Allen Iverson doesn’t smoke weed anymore — a fact I learned after enthusiastically asking Allen Iverson about how often he smoked weed.

It was Friday afternoon, on the first day of October. We were sitting in a two-story home between Beverly and Melrose, Fairfax and Crescent Heights. In a few hours, the official launch party of Iverson ’96 was taking place in Hollywood, celebrating the Hall of Famer’s new marijuana business venture with Viola, a 10-year-old company founded by 16-year NBA veteran Al Harrington.

Ball Family Farms’ founder thinks L.A.’s social equity program could take a page from the sports scholarship playbook.

There was a buzz in the room, but the 46-year-old Iverson seemed to carry a different energy. He sat six feet away, wearing shades inside, which felt appropriately fly for the coolest human of my childhood and a bit unnecessary given his age. He wasn’t upset, and he wasn’t rude, but for the first three minutes of our conversation, something was off.

As I launched into a question about the business specifics — as if on cue — Harrington sat in the seat next to Iverson. Instantly, the shades came off. A smile painted his face. And Allen Iverson, one of the greatest basketball players of all time, stared at Harrington in awe, hanging on to every word, as he spoke calmly and confidently about their working relationship.

“It’s been a journey, bro,” Harrington said. “A year and a half, from educating him to the point where he was comfortable. Like really understanding what Viola was about.”

Harrington is many things — charismatic, friendly, empathetic and extremely smart. But above all, he is passionate about his second career. He is a true cannabis evangelist — and he’s still thrilled that he found another calling, beyond basketball.

Allen Iverson, right, has found a mentor in Al Harrington as they launch the Iverson ’96 strain for Viola. “This is my guy,” Iverson says, “which makes this so dope for me.”

“I’m beyond blessed that I was able to find my way so fast after the league,” Harrington said. “I was so passionate about the game, and I got that same passion for cannabis.”

You’re fortunate to find one of those passions in life. So to find a second one is both lucky and deserved for a man who clearly wants to go on this ride with people he cares about.

“His blueprint meant everything to me,” Iverson said about his business partner and mentor. “I’m still a rookie at everything that comes with it. But this is my guy, which makes this so dope for me. I’m dealing with a guy that I love and I know he loves me.”

There’s a thing that people do — especially men of power and influence — when they’re in a room, presenting themselves to others: The less they know, the more they pretend they are experts. Additionally, when a man is exceptional at one thing, he often thinks he is automatically exceptional at all things.

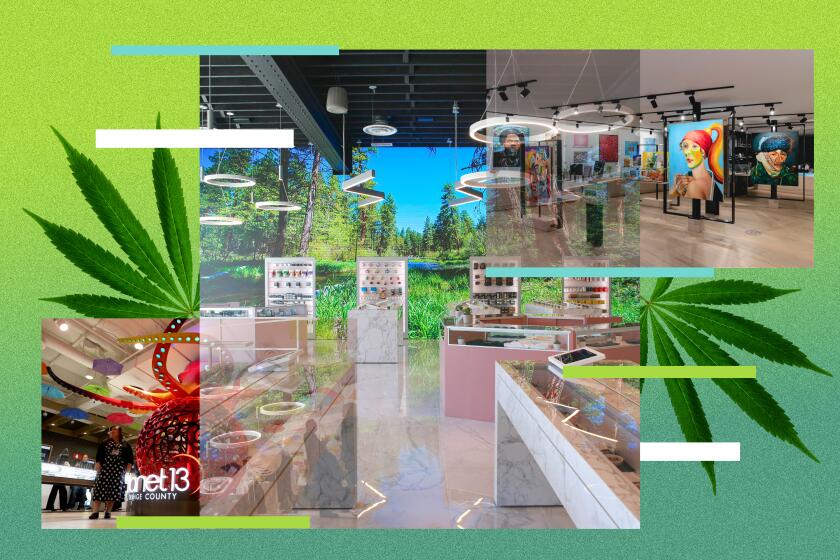

From art galleries and speakeasies to deli themes and circus vibes, dispensaries have gone next-level.

None of this is true of Allen Iverson. Sure, he has reemerged as a cultural titan in the last decade, a man who feels a lot and is searching for the true purpose of his post-basketball life. But in person, he carries himself much as he did during his 2016 Hall of Fame speech. The one where he hit the stage with tears already in his eyes and proceeded to use his time to thank the entire village that became part of his story.

First off, I wanna thank God for loving me.

I wanna thank Coach Thompson … for saving my life.

Tawanna Iverson … for loving me the way you do. And caring about what type of person I am.

Watching someone who has achieved unimaginable success believe he in no way got there on his own is truly beautiful to witness.

Iverson showed us a similar version of himself in 2020, not long after the tragic death of Kobe Bryant. The official memorial service hadn’t yet taken place. The league was grieving. Following a video tribute to Kobe in Chicago, Iverson ran into Dwyane Wade and hugged him tight. Not only was Iverson — dressed in a throwback yellow Kobe jersey — there to honor his friend, peer and on-court nemesis, he was grateful to be in the presence of others who loved him, hard.

Watching Iverson now — not as an ex-hooper but as a grown man — there’s something about him that screams community and connection. It’s clear why he and Harrington are collaborating. These tenets — community, connection — are the same ones that Harrington talks about when he explains how he landed in the world of cannabis. And why he believes in it.

