From the Archives: It wasn’t in the script: Carrie Fisher interviews Steve Martin about writing

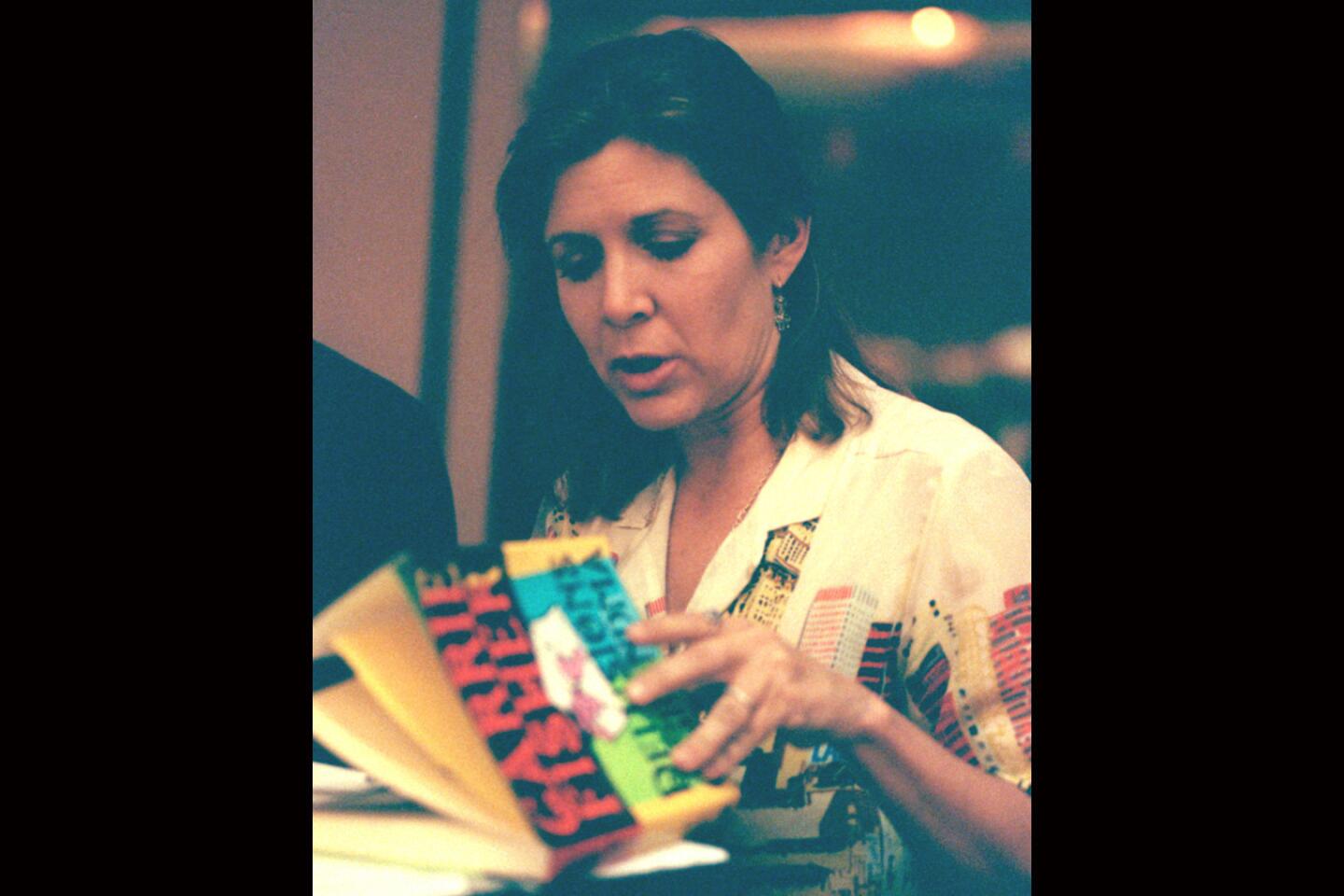

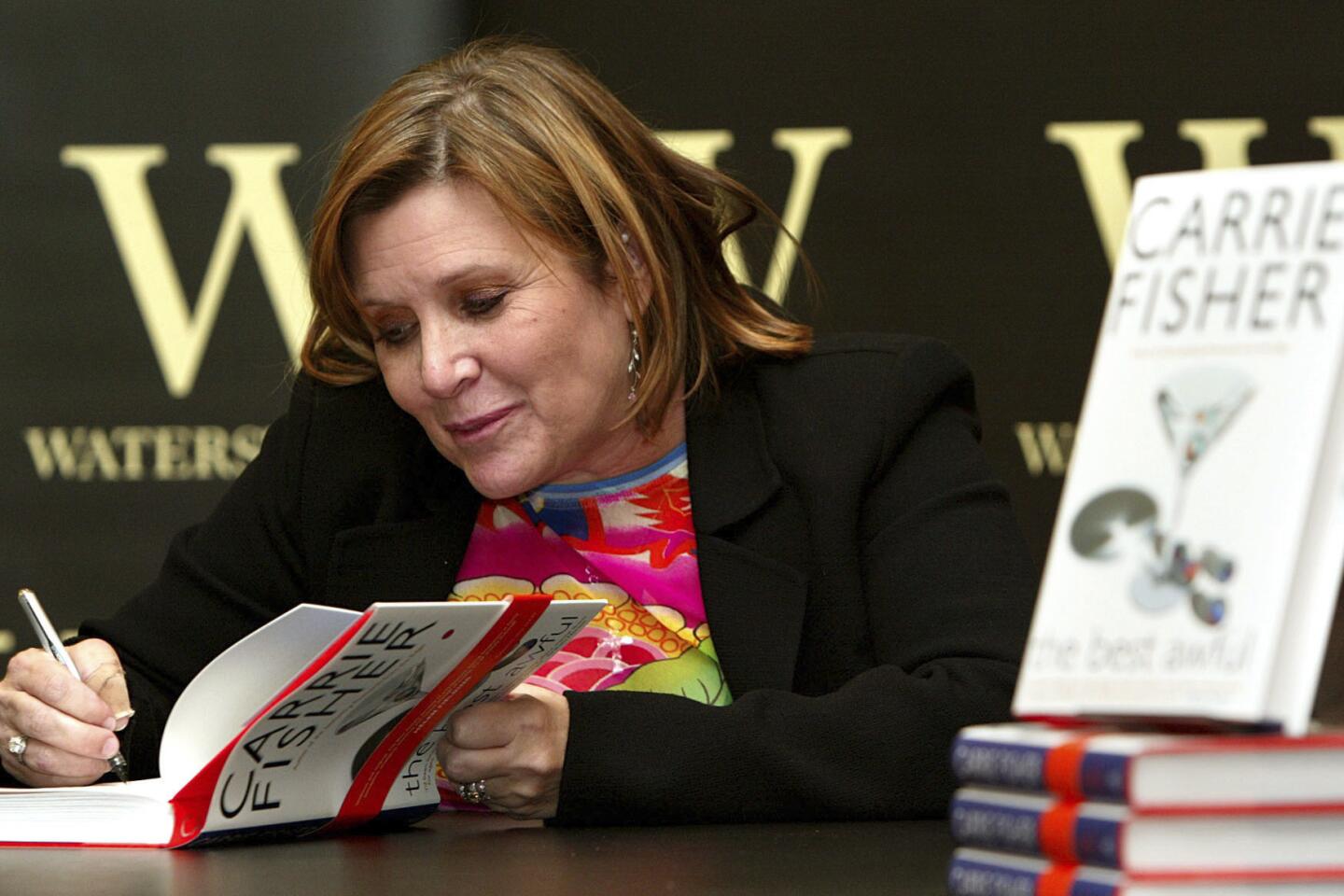

Actress and author Carrie Fisher, the child of two Hollywood icons who rose to fame as Princess Leia in the blockbuster “Star Wars” series, has died at the age of 60. Fisher interviewed fellow actor Steve Martin for The Times about his film “Bowfinger” in 1999. This story originally ran in The Los Angeles Times on July 25, 1999.

