Federal probe of 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre says ‘no avenue’ for criminal case in connection to attack

OKLAHOMA CITY — The first-ever U.S. Justice Department review of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre concluded that although federal prosecution may have been possible a century ago there is no longer an avenue to bring a criminal case more than 100 years after one of the worst racial attacks in U.S. history.

The Department of Justice said at the outset of its probe that it had no expectation anyone would be prosecuted, but in a more than 120-page report released Friday, federal investigators outlined the scope and impact of the massacre — an attack by a white mob on a thriving Black district that left as many as 300 people dead and 1,200 homes, businesses, schools and churches destroyed.

“Now, the perpetrators are long dead, statutes of limitations for all civil rights charges expired decades ago, and there are no viable avenues for further investigation,” the report states.

Among the findings in the Justice Department investigation were federal reports from just days after the massacre, in 1921, conducted by an agent with the precursor agency to the FBI. But today’s investigators said they found no evidence that any federal prosecutors ever evaluated those reports.

A black-owned Oklahoma newspaper would not let the state forget the day white mobs murdered hundreds of African Americans in Tulsa.

“It may be that federal prosecutors considered filing charges and, after consideration, did not do so for reasons that would be understandable if we had a record of the decision,” the report concluded, adding that if the department didn’t seriously consider such charges, “then its failure to do so is disappointing.”

The report also examined the role of various people and organizations in the massacre, including the Tulsa Police Department, local sheriff, Oklahoma National Guard and then-Tulsa Mayor T.D. Evans, determining that each played a role in the chaos and destruction, either by failing to act or by actively participating in the attack.

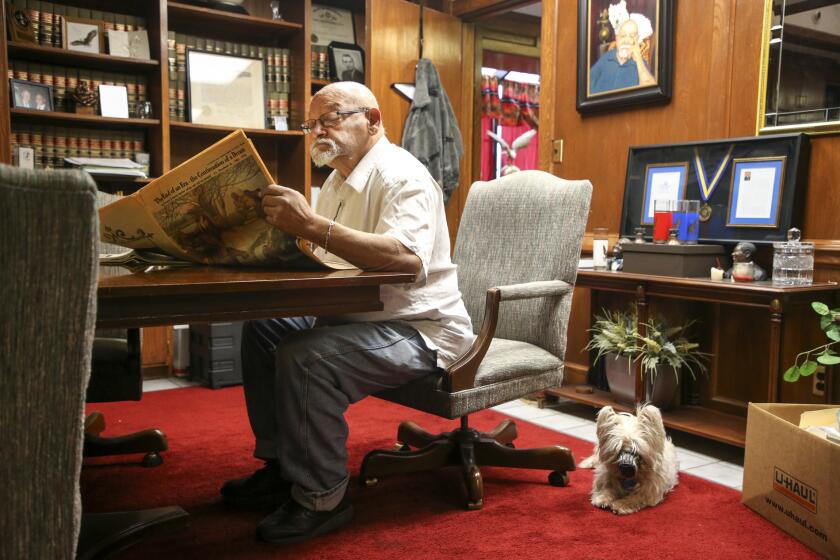

Damario Solomon-Simmons, an attorney for the last known survivors of the massacre, Viola Fletcher and Lessie Benningfield Randle, both of whom are 110, did not respond to a request for comment on the report. Solomon-Simmons had previously decribed the DOJ’s decision to investigate the massacre as a “joyous occasion.”

The mayor of Tulsa, Okla., says a World War I veteran is the first person identified from graves filled with victims of the 1921 Tulsa massacre of the city’s Black community.

Victor Luckerson, a Black author and historian who wrote a book about Tulsa’s Greenwood district, said there is value in the government establishing a definitive record of the attack.

“Having government documents available lays the groundwork for the possibility of reparations,” Luckerson said. “Any of those discussions about reparations, one of the first questions is how we establish a factual record of what happened.”

A researcher working for a state commission in 1999 estimated the damage from the attack to be $1.8 million in 1921 dollars, a figure the report said would be about $32.2 million today.

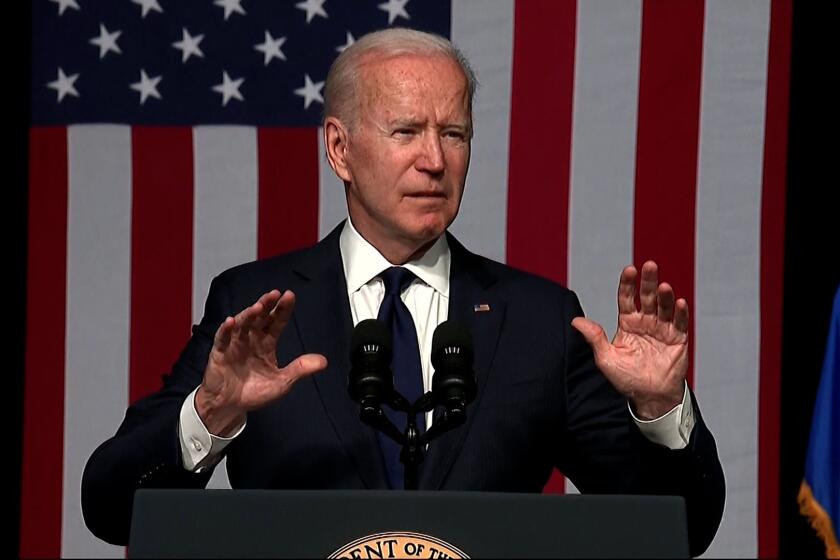

Biden marks the 100th anniversary of the massacre that wiped out a thriving Black community in Tulsa.

The Oklahoma Supreme Court in June dismissed a lawsuit by survivors, dampening the hope of advocates for racial justice that the city would make financial amends for the attack.

The nine-member court upheld the decision made by a district court judge in Tulsa last year, ruling that the plaintiff’s grievances about the destruction of the Greenwood district, although legitimate, did not fall within the scope of the state’s public nuisance statute.

Murphy writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.