‘Like an F-14 in cleats.’ Bo Jackson instantly wowed the Raiders with his athleticism

On Oct. 15, 1987, 11 days after wrapping up his rookie season with the Kansas City Royals, Bo Jackson was scheduled to fly to Southern California and check in with his new team. There wasn’t a new team to check in with. Beginning on September 22, the NFLPA (National Football League Players Association) announced it would strike over the right to free agency, as well as better benefits and the end of Astroturf surfaces. That resulted in a canceled third week of the season, followed by three weeks of games featuring “fake” replacement players on the field and “real” self-exiled players marching in the stadium parking lots while gripping kill the scabs signs. “I was one of those sign holders,” said Trey Junkin, a Raider tight end, “looking like an asshole.” Jackson made clear that he would not play until the legit Raiders were back in uniform, then watched as many of those legit Raiders — including star defensive linemen Howie Long and Bill Pickel — tucked their tails between their legs and crossed the picket line.

The strike finally ended after 24 days, and on Oct. 17 Jackson — renting an apartment in nearby Redondo Beach — caught a ride to the facility with James Lofton, the veteran wide receiver. When Jackson stepped from Lofton’s vehicle, he was spotted by Jerry Robinson, a veteran linebacker.

“Hey, Bo,” he said. “I knew you were here.”

“How?” Jackson replied.

“Because,” Robinson said, “the Brinks truck is parked out front.”

Jackson walked through the front doors at 332 Center Street in El Segundo, passed a physical examination and earned his $500,000 reporting bonus. “To anyone who cares,” he announced with a grin, “I just made my first half mil!” He found his locker, where a JACKSON 34 nameplate lorded from above and a JACKSON 34 white jersey dangled off a hanger.

To help its 28 franchises adjust to the post-replacement world, the NFL announced rosters could (temporarily) contain as many as eighty-five players — forty beyond the norm. So in a seeing-your-grandma-naked level of awkwardness, the Raiders locker room was overflowing with four distinct categories of Homo sapiens:

1. Men like Chetti Carr (defensive back — Northwestern Oklahoma) and David Hardy (kicker — Texas A&M), who spent three weeks recapturing past gridiron glories but would soon return to their lives as plumbers, truck drivers and accountants.

2. Men like Long, Pickel and offensive lineman Bruce Wilkerson — who crossed the line to the dismay of their teammates and would have to face the consequences.

3. Men like cornerback Mike Haynes and quarterback Jim Plunkett — who dismissed those who returned early to work as one would a scurrying cockroach. “Howie was one of my best friends,” said Mitch Willis, a Raiders defensive lineman. “But that didn’t sit well with everyone. So when it was over, and we all had to sit in the locker room together — the air was thick.”

4. Bo Jackson.

Angel first baseman J.T. Snow casually gazed across the room, and gasped.

Los Angeles (which went 1-2 in replacement action) would continue its season with an Oct. 25 home game against the Seahawks. Al Davis, the owner, requested a good number of the scabs to stick around to help scrimmage against the back-again Raiders and reacclimate the men to combat. That’s why, on that first day, some initially failed to notice Bo Jackson in their midst. There were too many unfamiliar faces in too many unfamiliar jerseys.

Head coach Tom Flores spoke to the players for about fifteen minutes (“I’m not asking you all to like one another. But I am asking you to be professionals”), then had them take the field, stretch and begin some drills.

Two of the veteran Raiders, linebackers Matt Millen and Rod Martin, could not have been more excited. Both detested the strike and, in particular, the scabs. So when replacement running backs grabbed handoffs, Millen and Martin transformed into starving wolves staring down wounded squirrels.

One halfback took a toss.

POW!

Another halfback ran a sweep.

BAM!

A fullback tried plowing up the middle.

THUD!

“We were just drilling these guys,” said Millen. “For sport.”

Joe Scannella, the offensive backfield coach, sent a different running back onto the field.

“Let’s go!” Millen yelled. “Bring it!”