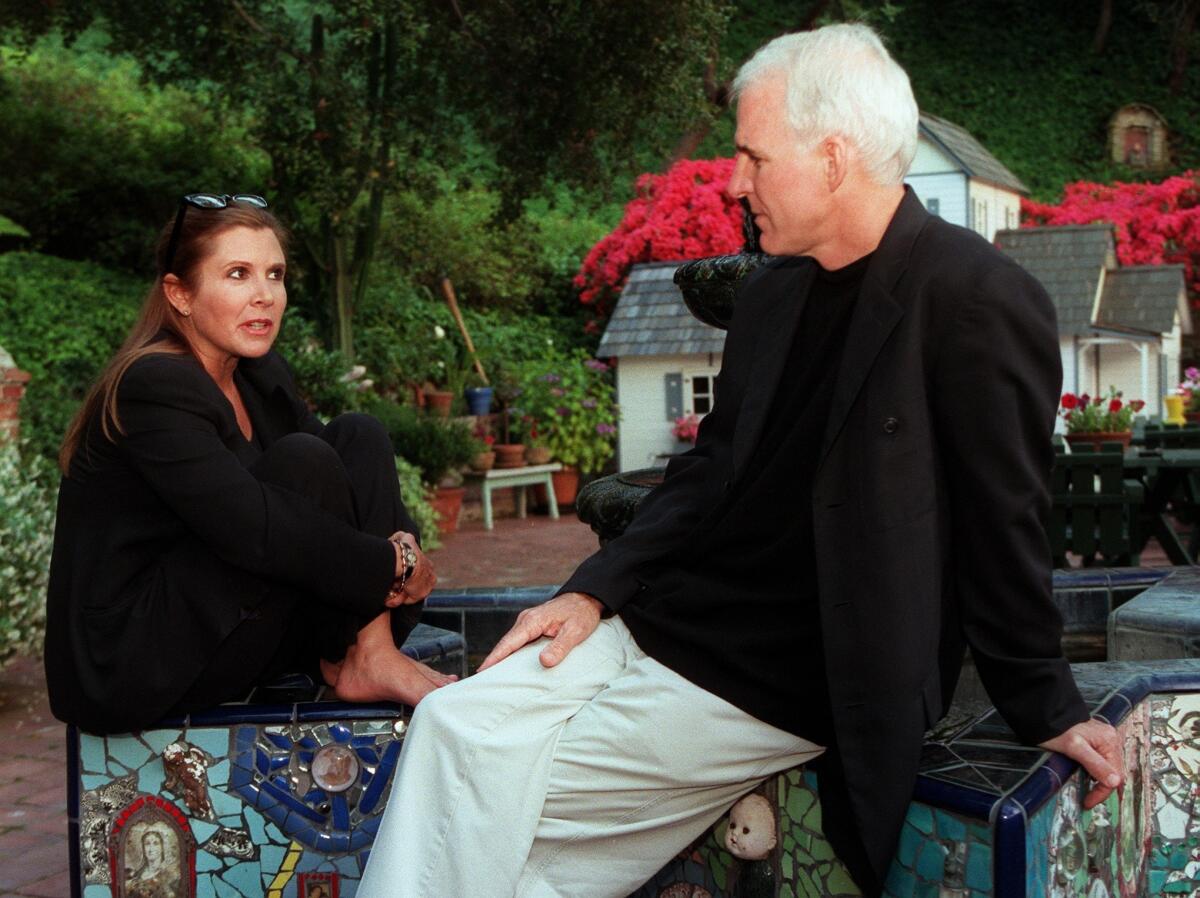

Carrie Fisher and Steve Martin share some similar traits. They’re both funny. They’re both successful writers as well as busy actors. They both know Hollywood intimately — it’s a world they both mock with affection, in scripts and novels, essays and conversation.

