How becoming a geology nerd gave me a new appreciation of the outdoors

Editor’s note: The Wild is all about featuring a variety of exciting voices from SoCal’s outdoors scene. For the next several weeks, we’re featuring a series of guest writers (whom we’ve dubbed “wilders” ) from around The Times who are eager to share their adventures with you. This week’s guest wilder is The Times’ science and medicine reporter Corinne Purtill. When she isn’t digging around in the dirt for work, she enjoys running on the beach, paddling in search of sea lions and chasing after the various small mammals she lives with.

For a very long time, I was bored by rocks. Dismissive of stones. I used “geology” when reaching for an example of the most tedious subject I could think of; I used phrases like “dull as rocks” without concern.

I’d pull over to admire Earth’s biggest hits, like Sedona’s fiery sandstone or the Grand Canyon’s layer cake of history. Otherwise geology seemed to me the sour gray aunt of science, a pastime for people put off by the charm and character of actual living things.

Then, one day last year, a package arrived from a friend in the U.K. I cut through a thick layer of Mick Jagger stamps and out slid a copy of Helen Gordon’s “Notes From Deep Time: A Journey Through Our Past and Future World.”

I read Gordon’s book. Then I read all four volumes in John McPhee’s masterpiece “Annals of the Former World.” And then I became a geology nerd, and my world has been better for it ever since.

To clarify: I do not own a rock hammer or a boring tool. I can’t tell the difference between limestone and shale. But now, when I am hiking, driving or futzing around through landscapes both new and familiar, I think about what McPhee described as “The Picture.”

The Picture is a space-eye view of our planet that takes in the whole of its 4.5-billion-year history. It’s a moving picture, one in which continents form, disperse and form again, in which landscapes endure for millions of years and then erode forever.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

This giant rock we live on is in constant, ceaseless motion, making and remaking itself through the magical combination of infinitesimal movement and incomprehensible amounts of time.

The rocks at the top of Mt. Everest were once at the bottom of the sea. Canyons, islands and mountain ranges formed and wore away before even our earliest ancestors were around to see them. The chunks of earth that make up today’s continents have joined and scattered so many times that the borders we draw upon them seem almost sweetly naive, like the moats children dig in the sand to defend their castles from the tide.

No matter how awe-inspiring, any natural feature is here but for a blip of time, its geographic coordinates “a temporary description,” as McPhee put it, “as if for a boat on the sea.” To take in The Picture is to appreciate that every single physical thing that Earth or man creates will eventually be subsumed by this force of relentless motion and regeneration.

Plant-based mind-expansion attempts have never gone well for me: My brain gets itchy, my skin feels tight, pets start looking at me in contemptuous and unsettling ways. But contemplating deep time does the job without the side effects.

Geology is one of those interests that can go big or small. Real rockhounds know the chemical components of their favorite minerals and the geological conditions that created them. I am sort of a tectonic dilettante, thinking broadly about the long-ago shifts that created a landscape but fuzzy on the specifics of granite versus gneiss, or Pliocene versus Pleistocene.

