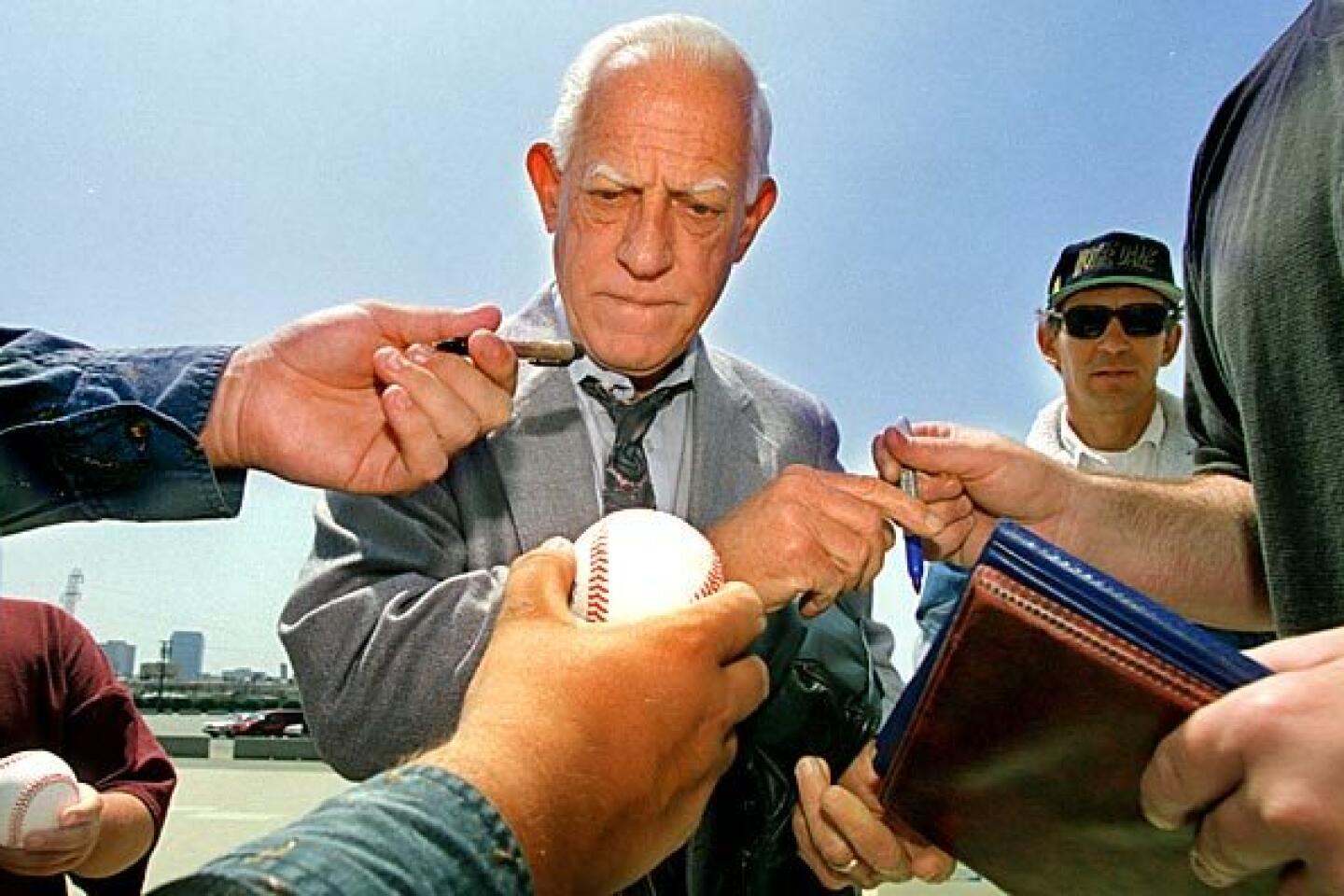

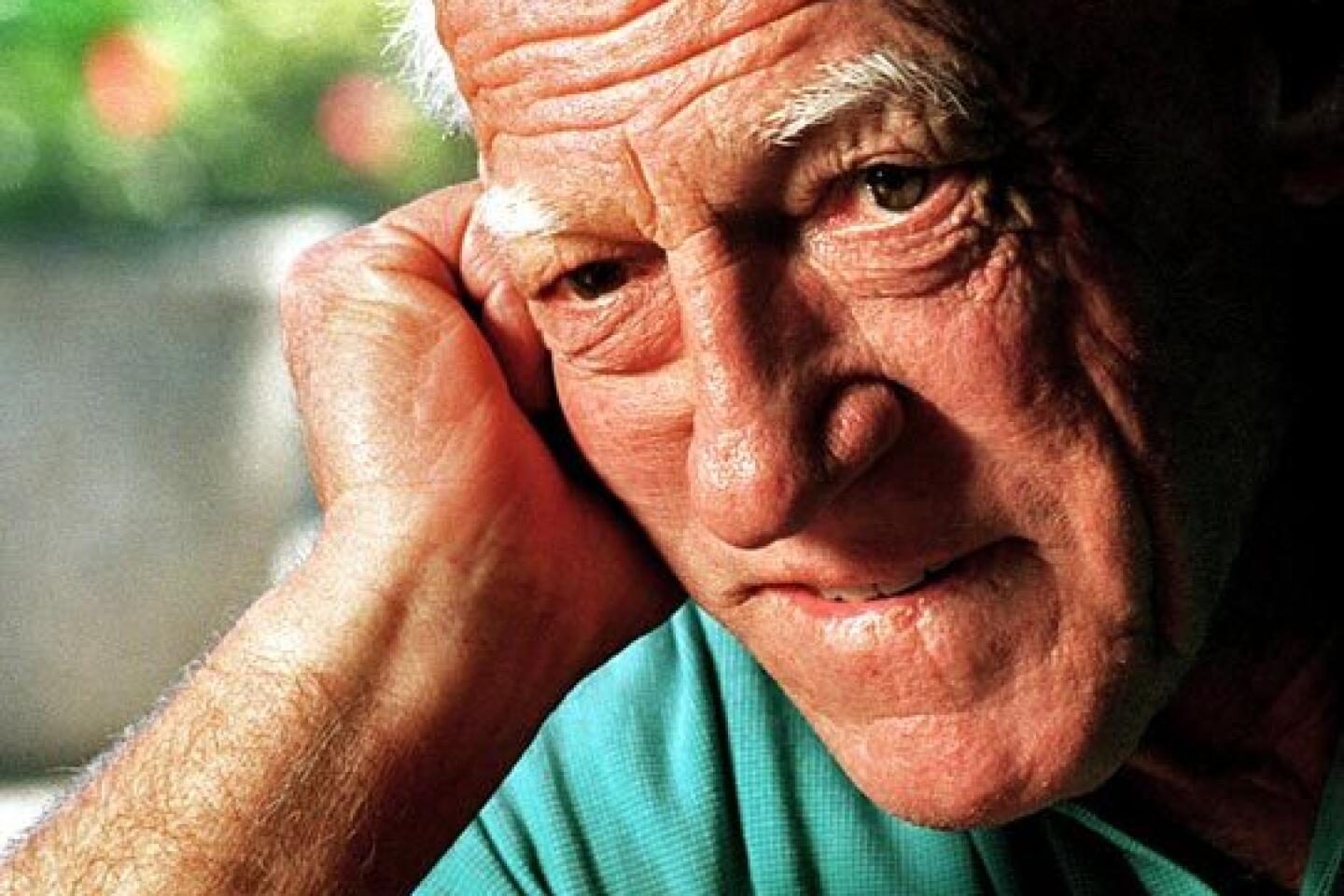

Sparky Anderson dies at 76; Hall of Fame manager of Cincinnati Reds, Detroit Tigers

- Share via

George “Sparky” Anderson, baseball’s first manager to lead teams from both the National and American leagues to World Series titles, died Thursday. He was 76.

Anderson died at his home in Thousand Oaks of complications from dementia, family spokesman Dan Ewald said in a statement. Anderson’s family announced Wednesday that he was under hospice care.

Anderson’s Cincinnati Reds won championships in 1975 and ’76 as one of the dominant teams of the era. Nearly a decade later, his Detroit Tigers won the 1984 World Series. He was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame in 2000.

“There’s a difference between a good manager and a great one,” Johnny Bench, Anderson’s Hall of Fame catcher with the Reds, told The Times in 2000. “The good one will tell you there’s more than one way to skin a cat. The great manager will convince the cat it’s necessary. Sparky had the cats carrying the knives to him.”

George Lee Anderson was born in Bridgewater, S.D., on Feb. 22, 1934, and his family moved to Los Angeles before he was 10. A standout player at Dorsey High School and a batboy for USC’s baseball team, Anderson began his professional career at 19, signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers’ organization.

