In the post-pandemic world the United States is struggling to bring forth, how many people are we willing to let die of COVID-19 each year?

Yep, let’s go there.

Should your vaccinated grandmother’s death from COVID-19 be considered an acceptable loss? Should seasonal spikes in casualties among the unvaccinated elicit more than a shrug? Should life go on without disruption if a new coronavirus variant starts killing as many youngsters as childhood cancers?

You won’t see politicians calling news conferences to acknowledge that some deaths are inevitable and some lives aren’t worth what it would cost to save them.

The Path From Pandemic

This is the second in an occasional series of stories about the transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic and how life in the U.S. will be changed in its wake.

But acceptable numbers of deaths are the common currency of public health professionals. And they are a central factor in every debate over when — and after what expenditure of money and effort — the time has come to move on.

Declaring an end to the pandemic is about deciding how much illness, death and disruption is “accepted and acceptable as a part of normal life,” said Erica Charters, a historian with Oxford University’s “How Epidemics End” project.

Setting an upper bound on the number of COVID-19 deaths the country will tolerate each year is the basis for decisions about when it will be OK to drop pandemic safety rules, and when it might be necessary to reinstate them.

If the U.S. public health emergency ends, Americans would be vulnerable to a new coronavirus variant that sparks another COVID-19 surge.

A growing number of Americans have concluded the time to move on from the pandemic is now. In mid-March, 64% of adults who took an Axios-Ipsos poll said they’re in favor of lifting all federal, state and local COVID-19 restrictions — up from 44% in early February.

That sentiment isn’t necessarily reckless. This week’s average daily death rate is just over a third of what it was a month ago, and has declined more than 75% since Omicron deaths peaked in early February. Essentially all of the coronavirus cases in circulation here are versions of the Omicron variant, which causes milder disease than the strains that preceded it. Plus, at least 95% of Americans have some immunity to the virus as a result of vaccination, past infection or both, according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Implicit in a decision to drop the last remaining safety rules is a willingness to abide the current mortality rate. Over the last week, COVID-19 has claimed an average of 626 lives in the U.S. each day. That’s fewer than the roughly 1,900 who die of heart disease and the 1,650 who die of cancer each day, on average, but well above the 147 lost to influenza and pneumonia combined.

For public health experts, the calculus is more explicit. Mortality and morbidity — the words their profession uses for death and illness — are on one side of the equation, and tools like seat belts, blood pressure medication, smoking-cessation programs and vaccines are on the other.

Those tools vary in cost, intrusiveness and political acceptability. Despite public health campaigns and legal mandates, Americans continue to drive drunk and leave seat belts unfastened. Tobacco kills more than 480,000 people a year in the United States, yet 34.2 million adults continue to smoke. Diabetes claims more than 100,000 lives a year, but efforts to discourage the sale and consumption of sugary drinks — a significant contributor — have met fierce resistance.

At some point, all efforts to limit preventable deaths will hit the hard wall of funding constraints, medication availability and people’s willingness to take steps to protect themselves and others. That’s where the number of deaths that is “acceptable” comes into focus.

“We really need a national consensus on what the acceptable number of deaths is” for COVID-19, said Michael Osterholm, who directs the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy.

Southern California recorded the highest coronavirus case and COVID-19 death rates of any region in the state throughout the winter surge, a Times analysis found.

No matter what steps the country takes, there’s no way for that number to be zero.

Unlike vaccines for diseases such as measles, polio and diphtheria, the ones available now for COVID-19 don’t produce lifelong immunity. Nor does a past infection, even a really bad one. And considering that the coronavirus has established itself in animals including ferrets and white-tailed deer, the threat of resurgence will always be with us, Osterholm and two colleagues explained in a recent edition of the Journal of the American Medical Assn.

The CDC and other federal agencies are still deciding on the criteria they’ll use to determine when the pandemic has ended. There’s still time — Dr. Rochelle Walensky, the agency’s director, said late last month that we’re not there yet.

So far, the CDC’s advice on loosening COVID-19 restrictions has focused on local, not national, conditions. The key indicator is the capacity of a county’s hospitals to handle a new influx of patients.

A group of 23 prominent public health experts from across the country has made more progress. In their “Roadmap for Living with COVID,” specialists in immunology, virology, healthcare economics and public health detail a litany of conditions that will need to be met to usher the United States safely into a post-pandemic era.

In that “next normal,” the “Roadmap” explains, the coronavirus remains very much with us — an endemic virus that continues to circulate, sicken and kill, but at levels well below those of the last two years.

The experts propose that the country treat COVID-19 as one among a cluster of respiratory viruses — including influenza, respiratory syncytial virus and other pathogens — that wreak a predictable level of havoc year in and year out. Hospitals are prepared to contend with these annual onslaughts of illness, and Americans have accepted the amount of sickness and death they cause as normal.

One indication of our complacency: Even in a bad influenza season, close to half of American adults do not get a flu shot.