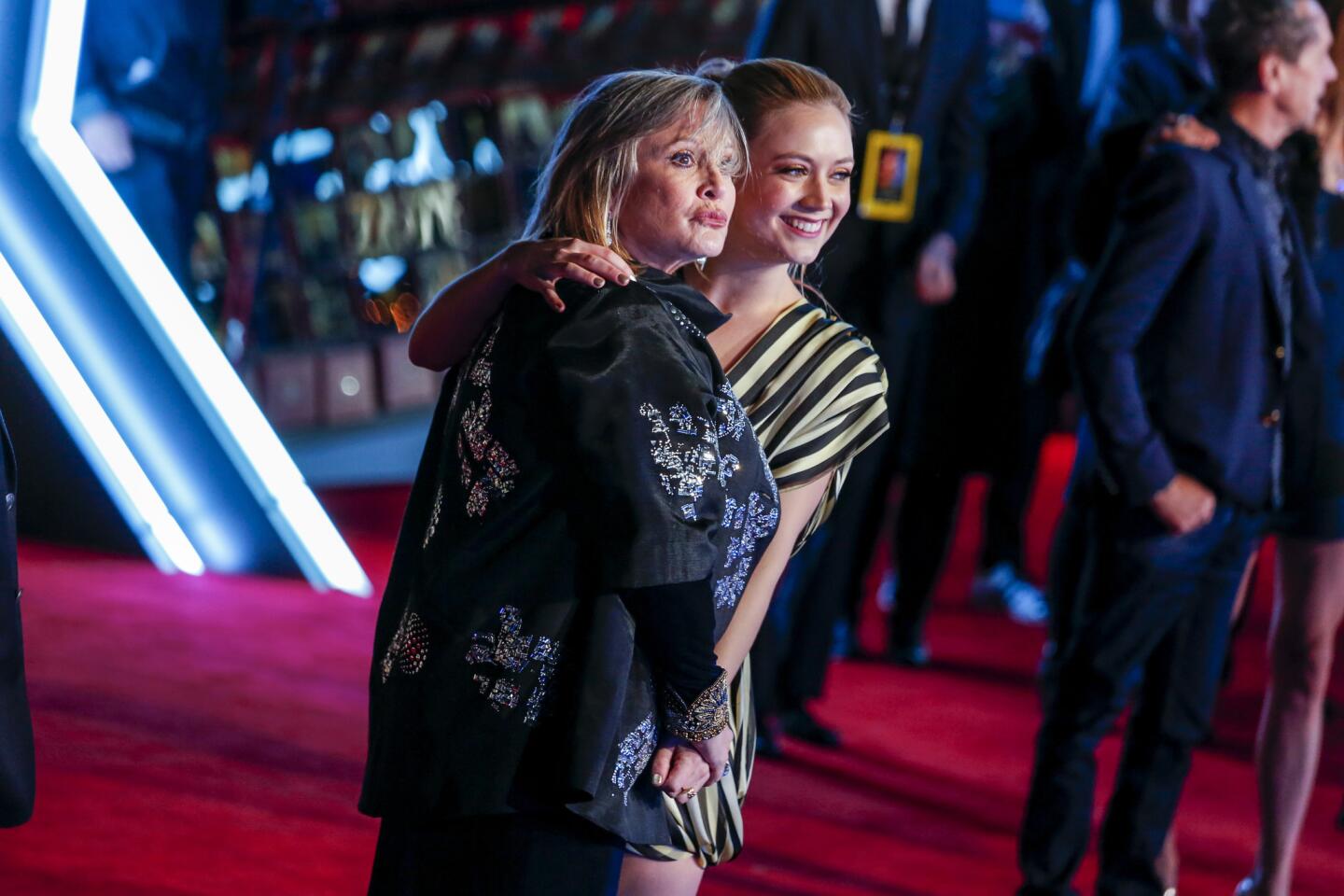

With Martin’s new film, “Bowfinger,” set to open next month, Fisher and Martin renewed their acquaintance at her Beverly Hill home and talked about the film (a sendup of action films and the industry), writing and comedy.

