‘I see a monarch! Oh my God!’: The joy (and importance) of counting butterflies

Editor’s note: The Wild is all about featuring a variety of exciting voices from SoCal’s outdoors scene. For the next several weeks, that voice will belong to Times staff writer Lila Seidman. A native Angeleno who joined the Times in 2020, she’s investigated mental health policy and jumped on breaking news, and is excited to write about the outdoors in her home state. She loves trail running in the mountains near her Tujunga home and revels in the continuous realization that Los Angeles always has more to offer.

In the frigid air of first light, an eager brigade clutching binoculars descended on a public park in a tony enclave near Pacific Palisades.

Conspicuous clothing choices hinted at their purpose. One man’s open jacket revealed a bright orange-and-yellow butterfly — the color nearly identical to his dyed hair. Real laminated Lepidoptera wings dangled from a woman’s ears.

The roughly 20 volunteers journeyed to Santa Monica’s Rustic Canyon Park to learn the art of counting Western monarch butterflies, which hunker down for months along the Pacific Coast as they complete their migratory cycle.

It’s a serious — and surprisingly involved — practice.

You are reading The Wild newsletter

Sign up to get expert tips on the best of Southern California's beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains in your inbox every Thursday

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Annual tallying of the Dorito-hued monarchs from Mendocino to Baja California — on the coast as well as in some inland areas — provides insight into the butterflies’ population size.

“In order for this data to be actually useful then there needs to be a certain amount of rigor,” said 44-year-old Thea Wang, a first-time volunteer who attended the recent training. (The Glendale resident has some experience in fieldwork; she earned a doctorate in ecology and evolutionary biology from UCLA and studied social behavior in marmots in California’s White Mountains.)

Why all the effort to count monarchs?

The Western Monarch Count, which officially began in 1997, is powered by an increasing number of citizen scientists who are directed to visually scour trees at the crack of dawn and take detailed notes. Organized by the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, a pair of major counts are conducted around Thanksgiving and the New Year.

Given dramatic shifts in the population in recent years, the data seems particularly critical. Western monarch numbers plummeted in the winter of 2020-2021, when less than 2,000 of the striking pollinators were counted across all of their overwintering haunts — a gasp-worthy drop from the roughly 20,000 fluttering around a few years prior. Fears of extinction piqued. Then, surprisingly, they rebounded. In the past two years, their ranks have climbed to nearly 300,000, prompting cautious hope, as my colleague Jeanette Marantos recently reported.

But the bigger picture is unsettling: Monarch populations in the West have dropped more than more than 95% since the 1980s, when it’s estimated they numbered in the millions, according to research by Xerces Society conservation biologist Emma Pelton and others.

Last year‘s count drew the most volunteers to date, with 250 people fanning out to 272 overwintering sites.

Those who attended the recent sunrise training spoke of a strong desire to do their part in preserving natural ecosystems threatened by climate change. Many referred to a personal connection to dazzling monarchs. Several, like Wang, have a science background they felt could be leveraged for a worthy cause.

A combination of factors motivated Lorraine Dubois, 68, to trek from Encino to the brisk park, but she said it boiled down to “essentially a lifelong addiction to monarchs.”

“I feel like it’s somebody coming from another life telling me that they’re around,” Dubois told me in a grove of eucalyptus trees — beloved by monarchs.

So you want to join a count ...

Joining a monarch count is not something you can just roll out of bed and join. (Even if your alarm is set to 5 a.m., like mine was the morning of last weekend’s training.) It’s a process that requires significant planning and keen observation skills.

First, it requires advance registration. (The cutoff was Nov. 1.)

Then, aspiring butterfly talliers must connect with a regional coordinator, who will help come up with a monitoring plan for the overwintering season, including important counts held from November through January.

When I met the volunteers, they were on the third step — receiving hands-on training.

A day before the training, I received an email from Xerces Society’s Sara Cuadra, a conservation biologist, reminding volunteers to watch a series of training videos — 72 minutes’ worth in all.

There was a packing list that included binoculars, water and note cards. A plant identification app and weather measuring device known as a kestrel were optional. Preparation also includes downloading an app to enter data collected in the field (unless a volunteer opts to use paper forms).

Cuadra and volunteer Zach Zito led the training. It’s helpful, they said, to be able to spot trees the pollinators prefer to overwinter in, such as eucalyptus, pine, cypress, sycamore and redwood. Surveyors then must methodically scan the tree from various angles.

It’s hard not to register vibrant monarchs when they’re flitting in the air. But it’s nearly impossible to count them in that state. Volunteers are instructed to hunt for butterflies early in the morning when temperatures are low and the chilled-down monarchs tend to huddle together on branches with closed wings. It’s easier to count static monarchs, but they’re harder to see.