His career as an infielder stalled in the Dodgers’ minor league system, and he reached the big leagues only after being traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. He hit .218 in 1959, his only season in the majors. By 1964, Anderson was managing in the minors.

All this made him an unlikely choice to take over the Reds in 1970. But Cincinnati General Manager Bob Howsam had hired Anderson to manage in the St. Louis Cardinals’ organization and now turned to him to mold his young and talented team.

“Anyone who says they knew about me before Howsam hired me would be lying,” Anderson told The Times’ Ross Newhan. “Well, I don’t know how you measure what you owe someone, but I do know that everything we have in our house has to belong to him. If he doesn’t hire me, chances are I never manage in the big leagues.”

In 1969 Anderson was a coach with the expansion San Diego Padres for Manager Preston Gomez, another former Dodger. Before agreeing to manage the Reds, Anderson had been set to join the Angels in 1970 as a coach for Lefty Phillips, who had signed him with the Dodgers.

“His work ethic was extremely important,” Howsam told the Rocky Mountain News in 2000. “He didn’t beat around the bush. He was right to the point. And the way he developed young players was very important. We needed that type of thing.”

But Cincinnati was underwhelmed by the hire. “Sparky Who?” was the headline in the Cincinnati Post.

“I think a lot of [the Reds] thought, ‘He’s a fly-by-night guy, and what’s this character all about?’ I wouldn’t blame them,” Anderson said.

The Reds quickly flourished under his leadership, winning 102 games in 1970 and reaching the World Series, where they lost to the Baltimore Orioles in five games. They became known as the Big Red Machine, led by future Hall of Famers Joe Morgan, Tony Perez and Bench — and another star, Pete Rose, baseball’s all-time hits leader whose chance for the Hall of Fame was doomed when he was banned from the sport for betting.

Anderson was direct even in the way he changed pitchers. He became known as Captain Hook for his quick, no-nonsense meetings at the mound.

“I didn’t want no conversation. They’re not happy. I’m not happy with what I’m seeing. There’s no sense for conversation,” he told the Rocky Mountain News.

The Reds reached the World Series in 1972 but lost to the Oakland A’s. They won a division title in 1973 but didn’t return to the World Series until 1975, when the Reds defeated the Boston Red Sox in seven games despite being on the losing end of one of baseball’s most dramatic finishes.

Carlton Fisk won Game 6 for the Red Sox with a 12th-inning home run that hit the Fenway Park foul pole, with Fisk waving his arms as if to keep the ball fair. But the Reds came back to win the deciding seventh game with a single by Morgan driving in the winning run.

The Reds swept the New York Yankees to win the 1976 World Series, but Anderson was fired in Cincinnati after two second-place finishes and a change in the front office when Dick Wagner became general manager after Howsam retired. He wasn’t out of baseball long. Anderson was hired by Detroit in June 1979 to guide another young team. But this time he was far from an unproven manager.

“With Sparky, it was never just about baseball.... He was another father figure,” Detroit shortstop Alan Trammell told Newhan in 2000. “We were a young club that needed direction when he took over, and he brought leadership and a presence to the clubhouse.”

The Tigers’ best season by far was 1984, when they jumped to a 35-5 start and never looked back, winning 104 games and dominating the San Diego Padres to win the World Series in five games.

“Sparky would go to great lengths to make sure I understood what it meant to be a big leaguer and how to approach the game on a daily basis,” Kirk Gibson, the Tigers’ star right fielder, told Baseball Digest. “His words were that if I didn’t do it, ‘I’ll send you home crying to momma.’ ”

The Tigers won another division title in 1987, and Anderson remained in Detroit until he retired after the 1995 season. He stayed away from the game for a time during a strike when baseball used replacement players. His absence reportedly angered Detroit management.

Like many retired players and managers, Anderson spent some time broadcasting, including doing Angel telecasts in the late 1990s.

“I think the greatest thing about Sparky is that he really does feel that he was blessed. He is as modest as anyone who will ever reach the Hall of Fame,” Vin Scully said in 2000. Scully met Anderson when he was a Dodger minor leaguer, and they worked together on World Series broadcasts for CBS radio.

Sparky was a fitting description of Anderson as a player and manager. With the Reds and Tigers, he would walk on the field with both hands in his back pockets, a habit he said that started after an argument with a minor league umpire turned physical.

Anderson called the nickname “the biggest break I ever had. … George? There are a lot of Georges.”

Survivors include his wife, Carol; sons Lee and Albert; daughter Shirley Englebrecht and nine grandchildren.

No services are planned.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.