As the coronavirus releases its deadly grip on the United States and pandemic rules governing daily life fall away, is it time to declare the national public health emergency over?

More than one-third of Americans think so, polls show. So do dozens of Republican members of Congress who have called on President Biden to “unwind” the emergency declaration “so our country can get back to normal.”

After two years that saw nearly 80 million infections in the U.S. and almost 1 million COVID-19 deaths, the desire to move on is understandable. But experts warn that ending the health emergency now would leave Americans in a vulnerable position if a new variant sparks another surge and officials lack the legal authority to respond.

It would also terminate the Food and Drug Administration’s power to fast-track authorization of COVID-19 vaccines, tests and treatments. Plus, it would deprive many Americans of perks they’ve come to take for granted, including the ability to get those items free of charge.

The Path From Pandemic

This is the first in an occasional series of stories about the transition out of the COVID-19 pandemic and how life in the U.S. will be changed in its wake.

“People have been wishing for back to normal, but you should be careful what you wish for,” said Georgetown University’s Lawrence Gostin, an expert in public health law. “This’ll be a whole new world.”

The public health emergency was first declared by then-Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar on Jan. 31, 2020. It has been renewed every 90 days since to preserve a sweeping array of measures used by Washington and the states to fight the pandemic. It will be up for consideration again on April 15.

The emergency declaration is the primary legal pillar of the U.S. pandemic response. Even with new infections and deaths in steep decline, Biden hinted in his State of the Union speech that he wasn’t quite ready to let it go.

“We never will just accept living with COVID-19; we’ll continue to combat the virus as we do other diseases,” the president said. “And because this virus mutates and spreads, we have to stay on guard.”

The county still needs to be prepared for worst-case scenarios, officials said.

Seventy-six Republican lawmakers want more specifics, and they want them by Tuesday.

“It is time for your administration to abandon its overbearing and authoritarian approach and show the country that the COVID-19 emergency is over,” they wrote in a biting letter to the president and Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra.

Their impatience is evident in opinion polls. In late February, 58% of Americans agreed that controlling the coronavirus should remain a priority, “even if it means having some restrictions on normal activities.” But 38% told an ABC News-Washington Post poll that “having no restrictions on normal activities” was more important.

The pandemic forced the federal and state governments to depart from their customary practices in myriad ways, and the public health emergency declaration makes that possible.

It allows the FDA to grant emergency use authorization to new medicines and devices, and either lets the federal government pick up the tab for their use or require insurers to cover them without a co-payment. It also gives the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention the authority to require face masks on planes, trains and other types of public transportation.

The federal recognition of a health emergency cleared a path for governors to make emergency declarations of their own. That gave them the authority to issue stay-at-home orders, implement mask and vaccine mandates, and protect residents facing eviction because they fell behind on their rent or mortgage, to name a few examples.

Washington’s action also provided legal and political cover for the governors and — sometimes — federal resources to carry out their orders.

The federal government’s $19.3-billion program to accelerate the development of COVID-19 vaccines relies on powers made possible by the public health emergency declaration. The use of military and other government resources to distribute the shots and other drugs does as well. And without the declaration, a president would court legal challenges by invoking the Defense Production Act to essentially coerce companies to make personal protective equipment and other pandemic necessities.