Volunteers don’t just count; they’re asked to log a variety of details to flush out the scene. Three or more monarchs are recorded as a cluster. But there are also loners, sunners (wings open), fliers, grounders (alive on the ground) and dead monarchs.

(When a tree is dripping with monarchs, making it difficult to count them individually, observers are advised to count a cluster and then multiply the figure by the estimated number of clusters on the tree.)

Other data fields include air temperature and weather conditions, type and coordinates of trees and observed potential threats and disturbances. There is even an option to upload photos.

Once volunteers confirmed what site they’d be monitoring, Zito recommended scouting it out ahead of time to familiarize themselves and get a sense of where to look. He recalled wandering around a Venice golf course for more than two hours, before finally spotting 600 monarchs nestled in a tree.

Some of the sites are on private property or are otherwise inaccessible. Volunteers are asked to respect restrictions. Even in public areas, someone squinting through binoculars at the crack of dawn at seemingly empty trees can throw off passersby. Some are intrigued, others are angered.

The golfers, for example, “weren’t happy with me,” Zito said.

A sighting — exciting

After orientation, the amateur naturalists periodically directed their binocular-enhanced gaze to the trees, which a nearby placard noted were planted in the 1880s by Venice developer Abbot Kinney.

They weren’t expecting to see much. Southern California is not known for the large swarms of butterflies that can be observed overwintering further north along the Central Coast, including Pismo Beach, Pacific Grove and Santa Cruz.

Cuadra said seeing butterflies in the park we’d gathered in was historically “hit or miss.” Surveyors counted only one last year — and just one the year before that.

Most volunteers had already left when Wang shouted, “I see a monarch! Oh my God!”

At first, I saw nothing in the blur of branches. Then, guided by Wang, my eyes locked on the brilliant orange triangle. Its wings were open, drinking in the rising sun. Using my binoculars, I observed the distinct black-and-white markings on its wings that make it look like stained glass.

After a few minutes, I averted my gaze for a moment. When I turned back, the insect was gone.

It was a hopeful sign. And excellent data.

3 things to do

1. If you can’t count ‘em, watch ‘em. If you missed the cutoff for this year’s monarch count, or you’re not sure you’re cut out to be an amateur naturalist, you can still delight in gazing at the butterflies as they overwinter along the California coast. Monarchs typically arrive in November and stay through February, peaking between Thanksgiving and Christmas. Anecdotal reports suggest hearty numbers this year, a tentative cause for hope amid their sobering decline.

These are spots known for hosting epic overwintering monarch gatherings:

- Monarch Butterfly Grove at Pismo State Beach

- Monarch Sanctuary in Pacific Grove

- Natural Bridges State Beach in Santa Cruz

- Fiscalini Ranch Preserve in Cambria

- Coronado Butterfly Preserve in Goleta

- Ellwood Mesa Open Space in Goleta

Mark Woodward, an avid amateur photographer who lives in the Santa Cruz area, observed “the greatest numbers I’ve ever seen” at Lighthouse Field State Beach, a lesser-known overwintering spot. The day before Halloween, Woodward — known as Native Santa Cruz on social media — spied half a dozen branches on a pine tree that were “completely covered” with monarchs.

“I was excited, happy. It’s great news to see them in those numbers,” said Woodward, who posts ample photos of the monarchs and fellow local wildlife celebs, Otter 841 and her new pup. A detailed map of monarch overwintering sites can be viewed at westernmonarchcount.org.

2. See the hottest place on earth at its lushest. As my colleague Christopher Reynolds vividly details in a recent story, Death Valley underwent an unusual transformation following a fierce summer rainstorm. Typically bone-dry, the vast national park east of Los Angeles is dotted with puddles and teeming with “confused” wildflowers. But it’s not clear how long the surprising sight will last.

Those hoping to catch a glimpse can plan a day trip or try to nab a campsite reservation. Or, if you’re looking for something a little different, check out the scenery on a jeep tour. Pink Jeep Tours — aptly conducted in pink vehicles — resumed its Death Valley tours on Nov. 1 after a hiatus due to flooding. The roughly 10-hour tour, which departs from Las Vegas, hits popular sights in the area, including Dante’s View, Artist’s Palette and Badwater Basin, which currently boasts a lake. Tickets are $284 for adults and $256 for children. pinkadventuretours.com

3. Swoon for swans. Free, naturalist-led swan tours kicked off this month near Marysville in Yuba County. Located about 45 minutes north of Sacramento, the area is home to one of the largest populations of overwintering tundra swans in the Central Valley, as well as an abundance of other avians — including geese, ducks, raptors and shorebirds. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife offers the roughly two-hour tours through flooded rice fields to watch and learn about the birds on select Saturdays from November through early January. Remaining tours will be held on Nov. 18, 25; Dec. 2, 9, 16, 30; and Jan. 6. Attendees must pre-register by sending an email to [email protected]. More information at wildlife.ca.gov.