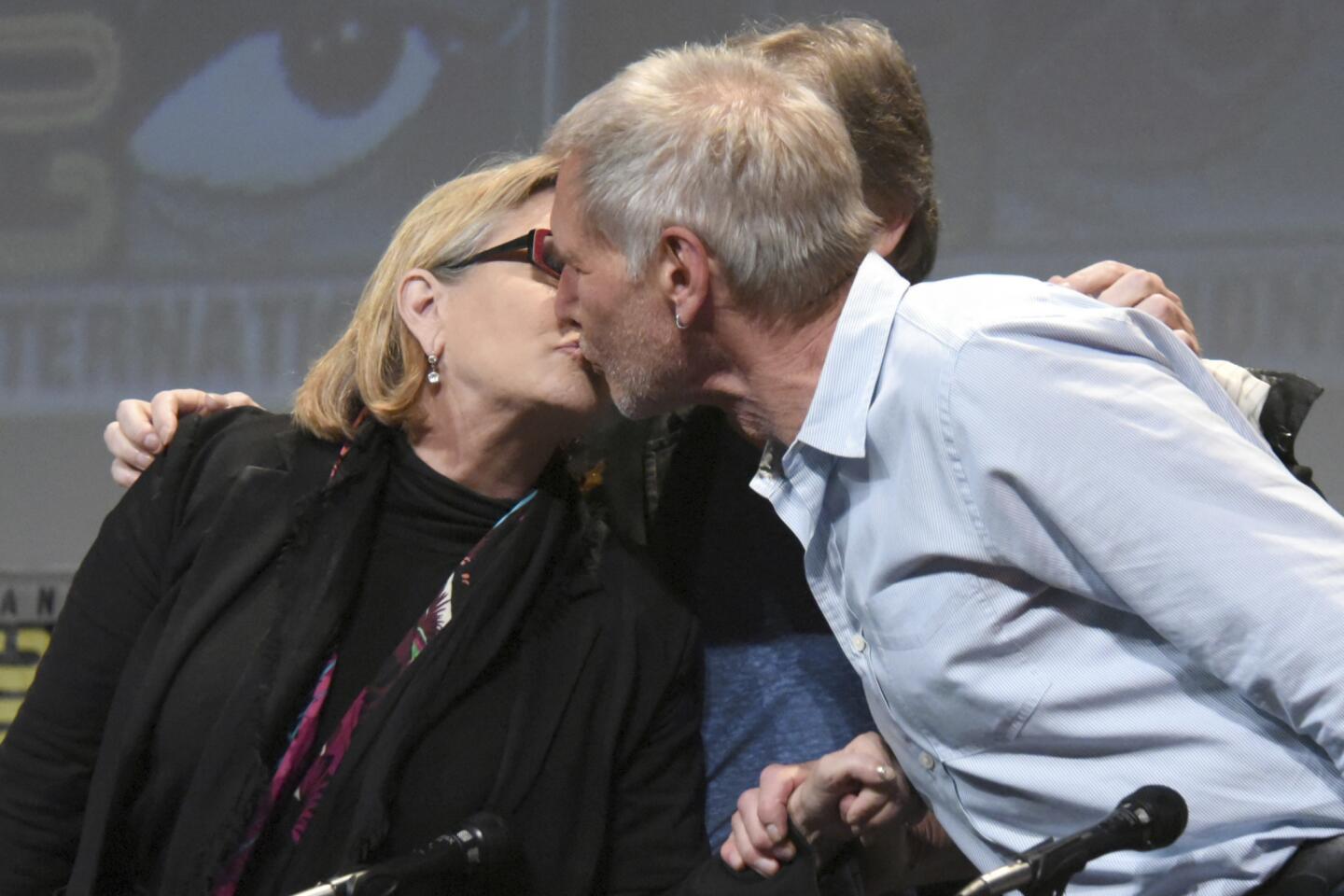

I slept with Steve Martin once and once only, 20-some years ago. And I interviewed Steve Martin once and once only, 20-some days ago. You do the math.

But I remember saying to him all that time ago that if he ever had occasion to be interviewed by the L.A. Times in future (I frequently said “in future” in those days), would he keep me in mind as the interviewer? He told me that he would, and as you see, he was as good as his word. All this is either true or not true. Like life.

But what is patently true is that Mr. Martin — yes, he makes journalists like myself call him Mr. Martin — has written another funny film, “Bowfinger.” Directed by Frank Oz, produced by Brian Grazer, written by Mr. Martin, and starring Eddie Murphy, Heather Graham and himself, the Universal Pictures film opens Aug. 13. It’s about fly-by-night filmmaker Bobby Bowfinger (Mr. Martin), who tries to make a movie with paranoid action star Kit Ramsey (Murphy), who doesn’t even know he’s in the film, with the help of a hapless crew (whose members include Graham and Christine Baranski) and clueless stand-in Jiff (also Murphy).

Steve and I spoke of how we first met (the Improv — more than 25 years ago); how I did an episode of the George Burns comedy show that he directed perhaps 15 years ago, how we both have the same lawyer and how we both had been in therapy, although we weren’t unhappy people. Steve told me, “I’m not unhappy, I’m not unhappy at all. I mean, we all have a dark side. Normal dark. If you didn’t, you wouldn’t be alive.”

Steve was born in Waco, Texas, and his family moved to California when he was 4. He has an older sister. His father sold real estate in Orange County, and his mother was a housewife. His sister went north to college, got married and raised two kids. Their 87-year-old mother is still living in Orange County. When Steve’s father realized Steve was going to be in show business, he wrote to actor Raymond Massey, whom he’d known when he was younger.

