Op-Ed: Homicide rates are up. To bring them down, empower homegrown peacekeepers

As COVID-19 tightened its deadly grip on our country this past year, Americans also suffered an increase in violent crime. One study documented a 30% rise in homicides, an unprecedented single-year jump. Los Angeles was not spared, logging more than 300 killings for the first time since 2009.

Some criminologists suspect the increase is a pandemic-related aberration, noting that crime rates have been trending steadily downward since their peaks in the early 1990s. But even if the spike subsides along with the coronavirus, the United States will remain a violent nation, suffering far more homicides per capita than any other wealthy country.

There are proven ways to tamp down the violence. We know community-based violence-intervention programs can help. In fact, pandemic-forced cutbacks in such on-the-ground peacekeeping may be a large part of the explanation for the surge in killings. Those of us who work in intervention lost precious ground in 2020, but we can move forward again.

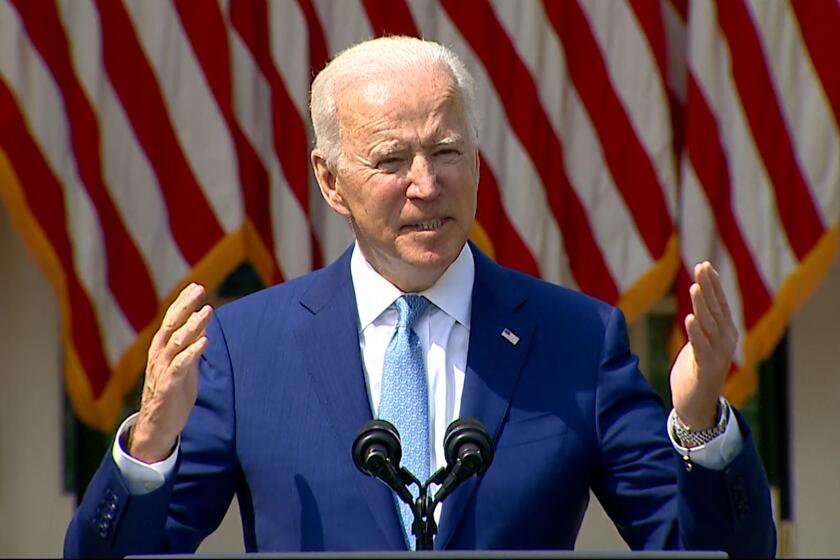

President Biden has offered to help. Tucked within the massive infrastructure proposal he unveiled last month, the American Jobs Plan, is $5 billion earmarked for “evidence-based community violence prevention programs” over the next eight years. As part of his gun plan announced Thursday, Biden is asking federal agencies to find money in existing programs to bolster intervention efforts immediately.

Biden’s proposals would require background checks for ‘ghost guns,’ encourage state red-flag laws and more. Yet they stop short of what advocates seek.

These are encouraging gestures. But will violence intervention survive months of horse trading as Congress wrestles with bills to enact the president’s enormous jobs plan? Lives depend on the answer. First, let’s consider how COVID-19’s challenges influenced community efforts to reduce violent crime.

In Los Angeles and other big cities, the pandemic created tremendous levels of stress and despair in communities of color, neighborhoods already at a disadvantage. Lockdowns and school closures increased tensions within households. Businesses shut down, unemployment skyrocketed.

Midway through the year, George Floyd’s death beneath the knee of a Minneapolis police officer exacerbated the edgy emotions — and reminded many people of color of their own traumatic mistreatment by some in law enforcement. Most responded through peaceful protest, but others turned to violence. Although 2020 homicide rates outpaced 2019 during every month of the year, the single biggest increase was in June, coinciding with mass demonstrations over Floyd’s killing.

Throughout the pandemic, violence-intervention programs, which depend on face-to-face interactions, were necessarily curtailed. The 16 agencies and groups that convene as the Los Angeles Violence Intervention Coalition — including the program I founded — estimate that our collective proactive efforts were cut in half.

In normal times, violence-intervention workers — we call them peacemakers — are a constant presence in at-risk communities, offering safe passage at schools, assisting gunshot victims at hospitals and negotiating between rival gangs. They focus on the young men most at risk of committing violence — and becoming victims of it.

The reality is that the majority of homicides in the U.S. involve young men who live in Black and Latino communities, lack economic opportunities and a reliable support system, and become ensnared in deadly cycles of retribution. A recent analysis by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention illustrates the heavy toll. It found that while Black men and boys ages 15 to 34 make up just 2% of the nation’s population, they represent 37% of gun homicides. That’s 20 times higher than white males of the same age.

Data from Los Angeles show the effect violence intervention can have on such statistics. In 2017, a joint UCLA-USC study looked at the effect of peacemakers in South L.A. It found that over a two-year period intervention workers reduced retaliatory gang violence by more than 43% overall. When a gang-related homicide was responded to by police alone, the chance of a retaliatory killing was 26%. But when police plus peacemakers responded from their separate lanes, the chance of a retaliatory homicide fell below 1%.

In 2018, Los Angeles experienced its second-lowest number of homicides in more than 50 years, a milestone that sparked inquiries about our violence intervention programs from other cities around the globe.

Now we must convince Congress.

The $5 billion allocated in the American Jobs Plan would be a historic investment in preventing everyday carnage in many urban communities. The desperate need was described in an open letter last month to Biden and Congress from #FundPeace, a coalition of activists working to end gun violence.

One road map for how to use part of the funding — strategic assistance to the 40 cities hit hardest by homicide — was outlined by a task force of the nonpartisan Council on Criminal Justice. By one estimate, a $900-million investment in violence-reduction grants to those cities over eight years could cut homicides by half, saving lives and billions of dollars in social and taxpayer costs.

The evidence tells us that would be a great start. As a new normal emerges from the pandemic year, we must invest in what we know can make the future safer.

Paul Carrillo, director of the Community Violence Initiative for the Giffords organization, is cofounder of Southern California Crossroads in Los Angeles and a member of the Council on Criminal Justice.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.