Column: If Miss America isn’t a beauty pageant, then what exactly is it?

In its early years, the Miss America pageant was just a beauty contest, a straightforward competition between eager young women with curvaceous figures and pretty faces. Baldly exploitative, gleefully sexist — it knew what it was about.

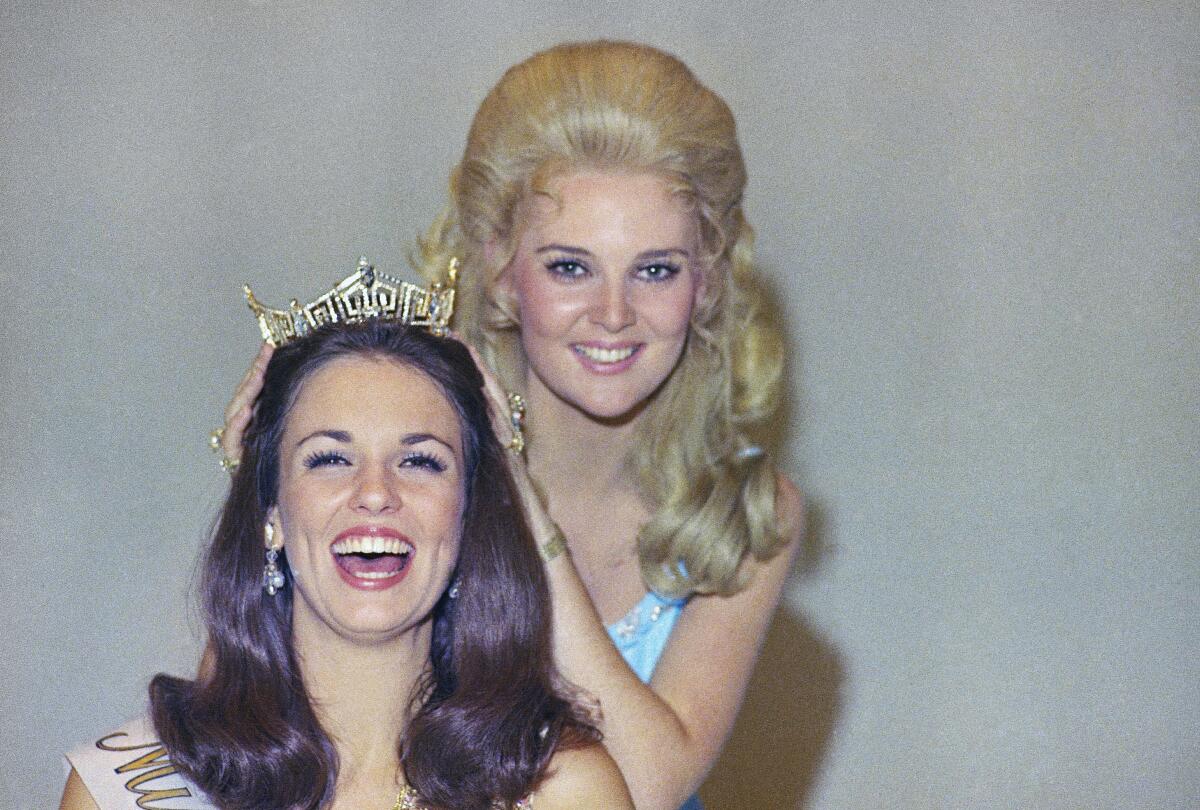

As it grew more popular, it sought respectability. Miss America was packaged as the virginal girl next door — white, of course — in a bathing suit or a gown, a sash and a crown. The pageant increasingly recognized intelligence, talent, poise and personality, and began offering academic scholarships to winners in the 1940s. But it was still, at heart, a meat market, pitting this “knockout in a swimsuit” against that “slender, auburn haired, blue-eyed lassie,” to use the breathless words of the Los Angeles Times’ coverage.

This year’s competition, which concludes Thursday, will be, to put it mildly, different.

We may think any of us can become the next Bezos or Musk. But in fact, social mobility is not really a thing in America anymore. Income inequality is.