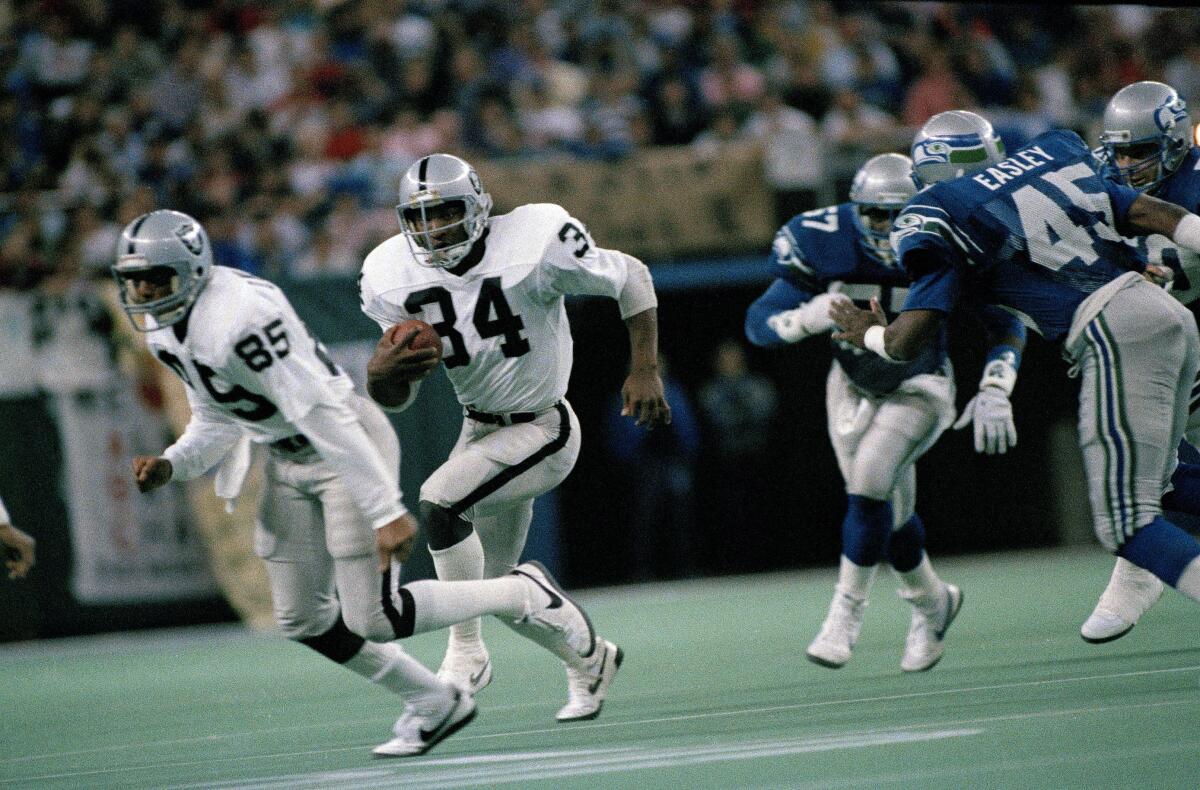

The different running back took a pitch from quarterback Vince Evans. Millen had the ideal angle on him — “everyone could see I was about to make the hit,” he recalled. “And I’m just about ready to explode into him. Then the guy hits a gear ...”

Millen reached out his arms, but the different running back motored past and into the secondary. When Millen returned to the huddle, he apologized.

“That’s on me,” he said. “I don’t know what happened.”

“You’re just rusty,” Martin said.

The offensive and defensive units lined up for another play. This time, the different running back took a pitch and ran in the other direction. Once more, Millen closed in, extended — and missed. “Again, he hit another gear,”

Millen recalled. “Some scab running back is making me look like a fool.”

Back in the huddle, Millen was mortified. “Guys, I’m so sorry,” he said. “I can’t touch that freakin’ scab. I don’t know what’s wrong with me.”