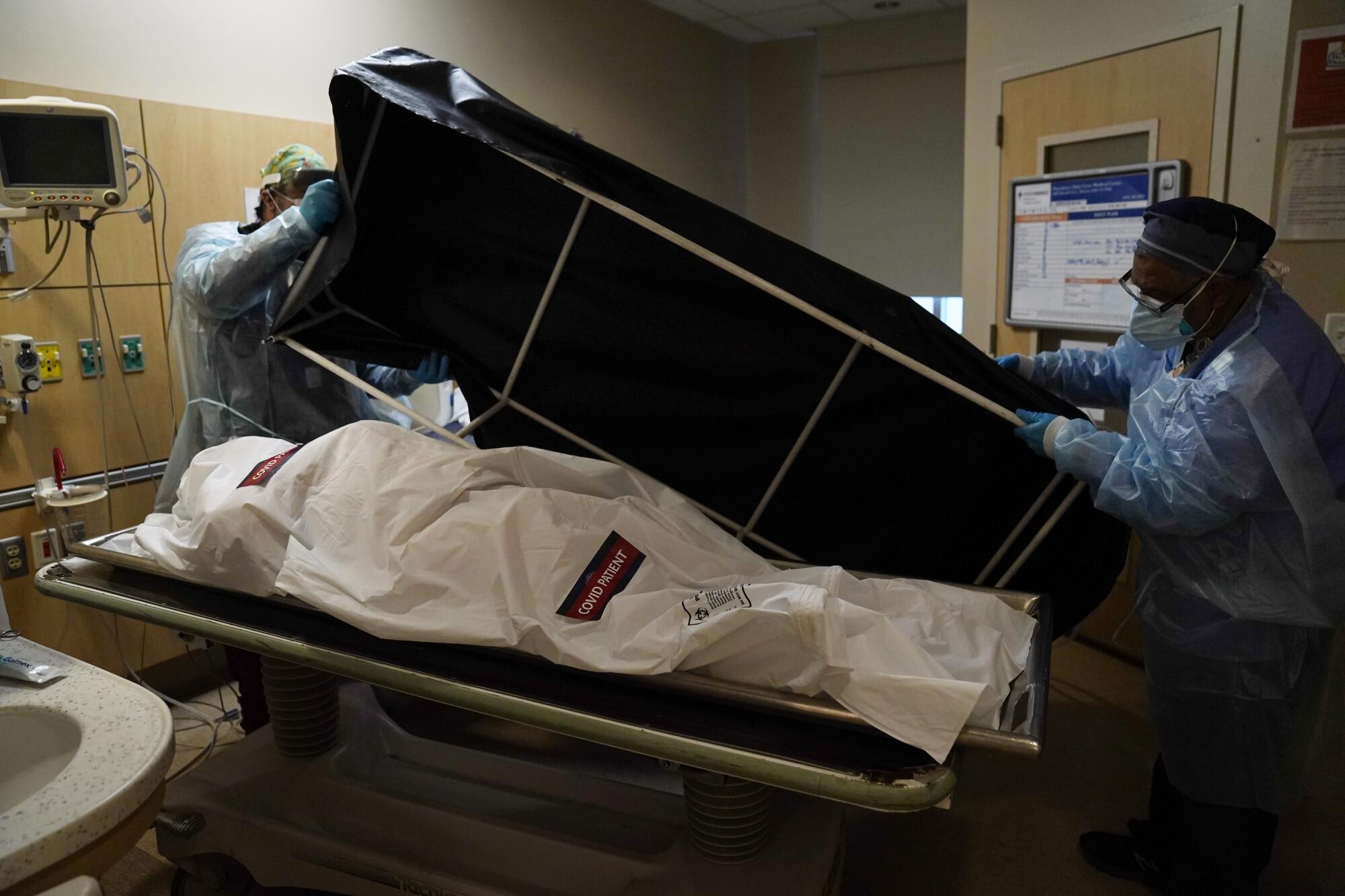

The man collecting the Loma Linda hospital’s COVID victims was all but invisible

Hospitals can usually manage the influx of patients with respiratory diseases without compromising the care of people with cancer, heart disease or other life-threatening conditions. Nor do they defer or cancel the routine care that keeps the patients with an array of illnesses from getting sicker.

With that in mind, the “Roadmap” authors came right out with a suggested number of acceptable yearly deaths from COVID-19 and other respiratory illnesses combined: 60,225.

That figure works out to 1 death per 2 million Americans, or 165 per day nationwide. Add them all up and you have the rough equivalent of an extremely severe season of influenza.

“There was no magic to it at all,” said Osterholm, who contributed to the “Roadmap.” “Our goal was to say that at these numbers and below, you’re much less likely to be stressing the healthcare system.”

That’s important because “deaths increase when hospitals cannot provide optimal care,” the authors wrote. An overwhelming influx of patients with respiratory illnesses can result in fatalities from all kinds of diseases.

It also matters who dies, said Jeffrey Kahn, director of the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University. When deaths are concentrated among a stigmatized minority, as they were when the HIV/AIDS epidemic struck, the world was slower to respond. On the other hand, when children are the principal victims, as with polio in the 1950s, the nation was united in its determination to stop the spread.

“It very much matters which slice of the population is most affected by this or other infectious diseases,” Kahn said.

Similarly, when opioid overdose deaths began to exact a heavy toll on white people in the 1990s, the public health response came more quickly than with other kinds of drug deaths that fell heavily on Black Americans.

Remember all those problems we had with vaccine equity? Now they’re cropping up with new COVID-19 medications that are in short supply.

But that may be changing, Kahn said. The pandemic’s disproportionate toll on communities of color has drawn attention to long-standing racial and ethnic disparities in health and prompted concerted campaigns to address them.

In addition to counting deaths, an ideal “dashboard” of the nation’s post-pandemic well-being would account for how much of the population has immunity to circulating respiratory diseases, and how much virus is detected in wastewater. If those indicators get too high, they would trigger “circuit breakers” such as a renewed mask mandate and limits on social gatherings, the authors wrote.

These circuit breakers reflect a basic principle of ethical decision-making in democracies, said Kahn, who was not involved in the “Roadmap.” Once people have the information and tools they need to protect themselves from harm, they should be free to go about their business without the interference of public health strictures.

However, it’s reasonable to place limits on those freedoms when their exercise injures too many people, including vaccinated grandmothers and at least a smattering of children.

“That’s the push-pull of public health,” Kahn said.