Water concerns prompt new limits on growth in Arizona

Arizona’s governor has announced plans to limit new construction in parts of the Phoenix area after a state analysis found there isn’t enough groundwater to support all the planned growth in the coming decades.

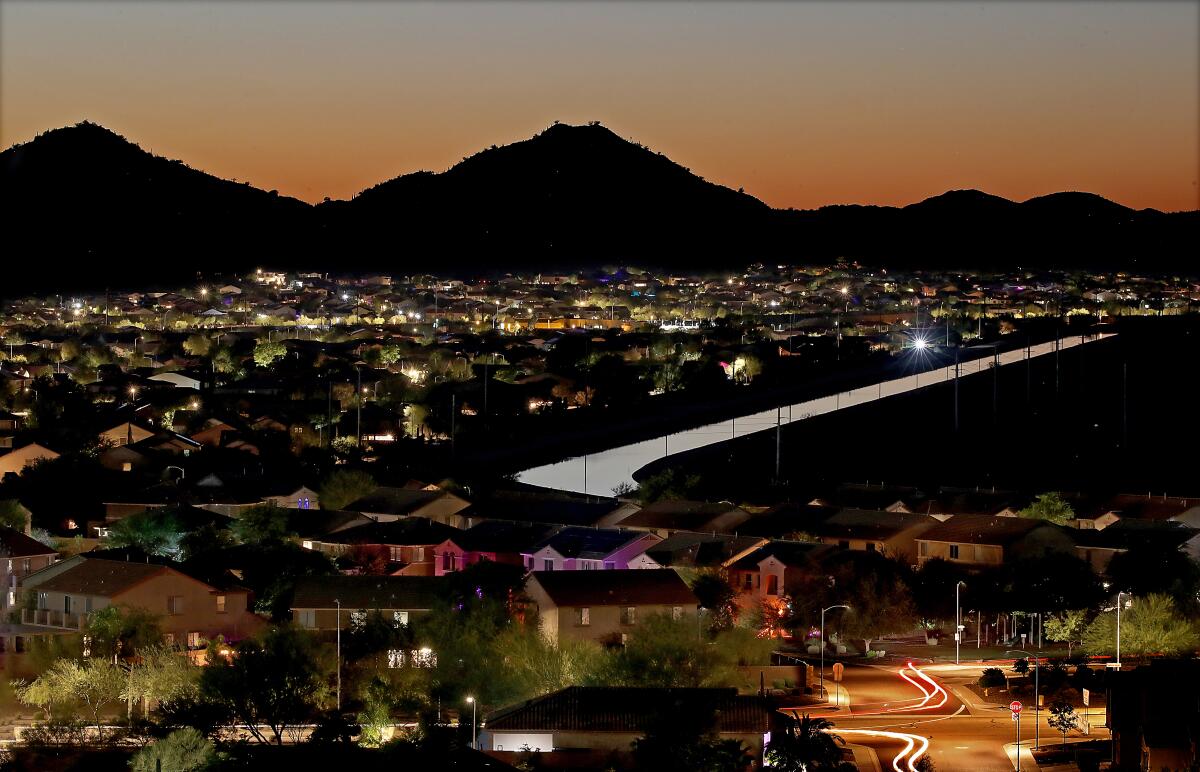

The announcement Thursday by Gov. Katie Hobbs represents a major shift for one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the country and is expected to hinder development in some suburbs that have been springing up in the desert around Phoenix.

State officials analyzed groundwater in the Phoenix area and determined that the area’s groundwater wasn’t sufficient to supply all the projected water needs over the next 100 years. As a result, Arizona water regulators plan to stop issuing approvals for new developments in areas that depend entirely on groundwater pumping.

The governor announced the results of the study by the Arizona Department of Water Resources, which found that over the next century, the Phoenix area would have some “unmet demand” for groundwater supplies.

“The results of this study show that we need to take action once again,” Hobbs said at a news conference. “If we do nothing, we could face a 4% shortfall in groundwater supplies over the next 100 years.”

The announcement comes as Arizona also deals with cuts in water supplies from the Colorado River, which is over-allocated and has been sapped by more than two decades of drought worsened by climate change.

Even as Arizona grapples with cuts in Colorado River water, Phoenix’s suburbs are expanding. Experts warn that desert growth based on groundwater poses risks.

Phoenix and surrounding cities rely on a mix of water supplies, including water from the Colorado River, the Salt and Verde rivers and water pumped from wells. In recent years, suburbs in outlying areas, such as Queen Creek, Apache Junction and Buckeye, have rapidly grown while depending largely on groundwater.