From beneath his silver helmet, Martin was guffawing.

“What’s so funny?” Millen asked.

Martin laughed and laughed and laughed.

“You dumbass,” he said. “That ain’t no scab. That’s Bo Jackson.”

“Oh, thank God,” Millen said. “Thank friggin’ God.”

Watching from a few feet away, Lofton looked at Marcus Allen, the team’s star halfback. “Well,” he said, “there goes your job.”

Lofton was joking — sort of.

Jeff Pearlman’s book on the Showtime era Lakers is the basis of a TV series on HBO, but the show “Winning Time” follows a different path from the book.

“When you play football long enough, you get used to norms,” said Steve Strachan, a Raiders running back. “There are higher norms and lower norms, but everything is in a range. But when Bo came onto the field that first day, we were all seeing something we’d never witnessed before. We were seeing a different paradigm of an athlete. Someone that big moving in ways we’d never seen anyone else move.”

Much like the Royals, many of the Raiders had taken offense to Jackson’s “hobby” dismissal of their sport. Football was the world of broken arms and broken legs. One either played through pain or found himself on the next flight out. The NFL was certainly no hobby.

Besides the newness of it all, the other complication was the Raiders already had a star Heisman Trophy–winning halfback on the roster. Now entering his sixth season, Allen was on the short list of NFL’s elite ball carriers, right there with the Rams’ Eric Dickerson and San Francisco’s Roger Craig. He was an artistic runner whose sleek, slithery moves made him a darling of the NFL Films highlight reels. Yet even as Allen won the Super Bowl XVIII MVP award in 1984 and ran for a league-best 1,759 yards in 1985, Al Davis never took to him. There are 73,103 conspiracy theories, ranging from Allen once fumbling twice in a big game against Kansas City to Allen’s pretty features and Hollywood tendencies to Allen (not Davis) appearing on the cover of the Lou Sahadi book “Domination: The Story of the 1983 World Champion Los Angeles Raiders.”

The bottom line: jealousy.

“If you asked, ‘Who’s the face of the Miami Dolphins?’ — it would be Dan Marino,” said a longtime Raider executive who requested anonymity. “‘Who’s the face of the Dallas Cowboys?’ Tony Dorsett or Troy Aikman. Go through every NFL team, and there will be a player or two or three who symbolize everything. Lawrence Taylor with the Giants. Jim Kelly with the Bills, Joe Namath with the Jets. Now do the Raiders. There is no one — and that’s by design. For Al, no one was ever going to be bigger than the emblem, the patch on the eye, the symbolism. Al would never allow a player to overshadow the team — or Al. And Marcus was coming far too close.”

Davis could have traded the twenty-seven-year-old Allen to any team in the league, and received quality in return. For all his good attributes (an unquenching thirst to win, a love of the fans, a lifetime of charitable endeavors), however, the Raiders owner possessed a raw cruelty that bordered on barbarism. Davis had built up a foaming-from-the-mouth resentment of Marcus Allen — and he sure as hell wasn’t going to present him with the gift of a fresh start. “Al wanted America to forget who Marcus Allen was,” said Terry Robiskie, an assistant coach. “That was how you punished a star for being too big a star.”

In Jackson, Davis acquired an unwitting anti-Marcus participant. He wanted to see Allen crumble; wanted to watch the pain as Allen sat on the bench, his world reduced to meaningless carries toward the end of blowouts.

“Marcus was a great running back,” said Flores. “But when Bo hit the practice field, the whole team went, ‘Wow!’”

This was exactly what Al Davis hoped for.

Allen was thrilled by neither Bo Jackson’s presence nor $864,000 salary for an abridged season (compared to Allen’s $900,000 contract for a full year). But he was mature enough to recognize Jackson meant no harm. They were two members of the Heisman club being paid exorbitant mounds of dollars to play a child’s game. And, not for nothing, Jackson was reasonably likable. He didn’t come in demanding attention. He listened when Allen spoke, never interrupted, asked good questions. There was a surprising innocence to the man — why, roughly 30 minutes before the first practice was scheduled to end, Jackson was spotted eyeing the door to the locker room.