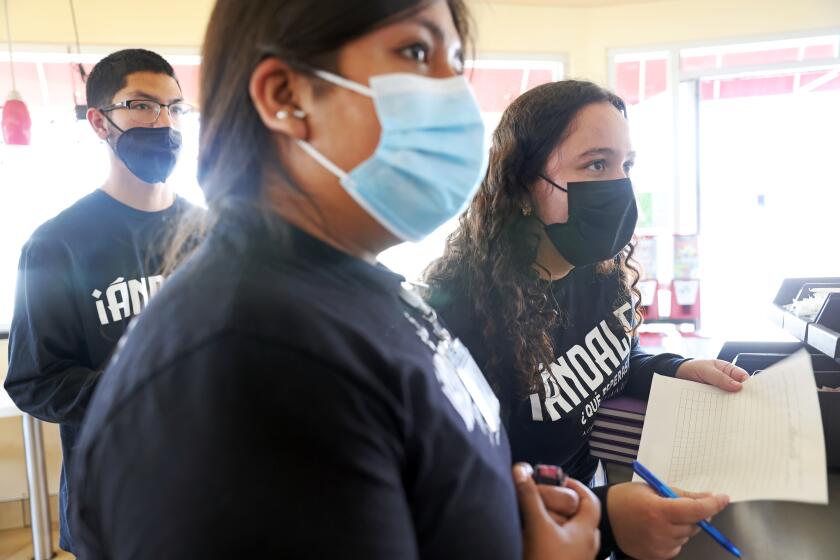

As the Omicron variant infects record numbers of people, many in Southern California say they are no longer willing to hide from a virus that has already killed 800,000 Americans.

Other extraordinary pandemic measures were less evident to the public. Because of the emergency declaration, Washington was able to give states lots of latitude in how they spent the federal funds they received for public health; that way, they could shift money and manpower from other programs as needed to fight the coronavirus.

Beyond that, the emergency declaration made it easier for healthcare providers to practice in states where they weren’t formally licensed. And it gave doctors, nurses and hospitals practicing under extraordinary pandemic circumstances some protections against being sued over the care they gave to COVID-19 patients.

