Editorial: A judge is forcing L.A. to do things his way on homelessness. Is he helping or hurting?

Depending on your point of view, U.S. District Judge David O. Carter is either a fearless disruptor of slow-footed government — or a bully interfering with professionals dedicated to housing and serving homeless people. In fact, he has been both.

Carter is overseeing an agreement between Los Angeles city and county governments in a case brought by the L.A. Alliance for Human Rights, a group of downtown business owners and residents that sued to force the city to shelter homeless people. Carter is requiring the city to find temporary shelter or permanent housing (with the county footing the bill) for several thousand homeless people — mostly those living under or near freeways, because the judge has decided that it’s unsafe to live near the toxic fumes from vehicles.

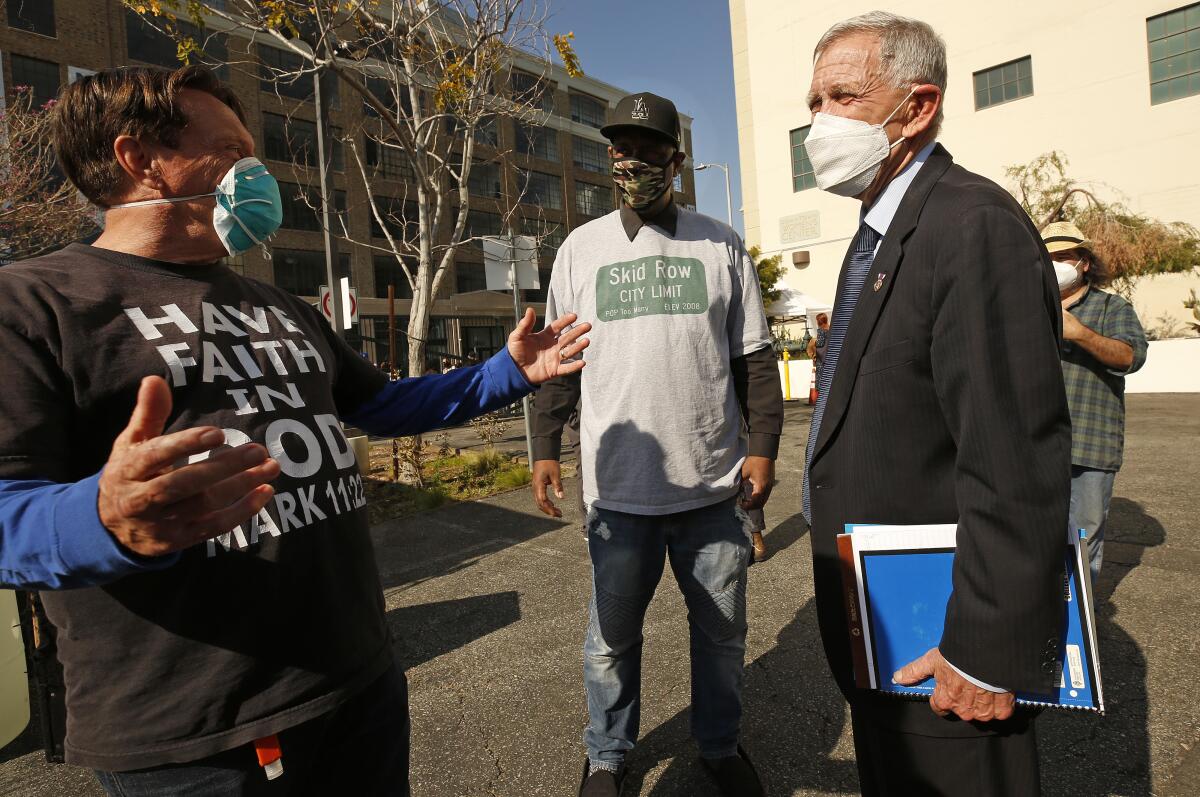

The mandate has forced the city and county to spring into action, moving scores of homeless people from highway underpasses and overpasses to shelter beds and providing them with services. And Carter has continued to hold officials accountable for the problems he has encountered on his frequent visits to L.A.’s skid row neighborhood.

Yet the judge can also be an impediment when he substitutes his judgment for those of professional service providers and outreach workers regarding the issue of who should be helped first. His declaration that homeless people near freeways should be given priority during the pandemic upended a smart plan by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority to prioritize the older or ailing homeless people most vulnerable to getting seriously ill from COVID-19.

The city and county still managed to shelter some of those vulnerable homeless people in FEMA-funded hotel and motel rooms secured through Project Roomkey. But fulfilling Carter’s mandate to shelter people near freeways took time and resources away from thinly stretched service providers.

On a rainy morning this month, Carter was walking on skid row when he encountered a number of drenched homeless women near the Downtown Women’s Center. He erupted in anger and insisted that the women’s center cover its parking lot with a tent and offer it as a campground for the women. He also made city officials find shelter for a variety of women that night. Then he called a court hearing several days later — in that same parking lot — and demanded to know what city officials were doing about getting people sheltered or housed on skid row.

In fact, the Downtown Women’s Center has provided services and housing to women on skid row for years, and it was in the process of converting the parking lot into a campground. Meanwhile, city officials had already put in bathrooms and mobile showers and opened a new shelter to help skid row residents transition into permanent housing.

Upset by what he saw on skid row, Carter suddenly appeared to be giving new marching orders to city officials. You can’t employ a caped crusader approach to homelessness policy in a city with more than 41,000 homeless people.

No one blames Carter for being outraged by the sea of desperate humanity in skid row every day, rain or shine. It is outrageous. And homelessness has only gotten worse in L.A., even as the city moves thousands of people off the streets each year.

Maybe Carter — with a little less bombast — could be a catalyst for a new, more urgent approach to homelessness. Carter wants the parties to the lawsuit to agree to a settlement that sets enforceable goals. One way to achieve that would be a consent decree that lays out those goals and a deadline for the city and county to achieve them.

This isn’t a case of a consent decree being foisted upon a disengaged or antagonistic government that has done nothing about homelessness. Instead, it’s a government that hasn’t done enough and has taken far too long to do it. Among other things, a consent decree could force the city to speed up the painfully slow process that developers of housing for homeless people go through to get their permits and entitlements.

Any consent decree would have to include not just shelter for homeless people, but also permanent housing. Otherwise you’re just warehousing them forever. Housing is the only thing that makes a lasting dent in homelessness. But permanent supportive housing is expensive, and if the city is going to build it, it needs more financial aid than it’s getting today. That will be a stumbling block to crafting a meaningful consent decree that all can agree on.

A consent decree is not itself a magic wand. But if Judge Carter has one, he should start using it right away.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.