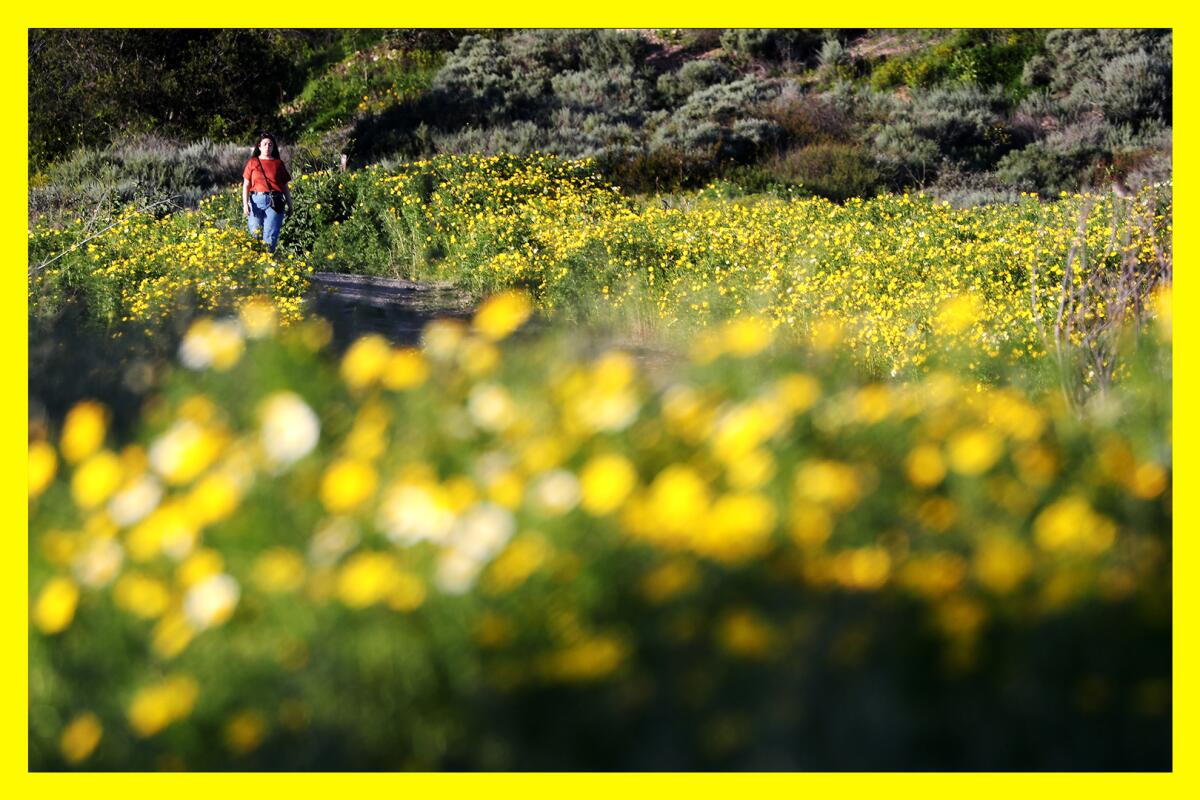

I still pay attention to the wildlife and plants along a hiking path, but if I come across a large, imposing wall of rock, as I did in Eaton Canyon a few weeks ago, I will also pause to admire it. I’ll ponder how many millenniums it’s been there or the seismic event that sheared it from something bigger.

If I’m headed on a long car trip, I will Google not just good places to eat but also if there are any interesting formations visible from the road. My brother and I took all our kids to Nevada last month, and in Cajon Junction, Calif., I called out to the kids as we drove past the Mormon Rocks.

“Look at those rocks!” I said as the sandstone boulders whizzed past. “They’re 20 million years old!”

Did they care even a little? No. They did not. That’s OK. They had their own ways of passing the time. But looking for those rocks added another layer to the journey for me, accentuating a landscape whose nuances I might have missed.

The deep past of our planet also gives me a sense of peace when I think about its future. Climate and ecological trends are, to put it mildly, not very encouraging. I have doubts about our long-term success as a species, and deep concern for those unlucky enough to share this epoch with us.

But I have immense faith in this planet. Yes, we may witness in our lifetimes the collapse of the ecological systems on which every current living thing depend. Huge bummer. But this rock — this magical, irrepressible little space rock — will remain. It will slough us off, and get on with the business of making itself anew.

So try it next time you are out and about, either in the splendor of nature or just bopping around town. Do a quick search online for the ancient history of the landscape, of the story of how any particular place happened to take its current shape.

Think about the things that lived on the planet at the time the rocks were forming, how many epochs have come and gone since, what the world might look like when it all inevitably wears away. Then marvel at the happy accident that placed this view and you together, two temporary wonders crossing paths in time.

3 things to do

1. Pitch in for public lands. Sept. 23 is National Public Lands Day, the largest single-day volunteer event for the country’s parks, preserves and refuges. If you’re in the mood to travel, the National Park Service has cleanups and service projects at Point Reyes National Seashore, Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Redwood National and State parks. Closer to home, the Palos Verdes Peninsula Land Conservancy is celebrating the day with a volunteer cleanup at the Native Plant Demonstration Garden at White Point Nature Preserve in San Pedro, from 9 a.m. to noon on Sept. 23. No experience needed; you’ll pull invasive weeds, water native plants and groom trails while looking out over the Pacific. Don’t leave without popping by the native plant sale at the garden that goes from 10:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. Sign up at pvplc.org.

2. Connect with your prehistoric past at Dino Fest. A must-do for families with dinosaur fans at home, this annual event features talks and hands-on workshops from the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum’s paleontologists, many of whom are fresh off the summer fossil digging season. Once you’re there, don’t miss the museum’s new “L.A. Underwater” exhibition. The land that is now California spent most of the dinosaur era submerged in a shallow sea, and the display is a fascinating look at our once-aquatic world. The lanky carnivore Coelophysis is the featured dinosaur at this year’s festival, which runs 9:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Sept. 24. Dino Fest is included in the price of an admission ticket, and is free for museum members. Tickets and additional information are at nhm.org.

