This athlete’s weed side hustle turned into a movement to change L.A.’s cannabis scene

- Share via

Chris Ball walks through the cavernous supermarket-size warehouse space with the purpose of an athlete ready to hit the field. He’s wearing a gray tracksuit with black-and-white checkerboard accents, a pair of black-and-white checkerboard Old Skool Vans and a black ball cap with the brim facing backward.

Both the hat and the hooded sweatshirt are emblazoned with the name of his cannabis brand, Ball Family Farms, and its logo, a pair of crossed black-and-white checkered flags.

For the record:

3:16 p.m. Sept. 14, 2021An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the Drug Enforcement Agency. The federal agency is the Drug Enforcement Administration.

The athletic way the 43-year-old moves through the room is no accident; football skills earned the Rialto native a scholarship to the UC Berkeley training camp with the San Francisco 49ers (“I got released,” he said with a half-shrug), one season with NFL Europe’s Berlin Thunder and two with the Canadian Football League. But that was back in the early aughts — ancient history, really — and Ball only brings it up to explain how he came to fall in love with the plant side of the cannabis business.

“I went to play with the [British Columbia] Lions in Vancouver in 2004, and that’s where I saw weed being grown for the first time,” he said. “Before that, I had just bought it. A guy on my team had a little grow started, and I just kind of fell in love with it; watching the buds grow, watch the harvesting and the trimming — the whole process.“

Taking cannabis from seed to sesh connected me to the plant in ways I hadn’t expected.

Ball wasn’t new to the weed trade when he had his eureka moment. He had started selling pot when he was a teenager. “My first attempt was at 16, and that didn’t work. Then I tried again when I was 18 and that didn’t work either,” he said. “I guess I was trying for the wrong reasons. But when [my teammate] broke down the numbers and told me how much it cost him compared to what he was selling it for and what I could sell it for, it was a no-brainer.”

He explained that during the offseason, some of the football players (including him) would supplement their incomes by bringing weed into the U.S. from Canada. “I became very popular doing that because I was able to undercut the market here because I was getting it so cheap,” he said. “That’s when my status started to rise.”

Eventually, Ball said, a friend introduced him to someone who’d been on the Drug Enforcement Administration’s radar. “I touched a guy who was working for a very prominent drug cartel, and we started doing some weed business together,” he said.

In 2010, Ball and his younger brother Charles (now the chief financial officer of Ball Family Farms) took an ill-fated road trip to Arizona to sell cannabis. As the transaction unfolded, Ball said, he got a call that law enforcement was tailing the car with the weed in it. “We all broke our phones and scattered and didn’t talk to each other for a while,” Ball said. “And a month later, I’m in Miami at a friend’s party and I get a call on my phone that’s all zeros. I answered it, and the guy said, ‘Hello, Mr. Ball, this is the Drug Enforcement Administration.’ At that point my heart jumped down to my feet, and I’m changing my drawers.”

Ball said the DEA agent wanted to meet and talk, assuring him that he was not the target of the investigation. “We set up a meeting at my attorney’s office right off Slauson and La Cienega,” Ball said. “But when I get there, they’ve staked out the lobby, and I never made it up [the elevator] to meet my attorney before they arrested me.”

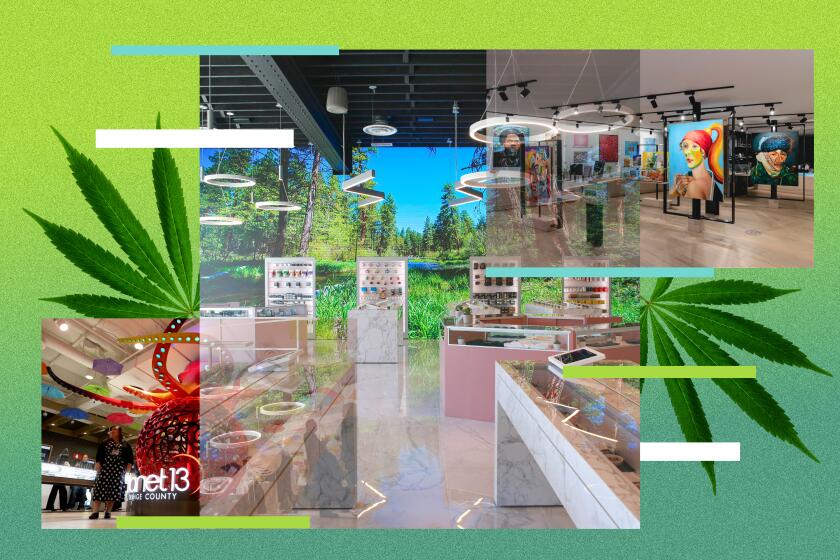

From art galleries and speakeasies to deli themes and circus vibes, dispensaries have gone next-level.

According to court documents, Ball was originally charged with conspiracy to distribute 1,000 kilograms of marijuana (an offense which carried a mandatory minimum sentence of 10 years). He said he spent about a month in jail, eventually taking a plea deal that he says left him facing 30 months in prison.