This year is the 100th anniversary of the contest that began on the Atlantic City, N.J., boardwalk in 1921, and the organization is in a battle — a somewhat desperate battle, I can’t help thinking — to maintain its place in the culture.

And how is it doing that? Well, as the publicity materials note, the competition is evolving.

Since 2018, contestants, now officially referred to as “candidates,” are no longer judged on their looks or “outward physical appearance,” and the swimsuit contest is a thing of the past. The organization long ago dumped the term “beauty pageant.”

The event formerly known as the evening gown competition survived the 2018 makeover, but, oddly, participants were told they no longer had to wear evening gowns. Instead, they were offered ”the freedom to outwardly express their self-confidence in evening attire of their choosing while discussing how they will advance their social impact initiatives.”

The show-us-your-shoes parade remains. So does the outdated honorific “Miss.” Contestants for some reason still have to be unmarried and childless.

But, despite those perfunctory nods to the past, today’s Miss America competition is about “wellness.” And “body positivity.” And “empowerment.” And “social impact initiatives.”

I see the problem the organization faces, of course. It is indisputable in 2021 that Miss America’s 51 contestants should not be paraded on stage and judged on the color of their eyes or the shape of their bodies. Congratulations to the organizers for having recognized that obvious point after only 97 years.

But I can’t help wondering, what’s left?

What’s the point of a former beauty pageant that no longer recognizes beauty? Once you subtract the offensive objectification of women from the show, is there really any reason for it to exist?

Unsurprisingly, Miss America has been in decline for a long time, at risk of becoming little more than a campy nostalgia act. At its peak in the late 1960s, the pageant had over 70 million television viewers; in 2019, that was down to 3 million or 4 million, according to Margot Mifflin, author of “Looking for Miss America: A Pageant’s 100-Year Quest to Define Womanhood.“ As recently as the late 1980s, there were 80,000 contestants in competitions nationwide; now there are about 4,000.

But Miss America is a survivor. It refuses to go away.

From the start there were contestants who chafed against the rules, critics who railed against the whole idea, rebels who fought back — but in the face of challenges, the organization has repeatedly reinvented itself.

There was a time, for instance, when the pageant was restricted — under what was known as Rule Seven — to participants who were “of good health and of the white race.” It was only in 1983, six decades after the competition’s founding, that Vanessa Williams became the first Black Miss America. (She was dethroned a year later when naked photos of her were published in Penthouse. More than 30 years later, the organization apologized for the way the scandal was handled.)

In 1951, Yolande Betbeze created an uproar when she flatly refused to pose in a bathing suit for photos during her year as Miss America. “I’m a singer, not a pinup,” she said. (Even fully clothed, she received 163 marriage proposals during the year, according to Mifflin.)

I asked him to mask up and enlisted a flight attendant, but I settled for 11 hours next to a nitwit rule-breaking anti-masker.

In September 1968, feminists held a huge demonstration on the Atlantic City boardwalk, accusing the organization of racism, sexism and more. They compared the pageant to a livestock competition at a county fair and crowned a live sheep as part of their protest.

The organization evolved, slowly. The first (and, so far, only) Jewish Miss America was Bess Myerson in 1945. The first contestant to come out as gay was Erin O’Flaherty, in 2016. She didn’t win.

No Muslim or Latina woman has ever won.

In 2017, a scandal broke out. The Huffington Post uncovered emails between executives at the organization calling one former Miss America “huge … and gross” and another a “blimp,” and referring to all former Miss Americas by a deeply derogatory term.

The chief executive resigned. New management rolled out “Miss America 2.0.” Body positivity became a thing.

Few would deny the organization has made positive contributions. It promotes education, awarding millions of dollars in scholarships to winners. It focuses on careers, talents, social impact, health. Those are all good things.

Still, to me, the competition has always seemed like a relic, and today’s self-improvement buzzwords ring a bit hollow.

Whether there’s space in popular culture for a feminist-friendly, wellness-focused, non-beauty beauty pageant remains to be seen.

But Miss America’s symbolic role will no doubt endure, because what historian Rosalyn Baxandall said about the pageant more than 50 years ago still rings true on its 100th birthday: “Every day in a woman’s life is a walking Miss America contest.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.