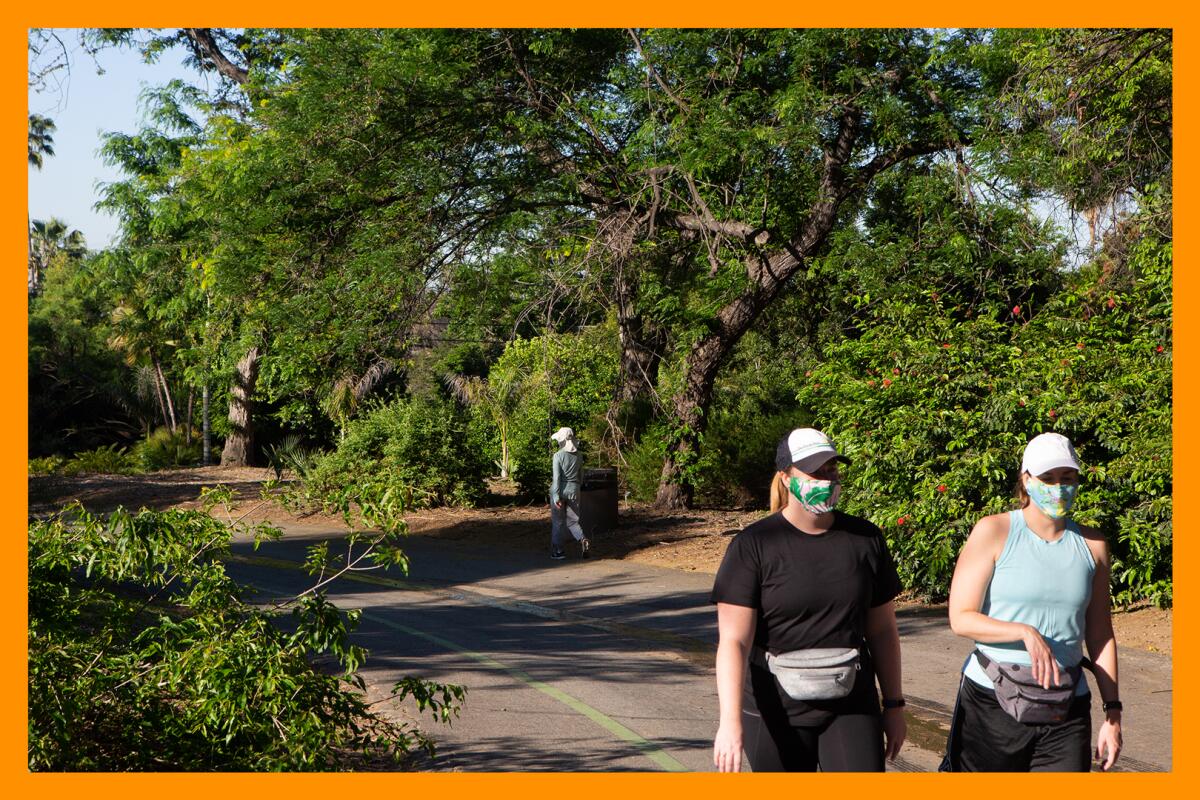

3. Cleanse yourself in a forest bath. In the Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, practitioners immerse themselves in nature slowly and mindfully, as a way of reconnecting both with the natural world and with one’s own senses. If you’re curious, the L.A. County Arboretum and Botanic Garden is hosting guided forest baths inspired by shinrin-yoku during the full moon. The walks this month are from 6:30 to 8:30 p.m. on Sept. 29 and 30. Advanced registration is required. Tickets are $25 for arboretum members and $35 for the general public. See more at arboretum.org.

The must-read

A few weeks after I joined the Los Angeles Times in April 2022, an article caught my eye about a woman on a personal quest to walk every street and marked trail of Santa Cruz County. The story was as full of unexpectedly wondrous discoveries as the walks themselves, rendered in prose that made my breath catch in my throat.

“She noticed spiraling vines of wild cucumber dripping down fences and how they would bounce back like a spring if she pulled them,” read one sentence.

“Her goal had been to take a photo of something beautiful on every street,” read another. “But her idea of what could be beautiful was upended.”

The author of those lovely phrases, former Times staff writer Diana Marcum, passed away Aug. 9 due to complications from a brain tumor.

Marcum lived in the Central Valley and earned a Pulitzer Prize in 2015 for a series of narrative portraits of farmworkers. She had a gift for noticing unforgettable details, and for beckoning readers over to marvel at what she’d found, in language as naturally beautiful as the world it described.

Marcum’s 11-year archive at The Times, where she worked until December, is full of treasures. I will always be partial to the aforementioned tale of the woman who found herself by hiking, but you may find a gem of your own. Virtually all of them are a reminder of how much beauty and heartbreak crunches beneath our footsteps, and what an astonishing gift it is to be here, now.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

I’ve been spending a lot of time for work lately at the Mt. Wilson Observatory, home to some of the greatest scientific discoveries of the 20th century. Lately, the grounds have also played host to some incredible cultural experiences. The Mt. Wilson Institute hosts regular concerts in the vaulted dome of the famed 100-inch telescope — the acoustics are incredible — and later this month, L.A.’s acclaimed experimental opera company the Industry will use the space to present “Star Choir,” an “interstellar chamber opera.”

The drive alone is worth the trip: The observatory is reached via a winding journey up the Angeles Crest Highway, with several spots to stop and take in sweeping vistas along the way. (My fellow car sickness sufferers: Brace yourselves.) Once at the top, take in the breathtaking view of Los Angeles while waiting for the performance to begin and wander the grounds of an observatory that was, for a while, the most important place in the universe to discover the stars.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.