“After I signed [my plea agreement], my attorney worked out a deal with the judge and the DEA that said I didn’t have to report for sentencing until the case was over,” Ball said, adding that since the case involved multiple people, the result was that he didn’t face the judge again until 2014 — four years later.

“I worked at Abercrombie & Fitch for two years and at Nike [at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas] for another two. I kept a job, paid my taxes and pissed in a cup twice a week,” he said about his post-arrest career trajectory. “I had no issues, no arrests, no problems with the law, nothing [for four years].” When I went back to court to report for sentencing, the judge looked at me and gave me time served.”

There’s no way they’re going to give a guy with a felony for selling weed a license. I disqualified myself back in 2010.”

— Chris Ball

“But honestly, cannabis was just calling me back,” he said. “After all the things I’d learned up north in Canada about growing, I wanted to try my hand at cultivation. I knew there was a way for me to do it. So I started a 14-light grow in a little space in Van Nuys, and for the first year, I burnt up a bunch of plants while I learned how to grow by watching hundreds of hours of YouTube videos, reading [horticulturist and cannabis cultivation expert] Jorge Cervantes religiously every night and talking to friends who were growers.

In 2017, his landlord told him about the city of Los Angeles’ soon-to-launch social equity program. “I was like, ‘No f— way!” Ball said. “There’s no way they’re going to give a guy with a felony for selling weed a [cannabis] license. I [thought I] disqualified myself back in 2010.”

As Ball would soon find out, it actually made him more qualified. That’s because the city of Los Angeles’ social equity program, designed to help budding cannabis entrepreneurs who have been unduly affected by the war on drugs, uses prior marijuana-related arrests as one of three factors in granting a social equity license (having a low income and living in an area of the city disproportionally impacted by cannabis convictions are the other two).

Cannabis entrepreneurs complain that the sluggish rollout of L.A.’s social equity program is hurting some of the people it was supposed to help.

With the help of Ebony Andersen, a former urban planner who now serves as Ball Family Farms’ chief operating officer, Ball navigated a 10-month application process that, on June 2, 2019, made Ball Family Farms a legally licensed commercial cannabis distributor. A cultivation license followed four months later and, by October of last year, he had secured a manufacturing license (which allows the company to make things like pre-rolled joints and concentrates) too, making Ball one of just a handful of L.A.’s social equity applicants to have in-house operations capable of taking cannabis from seedling to dispensary.

It’s a business model that’s allowed Ball Family Farms to grow from four employees and a single strain of cannabis flower to 24 employees (20 of whom are people of color) and more than a half-dozen hybrid-heavy strains, and to plot an ambitious expansion that includes a delivery service, increased merchandise offerings, and a 75-acre grow facility 1,400 miles and two time zones away.

Eric Goepel, founder and chief executive of Veterans Cannabis Coalition, worked with Ball Family Farms to create the latter’s Hugs & Nugs compassionate care program, which provides free medicinal cannabis products to veterans.

He said Ball occupies a unique place on the industry landscape. “Chris is one of the only Black executives/owners in this space, even in California, where there’s a lot more diverse talent to draw from,” Goepel said. “You see very little Black representation anywhere in the C-suite in these businesses.” That, Goepel said, made Ball’s desire to launch the program, which rolled out around Memorial Day, all the more important.

“To have one of the only Black-owned and -led cannabis businesses in the country step up, especially in an industry where Black representation and [a] compassion for patients are largely absent, is an important step,” he said. “Not only in expanding the reach of cannabis donation [programs] but to remind the industry of why it exists at all.”

On a recent tour of Ball Family Farms’ cultivation operation (located in an industrial stretch of the city’s Harbor region, the building is camouflaged in plain sight but the address is kept under wraps for security reasons), Ball points around a mostly empty 20,000-square-foot ground-floor space like he’s calling a play.

“We’ll put 150 grow lights here,” Ball said with a wave of his hand. “We’ll have our manufacturing space down here. We’ll have a distribution center and a conference center too.” Although he’s been in the building for about three years, he’s only recently expanded into the downstairs space.

Until now, all the magic has happened in the 20,000 square feet on the second floor. He heads there next, striding up the stairs with all the confidence of a pro baller at the peak of his career on a pre-game tunnel walk. But instead of exiting onto a field of AstroTurf to the sound of a cheering crowd, Ball opens a door and is greeted with a sea of green cannabis plants and the low hum of high-powered lights.

This is one of BFF’s eight flower rooms, where cannabis plants (started in two nearby vegetative grow rooms) finish maturing. After harvesting, the plants will move again — to a not-as-brightly-lit but much warmer drying room where they’ll hang upside down until they’re ready to be sent off for packaging and distribution. (Currently done elsewhere, these last two parts of the process will eventually move in-house.) Right now the yield is about 3,000 pounds annually.

After the tour, Ball sat down to talk with The Times about his journey from football player to felon to farmer. Excerpts from that conversation, edited for clarity, appear below.