“Like Raymond Massey would be able to help me,” Steve says. “It was sweet of him, you know?”

Steve started out writing for the “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” for which he won an Emmy in 1968. He continued writing for television for Glen Campbell, Sonny & Cher and Pat Paulsen’s shows. He made two comedy albums, “Let’s Get Small” and “A Wild and Crazy Guy,” which became hits in the ‘70s. Then, he says, “I was on ‘Saturday Night Live.’ ”

Though he wrote the material for his act and for those various TV shows, he did not consider that to be the sort of writing he would come to do later on. Today, he is a produced playwright (“Picasso at the Lapin Agile”), occasional essayist (largely in the New Yorker) and author (“Pure Drivel” has spent time on many bestseller lists). It is his play, however, that he credits with changing the way he approaches writing.

Carrie Fisher: You have a career unlike anybody else. I can’t think of too many actors who write scripts, or I don’t think anyone writes plays or writes books, too.

Steve Martin: There are a few. [Chazz] Palminteri [“A Bronx Tale”]. Ben Affleck and —

CF: Oh, right — those guys. How did you decide to write your play?

SM: I had a place in New York for years, and so I’d go to the theater, and I remember that I saw a play and thought it was very funny. I thought that would be a real challenge for me. So I put two and two together and said, “What am I good at? I’m good at listening to the audience and letting the audience tell me what is funny, meaning I can edit.”

So after I wrote my play, I realized that’s half the battle — being able to stand back, listen, cut and rewrite. Then I thought I could write. I had already written some screenplays and been onstage, so I thought that was a good combination for writing a play, and I had the idea. So I started writing it.

But at the same time I was frustrated with where I was in comedy. I thought I was getting old, you know? When I performed, it felt familiar, and that’s a deadly feeling to have. And it didn’t feel funny like it’s supposed to feel. I can remember when I was doing stand-up, I thought . . . “I feel funny. I’m not necessarily saying anything funny, but I feel funny.” And I had that feeling in movies for a while too.

But there was something happening. “I’m going to change something,” I thought. “Maybe I’ll have a salon, you know, and we’ll talk about comedy!” Stupid idea, but I was thinking those kinds of thoughts because something had to change. Looking back, I realized I was already doing the things that changed my life, like writing my play; that was the thing that was going to change my life.

CF: I think people know you best as the actor, unaware of your talent and fondness for writing. What is it about writing for you?

SM: With writing, you purge something out of yourself. You tell a story that you’ve been carrying around in your head, and you know the story.

CF: All writing is cathartic.

SM: Yeah, I’m sure.

CF: Don’t you think? It’s very cathartic for me when I can write about whatever’s happened. I’m a warhorse; if I have a situation that’s bad, I can handle it. But I can handle it best when I joke about it. That’s my writing. When you take a story in hand and it becomes yours, no matter whether you’re telling something for true or you’re telling another sort of story — you’re the narrator. There’s something that becomes very clean about your voice. Did you find that with writing this movie?

SM: Yeah, but as you know, books and screenplays are different. With books, you’re writing what’s the truth, unlike screenplays, where a lot of times you’re writing what you think will work. When I wrote my play and my book, I thought, “That’s the feeling I want to have when I write. Why can’t I have that feeling when I write a scene?”

