Ian James is a reporter who focuses on water and climate change in California and the West. Before joining the Los Angeles Times in 2021, he was an environment reporter at the Arizona Republic and the Desert Sun. He previously worked for the Associated Press as a correspondent in the Caribbean and as bureau chief in Venezuela. Follow him on Bluesky @ianjames.bsky.social and on X @ByIanJames.

1

A Saudi dairy company that grows hay in Southern California and Arizona for export to the Middle East is set to lose several leases that allow it to pump unlimited water from government-owned farmlands.

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs announced this week that the state has terminated one of the leases held by the company, Fondomonte, and will not renew three other leases when they expire in February.

Aggressive and impactful reporting on climate change, the environment, health and science.

The action, although partly focused on details of the company’s rental agreements, reflects concerns among some political leaders about the use of water to export alfalfa and other water-intensive crops at a time when chronic shortages are prompting calls to rein in water use along the Colorado River and throughout the Southwest.

Fondomonte, a subsidiary of the Saudi dairy company Almarai, also owns thousands of acres of farmland in Arizona and California, producing alfalfa that is shipped overseas to feed cows.

The leases of state-owned land in Arizona have generated heated debate, because they have allowed the company to pay a below-market lease rate and not disclose its water use — despite concerns about the depletion of groundwater in one of the driest parts of the country. State officials said a review found problems that led them to act.

Hobbs, a Democrat, said she directed the State Land Department to conduct inspections of the largest leases of state trust lands, and found that Fondomonte had a “significant ongoing default of its lease” dating to 2016.

“It’s unacceptable that Fondomonte has continued to pump unchecked amounts of groundwater out of our state while in clear default on their lease,” Hobbs said in a written statement. She said her administration is acting “to hold defaulting high volume water users accountable and bring an end to these leases.”

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

Fondomonte said it will appeal the state’s termination of its lease and has contacted the governor’s office about “factual errors” in the decision.

The decision affects leases for 3,520 acres in a remote area of western Arizona desert called Butler Valley. The company also rents 3,088 acres of state farmland and other cattle-grazing lands under leases that aren’t affected by the decision, and owns 3,762 acres in western Arizona where it relies on pumping groundwater.

In California, the company owns 3,375 acres of farmland near Blythe, where it pays the Palo Verde Irrigation District a flat rate for Colorado River water to irrigate its alfalfa fields.

Arizona has been charging the company $25 per acre. And Fondomonte, like other companies that lease state land in Arizona, can pump unlimited amounts of water from wells at no cost.

Critics of the leases praised the governor’s action.

“I’m glad that it came to an end,” said Holly Irwin, a La Paz County supervisor. “We have a foreign company that is leasing land from the State Land Department in Arizona, mining our natural resource.”

She pointed out that Fondomonte began buying and leasing land in Arizona after Saudi Arabia phased out the growing of cattle feed crops because the country’s aquifers had been depleted.

“We can’t afford to have our aquifers just depleted,” Irwin said.

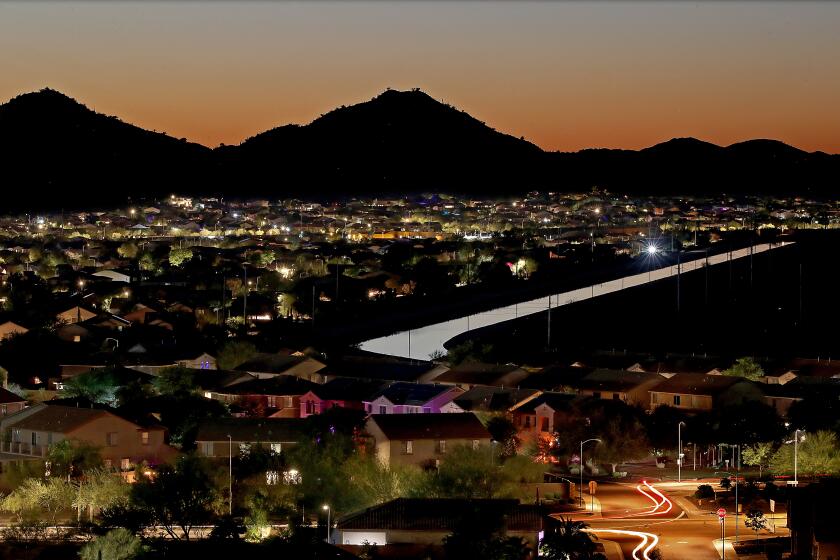

A water truck pulls onto a road next to a Central Arizona Project canal near the Fondomonte farm in Butler Valley, Ariz., in June.

(Caitlin O’Hara / For the Washington Post / Getty Images)

The leases began generating criticism after an investigation by the Arizona Republic in 2022 revealed the discounted, below-market rates the state was charging, and the lack of reporting about the amount of water being pumped in Butler Valley, an area where groundwater has been earmarked as a potential future water source for Arizona’s growing cities.

Irwin and other critics have said they are concerned the state is allowing overuse of groundwater on public lands, and that the state isn’t receiving nearly enough in exchange for the water that is being pumped to irrigate crops.

Barrett Marson, a Fondomonte spokesperson, said the state is mistaken and the company has been adhering to the conditions of its lease.

“We have done everything required of us under these conditions,” Marson said. “Fondomonte will continue to work with the state to demonstrate its compliance with the current lease requirements.”