What role does family play in Ball Family Farms?

My younger brother [Charles] is the chief financial officer and my cousin Mikey [Ball] is the facilities manager, so that’s three Balls in the business right now. ... My goal is to pass [Ball Family Farms] down through our family. When I first got into this, I was like, “Yeah, if someone came along and wanted to give me a hundredmillion bucks, I’ll sell it right away.” But that’s changed. My goal is to [offer the same opportunities] the Nordstrom kids have or the In-N-Out family. If you want to go into cannabis — and I’d like the Ball family name to be synonymous with the cannabis space forever — the company will find a position for you. If not, whatever you choose to do, there’s resources for you to do those things. That’s the kind of generational wealth I’m talking about.”

Is collaborating with other Black-owned brands more important in the cannabis space?

We’re trying to work together because there’s strength in numbers. We’ve known for a long time that the [cannabis] industry was predominantly white so we want to make sure we support one another’s businesses. So we’re going to be major supporters of Josephine & Billie’s [a soon-to-open L.A. dispensary created by and for women of color, of which Andersen is a co-founder], and I did a partnership with Al [Harrington, former NBA player and fellow cannabis entrepreneur,] over at Viola. I want to keep doing things like that. I’m going to be partnering with Jay-Z’s brand [Monogram] as soon as I find a strain for them, and the same thing with [dispensary] Sixty Four & Hope and Aja Allen. … We’re all just trying to make sure we support one another and band behind each other so we can succeed in this industry.

Is there anything you learned playing football that’s helped you in the cannabis business?

Discipline and hard work — there’s no shortcut. The discipline of having to get up and go to practice every single day and run those plays every single day until they’re second nature. There’s no vacations in sports. ... The discipline it takes to play sports at an elite level is the same discipline it takes to work in the cannabis space and be good at it. ... Those plants don’t know holidays. They don’t know Christmas and Thanksgiving.

What’s one thing L.A.’s social equity program could do to make things easier on applicants?

I don’t think that the program is set up for success. I think they set the program up just to say that they did it. Like, “We gave you an opportunity. It’s not our fault you couldn’t figure it out.” The verbiage, the language, how it’s all structured is a complete setup for failure. Ebony Andersen turned out to be a lifesaver for us because she’s an urban planner by trade, so she understands the city. She used to work for the city, so she could actually help us navigate through the application process.

There’s no assistance in the program. I make the [sports scholarship] analogy all the time. If I got a football scholarship but had no place to live, no priority registration and no financial support, I’d flunk out of school. You’ve admitted me to the school, great. But where am I going to live? I don’t have any money. I’m broke. How am I going to eat? How do I register? ... My startup funding came from my illicit market days — what I call “shoebox money” because I used to keep it in a Nike shoebox.

Why is it important for you to control every step of the process from seed to sale?

The idea behind vertical integration is to own every aspect of the supply chain so we don’t have to outsource anything to anyone. We do our own cultivation. We do our own distribution. We have a license to do our own manufacturing. Eventually we’ll have our own retail location. If we wholesale for $25 for an eighth, a dispensary can turn around and sell it for $50, $60 or even $75 sometimes. What if we could get that $50, $60 or $75 ourselves instead of having to wholesale it to a bricks-and-mortar dispensary? And dispensaries are just a destination — the legal [version] of trap houses now. ... We’re thinking about a delivery service first. If we had it our way, we’d have a delivery and an app up and running in a year — depending on what’s going on with the city.”

How did your signature strain end up with the name ‘Daniel LaRusso’?

“The Karate Kid” was my favorite movie as a little kid. I was a huge karate fan, and our dad was a third-degree black belt. So when that movie came out, it got ahold of me like it got ahold of the rest of the world. I kind of like to go against the grain. So when we finally found the strain we wanted, instead of naming it after a gelato or an ice cream or some sort of candy or s— like everyone else does, I wanted to name it something that was meaningful to me. I thought about [Ralph Macchio’s character] Daniel LaRusso and how he was this underdog; he moved from Newark out to the Valley, and my first grow was in the Valley right next to Reseda. How he’s going up against this big conglomerate Cobra Kai and how I’m a Black grower going up against all these cannabros. So I decided to name the strain ‘Daniel-san.’ A friend of mine suggested using [the character’s full name] Daniel LaRusso and I was like, “Do you think so? Everyone knows Daniel-san. It’s so easy.” He said, “You don’t want everyone else to know. You want for the people who know to know and the people who don’t to go look it up.”

Why are you expanding your business to Oklahoma of all places?

We’ve got a license for Oklahoma, so we’re building a grow there from scratch. We bought 75 acres, and we’re pouring the concrete as we speak. It’s currently medical, but [I think] they’re going to going rec. The reason why we bought 75 acres in Oklahoma is that it’s in the middle of America, and we’re prepping for federal legalization. We can produce the same pound over there for a third of the cost [of growing in Los Angeles]. Once it’s legal federally I’m right in the center of America and can distribute it — ship it everywhere — from there.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.