Nothing is more false than that,” Peña Nieto said.

Her arrest in 2013 was viewed by many in part as an attempt by the Peña Nieto administration to break the union stranglehold on public education and impose a sweeping reform agenda. Mexico’s public education system is regularly ranked among the worst in the hemisphere.

But the president’s planned reforms stalled amid fierce resistance from teachers opposed to new testing standards for instructors. Lopez Obrador has vowed to embark on a new education overhaul.

“We are going to construct a consensus with teachers and parents,” he said Monday.

At the Mexico City hotel where Gordillo made her comeback address, supporters of the former union leader rallied to show solidarity. But, outside, some dissenters lofted banners saying she should be sent back to jail.

One placard read: “My kids could eat for a year for the cost of one of your pairs of shoes.”

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

Twitter: @PmcdonnellLAT

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.