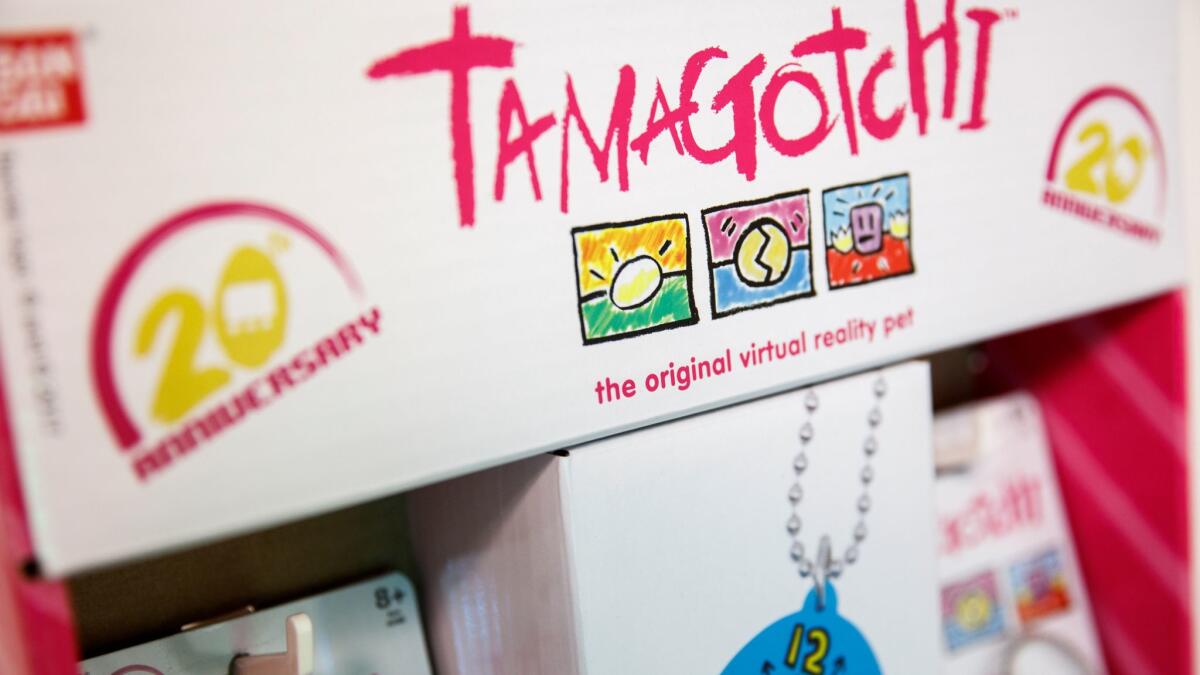

Did your Tamagotchi die of neglect in the late ‘90s? Now’s your chance to take another shot

Before fads such as the fidget spinner and Furby, when the world was just getting acquainted with the Backstreet Boys and clamoring to watch “Titanic” in movie theaters, there was the Tamagotchi.

The Japanese digital pet on a keychain was a sensation, racking up sales of 82 million units since its release in 1997. It was a precursor to mobile gaming, a pocket-sized electronic device that taught legions of children to feed a pixelated critter and pick up after its business.

It was also controversial, as fads tend to be, having been blamed for being too morbid (the pet died if you didn’t feed it) and its screen too addictive (you had to tend to it every 15 minutes). If they only knew.

On Tuesday, the company behind the gizmo announced plans to re-release the Tamagotchi in the United States to mark the toy’s 20th anniversary (the device had remained available in Japan). Buyers can begin pre-ordering the toy online before it is made available in stores nationwide Nov. 5.

Bandai America Inc., a subsidiary of the Tokyo-based Bandai Namco Holdings Inc., hopes children of the iPhone generation will embrace the retro gadget while also banking on ’90s nostalgia to drive sales.

Like clockwork, the decade that gave us grunge, Tommy Hilfiger jeans and the Game Boy is cool again. It’s perhaps why Nintendo has quickly sold out of its relaunched retro consoles and pop star Katy Perry dangled a white Tamagotchi from her Prada gown at last year’s Met Gala.

So confident in the gadget’s appeal was Bandai America, the El Segundo company best known for making Power Rangers toys, that it didn’t even conduct market research or focus groups before deciding to re-release the toy, an executive said.

“For many Generation X kids, the Tamagotchi device can be considered America’s first and favorite digital pet,” said Tara Badie, marketing director for Bandai America. “The enduring power of Tamagotchi is its clear expression that nurturing and love never goes out of style.”

The return of the Tamagotchi comes at a time when toymakers have looked to the past for inspiration. Nintendo miniaturized its classic NES and SNES consoles to great applause. My Little Pony has enjoyed a massive resurgence. And even Teddy Ruxpin, the wide-eyed bear from the 1980s that will either delight or terrify you depending on where you stand on animatronics, has made a comeback.

“Nostalgia works in the toy industry,” said Juli Lennett, a toy industry analyst for NDP Group. “Just look at Barbie and Hot Wheels. They appeal to kids the same way they did 30 years ago.”

To be fair, the aforementioned comebacks have been tweaked for today’s audience — and they haven’t always been as successful as their earlier iterations. Nintendo’s retro consoles come with a slew of preloaded games — but counts adults as a big market, not just youngsters. The newest Barbies smash tired gender roles, but they haven’t reversed declining revenues at Mattel.

There’s only one major change between the original Tamagotchi and its reboot: the new one is 20% smaller.

The suggested retail price of $14.99 remains about the same as when it was first introduced (the equivalent price of the original today would be closer to $23 if adjusted for inflation).

The egg-shaped toy comes in the same six original styles and colors. The gameplay features the same colorless blob that hatches, requires feeding and cleanup — chores that, if not undertaken, are penalized by death.

“The creature isn’t particularly cute, but it is demanding,” a highly skeptical Patricia Ward Biederman wrote in a column for the Los Angeles Times in 1997. “What it lacks in charm, it makes up for by beeping needfully every few minutes. It wants to be fed. It wants to be played with. It needs light. It needs medicine. It even produces digital dung that has to be cleaned up.”

But fans say therein lies the fun. Nurture is one of a handful of play patterns that transcends generations that the toy industry has traditionally directed at girls. When a nurturing toy appeals to both genders, as the Tamagotchi did, it usually signals a hit, and then imitators. For the Tamagotchi, rivals included the Giga Pet and the Nano Pet.

“The Tamagotchi took kids into a different world. They were in that screen taking care of that pet. It wasn’t the keychain or the color of the toy they cared about. It was the fact they could take it anywhere and it would still provide a form of escape,” said toy inventor and toy historian Tim Walsh, who could have just as well been describing the role the $46 billion mobile game industry plays today.

Walsh was specializing in board games at a toy company called Patch, now called Play Monster, when the Tamagotchi was released.

“I remember panic among the traditional game makers at the time,” Walsh said. “We thought electronic games would wipe us out. But we realized the two would always co-exist.”

Indeed, the threat of technology has often been overstated in the industry. Board games aren’t going away. And one need only look at the pandemonium surrounding fidget spinners to remain bullish on simple baubles. Other hot toys of the moment, such as L.O.L. Surprise dolls, also demonstrate that not everything requires a computer chip.

Still, Walsh wonders if children today, raised on apps and touch screens, will be wowed by a Tamagotchi reboot.

“It would kind of be like getting kids to watch movies from the 1970s, which are edited so much slower,” he said. “But I’ve been wrong before. The hardest thing in this business is trying to predict the fickleness of kids.”

Follow me @dhpierson on Twitter

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.