“We have to close this gap and find efficiencies for our water use, manage our aquifers wisely and increase our utilization of renewable supplies,” Hobbs said, referring to water imported from the Colorado River or other sources.

Groundwater is regulated around Phoenix, Tucson and other cities under Arizona’s 1980 groundwater management law, which requires developers to obtain water-supply approvals showing long-term water availability.

Hobbs said the state would “pause approvals of new assured water supply determinations that rely on pumping groundwater, ensuring that we don’t add to any future deficit.”

Hobbs emphasized the new limits would not affect industrial development or construction of projects that had already been granted certificates by the Department of Water Resources. She said there were about 80,000 residential lots where construction had yet to begin.

“This pause will not affect growth within any of our major cities, where robust water portfolios have been proven to cover current and future demands,” Hobbs said.

Hobbs, a Democrat who took office in January, has said she hopes to improve management of groundwater and recently created a council to consider reforms. She also recently released the results of a state analysis that showed insufficient groundwater to support planned growth in the Hassayampa area west of Phoenix, where large developments have been proposed depending primarily on groundwater.

Water experts said the governor was making an important and necessary change.

“Groundwater is really the key to long-term sustainability in desert cities like Phoenix,” said Jay Famiglietti, a hydrologist and professor in Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability. “So anything that we can do to save water moving forward becomes critically important, not just for right now, but for future generations.”

He said the governor was moving toward a comprehensive plan that also included conservation, looking for new sources of water, and exploring technological solutions and ways of improving policies.

“She’s demonstrating the kind of leadership you need under these circumstances of rapidly changing climate and decreasing groundwater availability,” Famiglietti said.

Colorado River in Crisis is a series of stories, videos and podcasts in which Los Angeles Times journalists travel throughout the river’s watershed, from the headwaters in the Rocky Mountains to the river’s dry delta in Mexico.

Kathleen Ferris, a researcher at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy, said she had been pushing for this kind of change for years.

“We’re in a situation where we can’t grow more subdivisions on groundwater,” Ferris said. “If we’re going to grow, we’re going to have to grow sustainably.”

State officials and others said the change wouldn’t stop growth.

In most cities and suburbs around Phoenix, new developments within the territories of water providers that have an approval called a designation of assured water supply will still be able to move forward. Planned subdivisions that already have a certificate of approval will also be unaffected.

In other areas, however, proposed subdivisions won’t be allowed unless developers can demonstrate a sufficient 100-year water supply that doesn’t depend on the local aquifer.

“There will be growth. But this is going to change the pattern of growth, the density of growth, and where growth will likely occur,” said Ferris, a former director of the state’s Department of Water Resources.

“We can’t continue to grow on finite groundwater. We cannot do that and live sustainably in this valley, in this desert,” Ferris said. “We have to learn to live within our means. We have to adapt and make changes.”

Leaders of business groups also voiced support for the steps by the governor and water officials. Chris Camacho, president and chief executive of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council, said that by proactively addressing these challenges, “we are demonstrating our dedication to long-term sustainability and securing Arizona’s water future.”

It isn’t the first time state officials have reassessed how much groundwater is available to serve growth. In 2019, the Department of Water Resources halted new approvals for some housing developments in Pinal County, between Phoenix and Tucson, after projections showed insufficient groundwater to meet the long-term demands.

The latest measures were adopted in response to a new groundwater model developed by the department.

The results of the model turned out to be consistent with past models and “what we more or less expected,” said Emily LoDolce, the department’s groundwater modeling section manager.

Ryan Mitchell, chief hydrologist for the department, said the projected groundwater demand may also be inflated because of the recent surge in development projects.

“There’s a lot of pumping that we have to put in the projection simulation that is above what’s been historically pumped over the last 10 or 20 years,” Mitchell said.

The current projection is based on combining past demand, which uses water records through 2021, and adding “unmet demand,” which accounts for all the water certificates issued for proposed developments — even those that end up not being constructed.

“The reason why you have to account for all of those, even if they’re not built yet, is because you have to protect the consumers living in those homes,” Mitchell said.

Under the current projection model, state officials calculated the Phoenix area would use 140 million acre-feet of groundwater in the next 100 years.

They estimated the unmet demand over that period at more than 4.8 million acre-feet. (An acre-foot is enough water to supply roughly three typical homes in the Southwest at average rates of water usage annually.)

The good news, Mitchell argues, is that demand is subject to change, and if demand decreases when the next projections are calculated, it could help close the 4% gap between projected supply and demand.

“As data changes over time — let’s say next year we have a different set of current demand usage — we can rerun the model again at that point,” Mitchell said.