Op-Ed: California’s bullet train isn’t just fast transit, it’s a way to bridge the divide between rich and poor

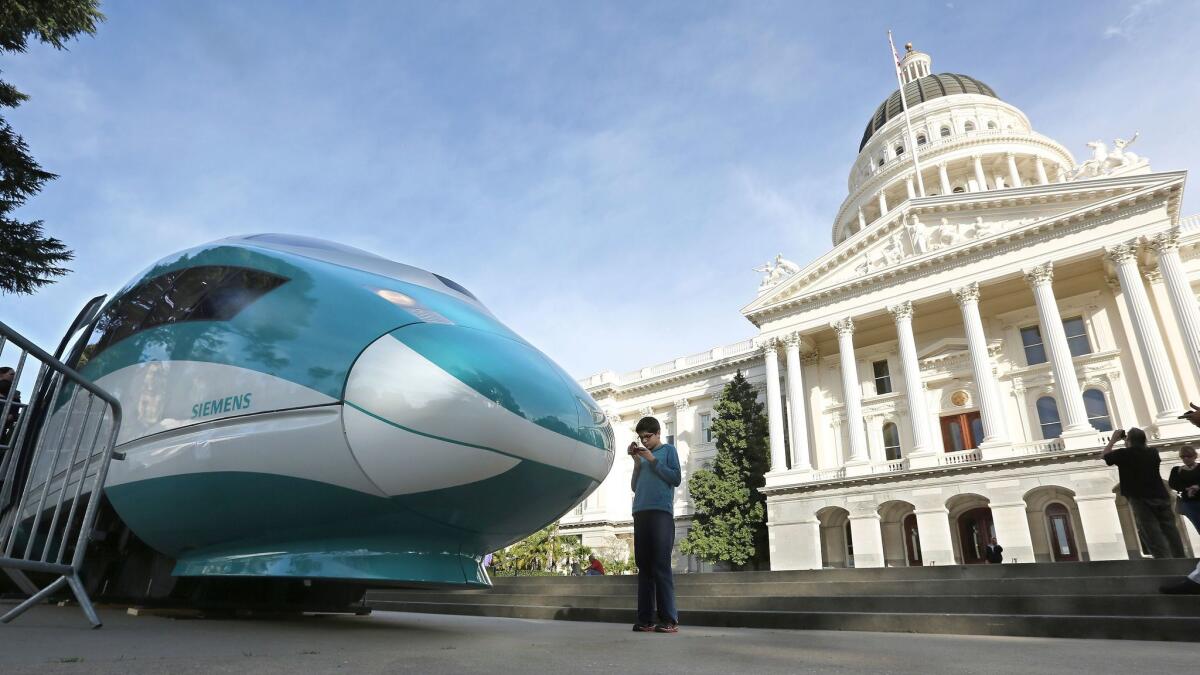

In the seesaw battle over California’s bullet train, it’s easy to overlook the reasons why the project should be built — and why there’s still a good chance that it will be.

On the seesaw’s upside, construction for the train’s first phase, which will connect Silicon Valley and the Central Valley, is underway. Project planners say that by 2025, passengers will be able to travel between San Jose and Fresno in an hour, a prospect they hope will build support for the rest of the project.

But the downside seems ominous. Next year, voters will decide on a ballot measure that would require a two-thirds vote of the Legislature to use the state’s cap-and-trade revenue to fund the train. Republicans devised the measure as a way of stopping the project.

On top of that, two convoluted recent court decisions — one in the California Supreme Court and the other in federal appeals court — increase the likelihood that the train will face a spate of environmental-impact lawsuits. Such suits probably won’t kill the train, but they could delay it.

Decades from now, Californians will be far less concerned with the bullet train’s cost than its success in meeting its lofty goals.

These ups and downs fuel bullet-train controversies, while the larger context is often ignored. For a project of this size — now pegged at $64 billion, making it one of the largest infrastructure projects in the state’s history — delays, cost overruns, near-death experiences and outraged opposition are more or less predictable.

As Dan Richard, board chair of the California High-Speed Rail Authority, told me: “The vote on the state water system in the ’60s passed the Legislature by one vote. Gov. Pat Brown’s master plan for the University of California passed by one vote. The Bay Area Rapid Transit System was passed by one vote of county supervisors. Yet it’s unimaginable that we’d have the state we have without those things.”

The train’s biggest vulnerability is its mounting cost. Overruns are a failing of virtually all high-speed rail projects. According to Bent Flyvbjerg, an expert on mega-projects at the University of Oxford, these systems are among the most likely of all transportation projects to experience overruns, and their forecasts of passenger use are typically over-optimistic by 30% to 50%. Most of the systems require perpetual subsidies, he said — but, he adds, that “is not necessarily an argument against them.”

Because money isn’t everything.

Here’s what’s at stake: If successful, the nation’s first high-speed rail system will integrate California’s affluent coast and its poor interior — among other ways, by cutting travel times from the San Joaquin Valley to Los Angeles and the Bay Area enough for some valley residents to commute to coastal jobs. It will form the backbone of the state’s attempt to reduce the role of conventional cars in favor of light rail, ride-sharing, bicycles and electric, even driverless cars. Central Valley locales that house the rail line’s stations — initially, Madera, Fresno and sites near Visalia and Bakersfield — will be transformed too as development radiates from the stations.

California’s population, now 39 million, is expected to grow to 50 million by 2055, putting more strain on already clogged highways and airports. Shifting some of those travelers to the bullet train would almost certainly reduce road and air traffic congestion, car accident casualties and fossil fuel emissions. A 2012 analysis by Caltrans and the High-Speed Rail Authority estimated, perhaps optimistically, that in the first 50 years of the train’s life, it will reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 58.7 million metric tons. That number sounds grander than it really is — it’s the equivalent of a little more than a third of the California transportation sector’s emissions in 2014 — but it still moves the state closer to its ambitious renewable energy goals.

The expense of a bullet train must also be measured against the costs its absence would incur, most notably in the form of other transportation infrastructure that would have to be added, such as highway lanes and airport gates and runways. The project’s 2012 business plan pegs that cost at $120 billion to $180 billion — a number that, even if inflated, makes the cost of high-speed rail look far more reasonable.

There’s no guarantee that the project will flourish. That depends on its management and an array of factors outside management’s control. Local governments along the route will have to support the system by making land-use decisions that treat new stations as potential economic hubs and provide sustainable transportation connections to them. If they surround the stations with parking structures instead, they’ll just promote more sprawl.

Driverless cars could become the bullet train’s rivals, or they could complement the system by smoothly delivering passengers to stations and promptly departing. The train could reduce the income divide between the rich and poor sides of the state, or it could extend L.A.- and S.F.-style gentrification into the Central Valley, deepening the rich-poor divide.

What is certain is that decades from now, Californians will be far less concerned with the project’s cost than its success in meeting its lofty goals. It’s not just that its ascendance would reinforce the state’s status as a pioneer of forward-thinking policy: The bullet train is the rare transportation project that could foster a more habitable, sustainable and equitable society.

Jacques Leslie is a contributing writer to Opinion.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.