The must-read

A chance encounter with a doctor experienced in guiding blind runners changed the direction — and speed — of Eline Øidvin‘s life. Øidvin, who was born almost completely blind, gave up her athletic dreams as a kid after trying and failing to keep up with peers. But a first fateful run morphed into her meteoric rise as a marathon runner.

The Korea-born, Norway-raised athlete has outpaced most of her visually impaired competition in 47 marathons, including winning her division in the celebrated Boston Marathon. More recently, Øidvin turned to mountaineering after hearing her trusted marathon guide gush about high peaks of the Sierra Nevada.

My fellow Times reporter Jack Dolan didn’t just chronicle her ascent of towering Mt. Langley, he joined the 14,000-foot climb as one of her guides. Øidvin, Dolan writes, is one of a growing number of adventurers who refuse to let their disabilities hold them back from rugged feats.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

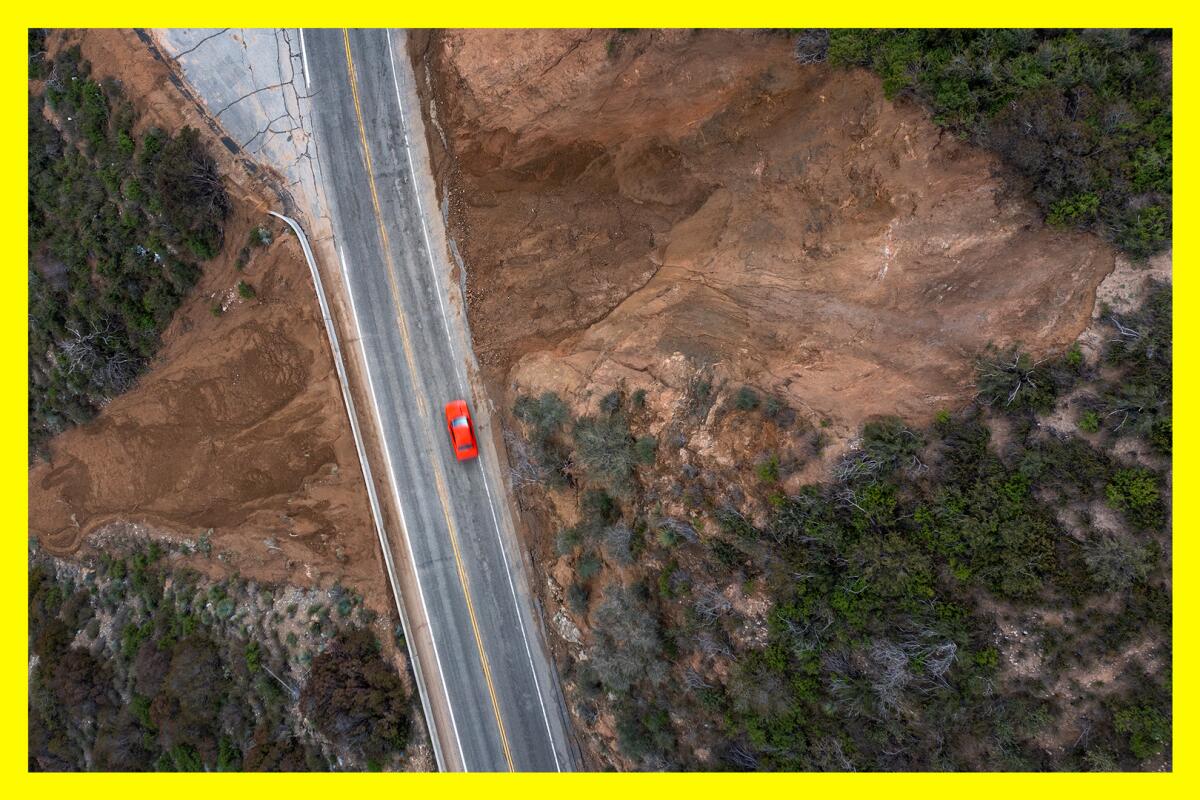

After a months-long closure due to winter storm damage, a nearly 21-mile stretch of the Angeles Crest Highway is open again, restoring public access to recreation spots in the high country of the forest, my colleague Grace Toohey reports.

The recently repaired road runs from Upper Big Tujunga Canyon to Islip Saddle. Now that it’s operational, visitors can check out trails, picnic areas, lookout points and the Chilao Visitor Center that were off limits for eight long months.

Other sections are still shuttered as they undergo repairs, including an area beginning at Red Box junction. There is a detour to bypass that closure but another one spans from north of Islip Saddle to Vincent Gulch — scuttling direct access to the mountain town of Wrightwood.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.