“Bo! Are you OK?” yelled George Anderson, the head trainer.

“Bo’s tired,” Jackson replied. “Bo’s gonna take a shower.”

Robiskie interrupted to explain that Flores wanted to go over some passing routes.

“Oh, oh — OK,” Jackson said. “Bo will stick around.”

“Nobody took offense,” said Bruce Davis, an offensive lineman. “It was kind of endearing.”

Jackson’s goal was to suit up for the Oct. 25 Seattle game. Toward the end of one practice, the coaches asked Jackson to be timed in the 40. The field was a bit wet from a recent rain shower, and some mud was peeking through the grass. Jackson — still wearing a helmet and pads — lined up on one end, and Flores and two assistants stood with stopwatches alongside a designated finish line.

Q & A with Bo Jackson, Mr. Know-It-All

Someone yelled GO! — and Jackson ran —“like an F-14 in cleats,” said Long. He crossed the line, and the coaches compared their times.

“I’ve got 4.19,” said Flores.

The other two nodded — same and same.

Richard Romanski was the Raiders equipment manager. Flores told Jackson to run again, but demanded Romanski stand by the line and make certain Bo wasn’t cheating.

GO!

“I’ve got ... ” said Flores.

“What?” asked Romanski.

“No,” said Flores. “This isn’t right.”

“What?” Romanski replied.

“I’ve got a ... 4.17,” Flores said.

The other coaches nodded — same and same.

Barely breathing hard, Jackson tapped Joe Madro, the team’s personnel consultant, on the arm. “Bo is finished for the day,” he said, and retreated to the locker room.

Jackson stripped out of his uniform and walked toward the shower. Sitting nearby were three hulking linemen — Davis (6-foot-6, 287 pounds), Charley Hannah (6-foot-5, 260 pounds) and Sean Jones (6-foot-7, 280 pounds) — and they watched in awe as their new teammate, naked from head to toe, sat on the floor and churned out 250 sit-ups and 250 pushups.

Hannah looked at Jackson, then stared down at his own gut. “Can’t believe we’re both men,” he said. “Just look at him.”

Flores told the team’s beat writers that Jackson playing against Seattle was unrealistic. This didn’t sit well with the newcomer. In his mind, unrealistic was unrealistic. Following his third practice, he informed Long that if he weren’t activated for the Seahawks, he’d quit. “Those SOBs didn’t get me here to sit on the bench,” Jackson said. “If I’m not playing, I’m gone.”