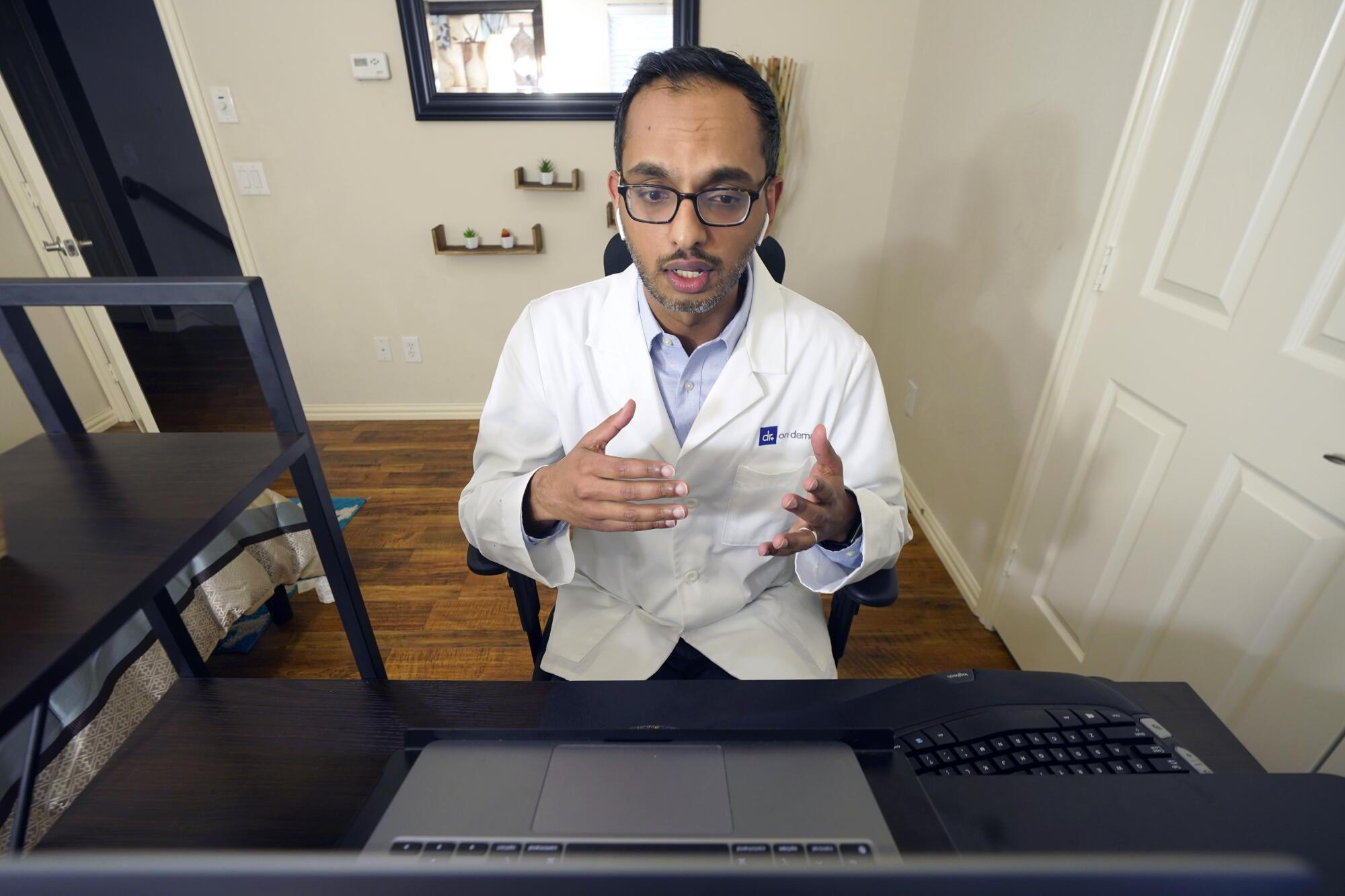

The use of telemedicine expanded for patients across the board, and insurers who refused to pay for it — or did so at a steep discount — were ordered to treat these virtual visits as if they had taken place in a doctor’s office.

The legal foundations for virtually all these extraordinary measures were in the federal declaration of a public health emergency, or in the states’ emergency declarations that flowed from that.

“It’s only a couple sentences long,” said Andy Baker-White, legal counsel for the Assn. of State and Territorial Health Officials. But he said its impact is sweeping — so long as it’s in force.

The declaration also limits the duration of these measures. Virtually all of the pandemic programs authorized and funded by Congress will wrap up when the health emergency expires, or after some specified period following that milestone.

“Once the emergency ends, the free lunch ends,” Gostin said.

Indeed, Americans have come to think that anything medical to do with COVID-19 — vaccines, tests, drugs — can be had on demand and at no cost, he said. But without the emergency declaration, a shot of vaccine or a course of Paxlovid could bring a sizable bill.

Remember all those problems we had with vaccine equity? Now they’re cropping up with new COVID-19 medications that are in short supply.

The impact would fall most heavily on those who can least afford to pick up the tab, experts said.

Tribal health services, which rely heavily on funds and powers granted by the federal government, would feel it first. And rural populations, where COVID-19 has hit hard, could see their struggling hospitals lose the emergency revenue they now rely on to stay open.

Under Biden’s new “test to treat” plan, Americans will need continued access to tests that don’t incur out-of-pocket costs, Gostin said. If they suddenly start coming with a bill, “you’d have a plummeting test rate in America, and it’ll drop the most in poor communities that are most at risk of COVID,” he added.

Low-income communities are also likely to bear the brunt of a key change in Medicaid, the health insurance program for disabled and low-income Americans.

In the Families First Coronavirus Relief Act signed into law in March 2020, Congress increased the federal government’s contributions to states’ Medicaid spending by 6.2% for the duration of the pandemic emergency. But the extra funding came with a condition: For the duration of the pandemic emergency, states accepting it were barred from disenrolling virtually anyone covered by the program.

This bit of fine print has had a major effect. In many states, a small increase in income or change in status will get a Medicaid beneficiary and his or her dependents kicked off the rolls, even if the change is just temporary. The Families First Act cut down this churn, ensuring that eligible Americans stay insured through the pandemic.

Elite commentators say COVID is over. That may be true for them but not for millions of others.

The law has been a particular boon to children, whose enrollment in Medicaid has grown by more than 11% during the pandemic. Today, more than half of all children in the U.S. are covered by these programs.

But that won’t last. Several states are already planning their return to standard practices when the health emergency ends. In addition to enforcing pre-pandemic income limits, many states will require all beneficiaries to re-enroll — a paperwork demand that will cause many low-income families to lose coverage.

Nearly 13 million Americans would find themselves without health insurance if the emergency declaration ends in mid-April, according to an analysis from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Urban Institute. And Georgetown’s Health Policy Institute estimates that in the first year after the end of the health emergency, at least 6.7 million children “are at very high risk of becoming uninsured.”