Tiny ethnic Armenian enclave may spark a wider conflict

It’s an old conflict, with some dangerous new twists.

Fierce fighting has flared this week between Armenia and Azerbaijan, neighboring ex-Soviet republics in the southern Caucasus region, a key energy corridor that sits at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, Russia and the Middle East.

The focus of the conflict is Nagorno-Karabakh, a tiny mountainous enclave that is recognized internationally as part of Azerbaijan, but whose population of about 150,000 is majority ethnic Armenian.

If fighting that erupted Sunday escalates into all-out war, it could potentially drag in big regional powers — Turkey, a U.S. ally in the North Atlantic Treat Organization that has strong ethnic, cultural and linguistic ties to Azerbaijan; and Russia, which is friendly with both countries, but has a defense alliance with Armenia, as well as a military base there.

On Tuesday, Armenia and Azerbaijan traded angry accusations as well as intensifying artillery fire along their border. In what would mark a significant escalation, Armenia said one of its warplanes was shot down Tuesday by a Turkish F-16 that took off from Azerbaijani territory. Both Turkey and Azerbaijan issued heated denials of responsibility for any downed Armenian warplane.

The latest fighting, which has killed scores and wounded hundreds, has prompted outside calls for conciliation. But diplomatic efforts have so far been sluggish, which some analysts blame in part on preoccupation with the coronavirus crisis.

“Since the advent of COVID-19, there has been a lack of proactive international mediation,” said Olesya Vartanyan, a senior South Caucasus analyst for the International Crisis Group. “No shuttle diplomacy, no calls to the leadership in Baku and Yerevan” — the respective capitals of Azerbaijan and Armenia.

Here is a look at the roots of the long-running conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, and why it holds the potential to become a wider threat.

Turbulent history

In the rugged pocket of territory — historically inhabited by both Christian Armenians and smaller numbers of Muslim Turks — resistance to Azerbaijani rule goes back decades.

In the Soviet era, Nagorno-Karabakh gained autonomous status, but its struggle to break away from Azerbaijan outright began even before the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. Fighting from 1988 onward killed about 30,000 people and displaced 1 million. That battle ended with a 1994 cease-fire and de facto self-rule.

But no country, not even Armenia, recognizes it as an independent republic, although Armenia and the Armenian diaspora provide it with financial support. Violent flare-ups have occurred periodically, including in 2016, when clashes left at least 200 people dead, and in July and August.

Not surprisingly, the two sides do not even agree on what to call the thickly forested 1,700-square-mile area, which is only about 1½ times the size of Yosemite National Park. Ethnic Armenians use an ancient name for the region, Artsakh. The widely recognized name of Nagorno-Karabakh is a compound of the Russian word for “mountainous,” and the Russianized version of an Azeri word meaning “black garden.”

Strategic significance

The struggle over Nagorno-Karabakh is seen as a potentially destabilizing element in the strategic South Caucasus region, long a fault line between empires. Azerbaijan, via pipelines to Turkey, supplies about 5% of Europe’s gas and oil, and any escalation in fighting could imperil that flow.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict could also accentuate regional rivalry between Russia and Turkey, which have competed for influence in an array of volatile venues, including Syria and Libya.

Turkey’s role

Turkey held large-scale military exercises with Azerbaijan in July and August, and has vocally taken its ally’s side in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The two share a common enmity with Armenia, whose relations with Turkey are shadowed by the Armenian genocide that claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people beginning in 1915 under the Ottoman Empire, a precursor to the modern republic of Turkey. The Turkish government disputes that a genocide took place.

Domestic political considerations also color Turkey’s current stance. Long-ruling President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has seen a significant erosion of popular support in advance of 2023 elections, and “whenever this has happened in the past, he uses foreign policy to mobilize his nationalist base,” said Gonul Tol, director of the Middle East Institute’s Turkey program. “Now we’re seeing that in Nagorno-Karabakh.”

Turkey repeated Tuesday that it would stand with “brotherly” Azerbaijan, but has avoided saying whether it is providing drones, warplanes and military experts, as Armenia claims. Azerbaijan denies receiving such aid.

Armenia’s change of leadership in its 2018 revolution raised hopes that tensions over Nagorno-Karabakh might ease, but those prospects have since dimmed. Even before this flare-up, Armenia’s prime minister, Nikol Pashinian, has taken what Turkey views as an unyielding position on the enclave’s future.

The Armenian diaspora

The worldwide Armenian diaspora is far larger numerically than Armenia’s actual population of about 3 million. One of the world’s largest concentrations is in Southern California, and the community has watched the latest escalation in and around the enclave with dismay and alarm.

On Tuesday, the Armenian National Committee of America’s western region called in a statement for Azerbaijan to be held accountable for “egregious violations of fundamental human rights” and “perpetration of war crimes against civilian populations.”

Mediation efforts

Russia, France and the United States have worked in the past to calm outbreaks of trouble in Nagorno-Karabakh, but this time, no coordinated effort has so far emerged.

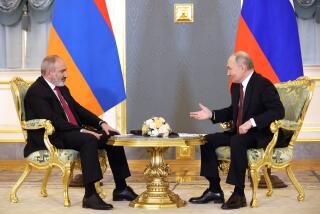

Russian President Vladimir Putin, uneasily eyeing a popular uprising in the former Soviet republic of Belarus and weathering international condemnation over the poisoning of dissident Alexei Navalny, may be motivated to seek to play the role of statesman. He has repeatedly called for calm, most recently in a conversation Tuesday with Armenia’s leader. But with his long-held ambitions to burnish Russia’s great-power image, Putin may also want to avoid seeming to accede to Turkey’s wishes.

In the United States, a heated presidential campaign spares little attention for a conflict with which many Americans are unfamiliar, but Democratic contender Joe Biden on Tuesday urged the Trump administration to call on leaders of both Azerbaijan and Armenia to immediately de-escalate. He also said Washington must demand that “others — like Turkey — stay out of this conflict.”

Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo, traveling in Greece, on Tuesday called for a halt to hostilities. President Trump’s wording on the matter, however, has been more vague; he said this week the conflict was being looked at “very strongly.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.