Arizona will limit development in the Phoenix area after a study found the available groundwater isn’t sufficient to meet long-term water demands.

Marson said that not renewing the other three leases “would set a dangerous precedent for all farmers on state land leases, including being extremely costly to the state and Arizona taxpayers.”

“Fondomonte will explore all avenues to ensure there is no discrimination or unfair treatment,” Marson said.

The company has been paying $76,000 annually for the four leases that are being canceled or not renewed.

Experts have said the state should increase rents for all companies that lease farmland, and should require them to disclose how much water they’re using.

Arizona currently leases about 160,000 acres of state trust land for agriculture. A large portion of the proceeds goes to funding public schools.

Fondomonte has been leasing land in Arizona for nearly a decade, much of that time during the administration of Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican. Hobbs raised the issue during her campaign last year, in which she ultimately defeated Republican Kari Lake.

Arizona Atty. Gen. Kris Mayes has also examined the land deals, and earlier this year revoked permits that would have allowed Fondomonte to drill more wells on state-owned land — in addition to eight wells that records show the company has drilled in recent years while expanding its operation.

“It has been long evident to Arizonans across our state that these leases never should have been signed in the first place,” Mayes said. “The decision by the prior administration to allow foreign corporations to stick straws in the ground and pump unlimited amounts of groundwater to export alfalfa is scandalous.”

Mayes called the governor’s action a good initial step, and long overdue.

“The failure to act sooner underscores the need for greater oversight and accountability in the management of our state’s most vital resource,” Mayes said, calling for additional steps to protect groundwater in rural areas.

Even as Arizona grapples with cuts in Colorado River water, Phoenix’s suburbs are expanding. Experts warn that desert growth based on groundwater poses risks.

In most rural areas of Arizona, groundwater remains unregulated and state law doesn’t limit well-drilling or pumping.

Groundwater levels have been dropping as large farming operations have expanded and drilled more wells, while some families have been left with dry wells and taps. State leasing of farmland adds a layer of complication to the widespread problems, with overpumping occurring on public land, facilitated by state policies.

The area of Butler Valley is one of the few groundwater basins in Arizona where water can legally be pumped and transported by canal to urban areas. The ongoing shortages on the Colorado River have heightened interest among officials in preserving that groundwater as a backup supply, said Kathleen Ferris, a researcher at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy.

“I do think that the cancellation of these leases is, in part, a response to scarcity,” Ferris said. “However, while many have expressed outrage that a foreign company has been allowed to pump Arizona groundwater to grow crops for export, the real issue is that Arizona lacks a comprehensive policy to manage groundwater supplies in rural areas. The depletion of finite groundwater in these areas by expanding industrial-scale agriculture will continue without such a policy, jeopardizing the water security of those areas.”

The governor said the state canceled one lease after Fondomonte failed, despite being told in 2016, to include “secondary containment structures” on fuel storage units on the land.

Hobbs said the State Land Department also determined that renewing the three remaining leases in Butler Valley is “not in the best interest” of the state’s beneficiaries of the leases “due to excessive amounts of water being pumped from the land — free of charge.”

Marson said the company continued to be invested in Arizona and is committed to “efficient agricultural practices.”

“Fondomonte will continue to work with Gov. Hobbs and her administration to discuss groundwater matters moving forward,” Marson said.

The desert aquifers that supply the farmland, like others in Arizona, hold water that has accumulated underground over thousands of years. State records from six wells in Butler Valley show declines in groundwater levels ranging from 2 feet to 13 feet between 2010 and 2020.

Drought and global warming have transformed the Colorado River, making some sections unrecognizable to those who have spent decades on the river.

The governor noted that the area “holds unique value” as one of five water “transportation basins” that can be tapped when needed for other parts of the state, and the only one of those that is predominantly public land.

“I think it’s a sign of great concern on the part of the state, great concern on the part of the governor, that this water is simply too valuable to be used growing alfalfa,” said Robert Glennon, a water law expert and regents professor emeritus at the University of Arizona.

He noted, however, that the United States is the world’s “foremost exporter of water in the form of farm products,” whether soybeans, wheat, corn, alfalfa or nuts.

The larger issue in Arizona, Glennon said, is the need for the state to start limiting groundwater pumping in unregulated rural areas, similar to rules that already exist in Phoenix, Tucson and other urban areas. As the situation stands, he said, in large parts of the state, “it’s still open sesame.”

“Anyone who wants can drill a well and pump as much water as you want. And that’s just the Wild West,” Glennon said. “There should be statewide rules.”

Glennon said he favors this sort of reform rather than moving toward “protectionism.”

Glennon said he also served more than a decade ago as a lawyer on a consulting team for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which was using large quantities of water to grow alfalfa.

“One of the things we said was, ‘You can’t use this fossil-age water in the kingdom. It’s just way too valuable,’ ” Glennon said. “‘You should instead go on the open market, and buy the alfalfa, the international market.’ “

He said that’s precisely the approach Saudi Arabia has taken in recent years.

Irwin said she thinks Arizona’s farmland leases have been “completely mismanaged by the state,” both by not requiring reporting of water use, and by allowing Fondomonte and other companies a discounted rate on lands where the state doesn’t pay for improvements.

“Not only were they getting a break on the leases, but that was money that was taken away from our kids’ education, which is not acceptable,” Irwin said. She said state officials “shouldn’t be giving out discounted leases to anybody, whether they’re foreign or not.”