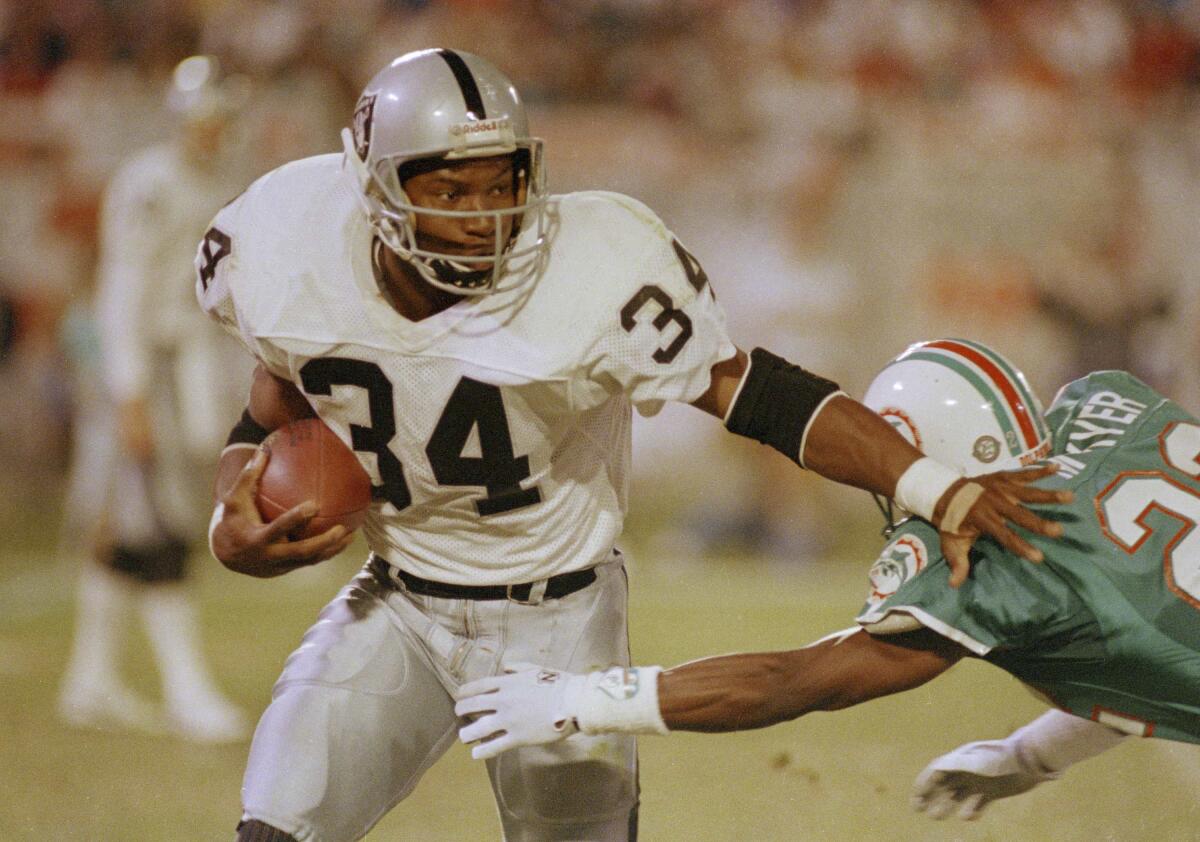

On the morning of Oct. 25, the headline JACKSON TO MAKE DEBUT FOR RAIDERS appeared in the Santa Maria Times, and readers learned that Flores did, in fact, include the running back on the forty-five-man roster.

The kickoff was scheduled for 1 p.m. at the Los Angeles Coliseum, and Jackson arrived three hours early to begin his new journey. His locker was situated alongside the other running backs, and Jackson dressed as he had at Auburn. Shoulder pads just so, knee pads just so. Elbow pads, double wrist bands. He slipped on his pants, then his black jersey with the silver number 34. He grabbed his helmet, walked onto the field for warm-ups, stretched, did some drills. ...

And that was about it.

Seattle cakewalked to a 35–13 triumph, and Jackson never played. Flores later explained that once the Seahawks jumped out to the enormous advantage, there was no real use for the newcomer and his unfamiliarity with the playbook.

When asked afterward about his day, an irritated Jackson snarled “I’ve got nothing to say” before walking off.

Worst of all, the blowout served as a glorious NFL showcase not for Bo Jackson, but for Brian Bosworth, Seattle’s brash rookie linebacker out of Oklahoma. Bosworth was 22 and rich (a 10-year, $11 million contract) and either (depending on viewpoint) a superhero or super villain.

He wore his hair in a ridiculous bleach-blond, side-shaved quasi-hawk and had his ears pierced. He walked with an irritating strut unbecoming of one with such limited experience. In the advance for the game, Bo vs. Boz was a heavy talking point. It was the saga of two larger-than-large phenoms with big dough and big egos, and Bosworth showed little respect for his fellow newcomer. “Bo,” he said, “has to prove himself.”

Afterward, Bosworth admitted he was disappointed Jackson was kept out. “But,” he insisted, “we’ll meet again. I’m sure of it.”

Excerpted from the book THE LAST FOLK HERO by Jeff Pearlman. Copyright © 2022 by Jeff Pearlman. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.