“There’s something about cannabis that just brings connectivity. It’s fellowship,” Harrington said. “It allows people to let their guards down, have a conversation that you normally would not have, and next thing you know, it’s like, ‘Oh, we got mad s— in common.’ And I think that, for me, that’s the dopest thing about it all.”

::

Every few weeks this past spring and summer, a friend would come sit in my front yard to keep me company. I’d been sick, and that reality mixed with the pandemic made for a hyper-homebodied experience. During the hangs — typically one-on-one affairs — we’d smoke and have that two-years-overdue we just lived (and are still living) through some hard times catch-up. Each time my friend would leave, I’d go back upstairs, completely cleansed and recharged, feeling sad that it was over but fortunate for what we had.

Iverson wants these moments for other people, even though he no longer partakes. His life is full of memories when he was denied such simple pleasures, moments of reprieve.

In the run-up to 4/20, a look at some of the ways Southern California is shaping the cannabis conversation.

Take his arrest for possession of marijuana 24 years ago. I remember it like it was yesterday. I was 10, a kid in Atlanta. I remember how Iverson was vilified even as I knew what he represented: a culture that we knew to be good, one that many went to great lengths to stop.

Jumping into the weed business wasn’t the easiest decision.

“Just the thought of my name and cannabis,” Iverson said, aware that there will still be some people who label him negatively. “I’m thinking about the stereotype and stigma, what’s going to come with it. Because a motherf— loves to tell a negative Allen Iverson story. If I saved somebody from a burning building, they want to hear something about me missing practice.”

Al Harrington founded cannabis brand Viola 10 years ago. During his NBA career, he looked down on weed, but now it’s a passion. Cannabis, he says, “brings connectivity. It’s fellowship.”

Harrington is the perfect teacher, not just for Iverson, but for a generation of Black people who are understanding the benefits of weed in a very different way.

Harrington calls himself “the weed guru in my circle of people.” “People reach out to me all the time — my grandmother’s dealing with this, my brother’s dealing with that — and what’s amazing is that I’ll really be able to answer. I’m not a doctor, but I’ve seen more positive results than negative.”

Cannabis is a part of Harrington’s routine, but it wasn’t always. His evolution is part of what makes his journey so special. He used to look down on marijuana and the people who consumed it.

“My whole career I had teammates that smoked, and I always looked at them like they didn’t take this s— seriously, like they’d be a better player if they didn’t smoke,” Harrington said. “It’s funny, because now they’ll be like, ‘All that s— you used to talk, and now you’re the n— with the weed.’”

“I know what type of businessman he is. I know what type of vision he has,” Allen Iverson, right, says of Al Harrington. “And it was a compliment to me for him to feel like I was the right guy to make his vision come to fruition.”

Harrington has had 14 surgeries, a knee replacement, bad hips and other real aches and pains. When he started smoking, he noticed immediate results. “I got a way better quality of life because of cannabis,” he said. “The plant is amazing.”

What powers Harrington’s business is changing perception, moving with purpose and empowering people of color, especially Black people. He knows who has been the most negatively impacted by the laws surrounding marijuana and who has been the first group excluded from reaping the benefits of the newly legalized industry in various parts of the country.

“I know what type of businessman he is. I know what type of vision he has,” Iverson said of Harrington. “And it was a compliment to me for him to feel like I was the right guy to make his vision come to fruition.”

Pointing to his heart, he added: “It has to mean something right here for me to do it. It has to be something that’s real to me, to put a real stamp on it.”

::

Harrington does have a vision, both for Iverson and the company that he named after his grandmother Viola, whom he convinced to use marijuana to help with her glaucoma. He’s been through a lot over the last 10 years.

“I’ve been raided in Michigan, literally had my bank account frozen. And this is someone who played in the NBA 16 years, squeaky clean, never been in trouble a day in his life — that’s the s— I had to go through,” Harrington said. “When I think about all the s— and money I had to spend to get out of that, I think about regular Black people who never would be able to get out, would get locked up, would lose everything.”

Harrington is keen on intention. He wants his company to serve people in a meaningful way. On the packaging of Iverson ’96, it says, “premium flower with purpose.” He’s walking the talk, in a very real way, for the culture that he’s a part of.

“We’re purpose-driven. It’s really about using this platform to uplift, educate and empower,” Harrington said. “We make the product and we’re unapologetic. We make it for our people. I could have made a strain for him that was a sativa, but Black people like gas. Purple. Exotic-looking s—. We want that s— to look a certain way, taste a certain way, if his name is going to be on it, do you understand what I’m saying?”

I did. I really did. So did Iverson. We were both entranced by Harrington’s ability to make you feel like a part of something. More than anything, I was so happy that Iverson had found his person. And so was he.

“It’s about learning something new,” Iverson said. “Doing something that will obviously help people. Learning from a mentor, taking it all in and not being apologetic for the things that I don’t know.”

Iverson turned to Harrington and, briefly, they looked at each other. It was such a short but special moment, two men who are embarking on something truly special, something that could be a real part of their legacy to their families, communities and Black people.

“I don’t give a damn if I get to where I’m the biggest on planet Earth,” Iverson said, looking at Harrington. “It ain’t going to be without you.”

Rembert Browne is a writer from Atlanta. He lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.