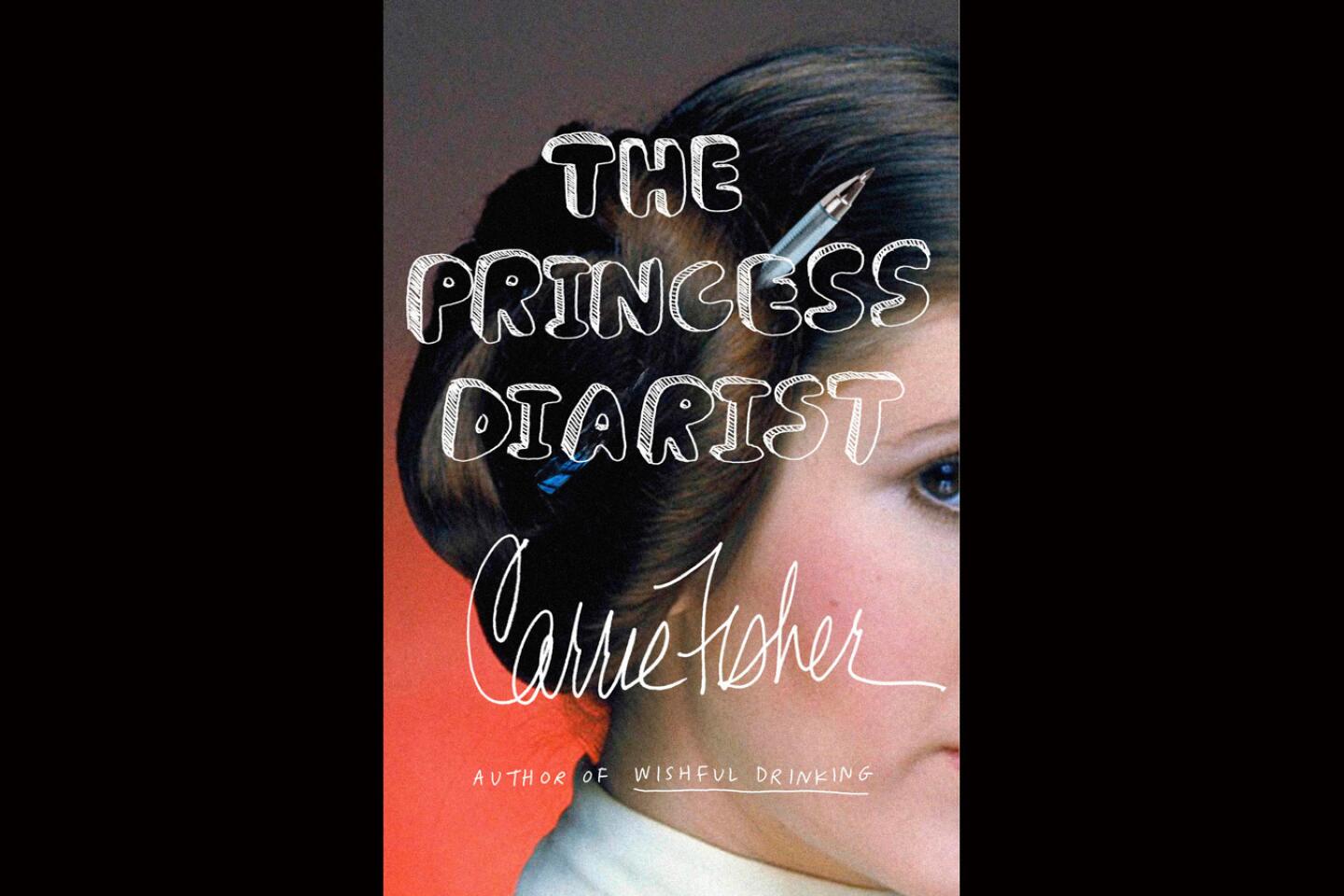

CF: Writing my book [“Postcards From the Edge”] changed my life completely. But you had more control to begin with; you had a comedy act.

SM: Yeah, I did have more control, but control wasn’t the point. It was like what I was writing was different.

CF: And what you’re proud of takes on more weight. Now you’ve written this hilarious movie, “Bowfinger.” There’s a joyful playfulness in it. It’s such a funny idea that’s executed really well.

SM: Well, I find that when you have an idea you have to stop yourself and think ahead and go, “Are there scenes? Are there scenes to be written that are going to be funny or is it just like that and there’s nothing going to happen?”

CF: There’s a big difference between when you hear about something and you say, “Well, that is a sketch. It’s not a whole thing.”

SM: Uh-huh. I’ve had several people tell me that plotting is, “Oh, that’s just work.” They [write] the fun creative part, the dialogue on it, then they go to the plot, it’s just work. They have to work at it.

CF: But I think the whole thing is called work.

SM: Yeah. But sometimes it’s not work.

CF: And sometimes it really is, but every so often when it’s a pleasure is why you do the work. How do you feel about the film now?

SM: Well, I’m proud of it, and it was a struggle. You know, it’s show business. I’ve had this experience, like, three or four times in my life where there’s such a high, and an hour later it would be so low. Your hopes and dreams ride on a movie, and I’m not just talking about box office. I’m talking about audience. One bad screening and you’re just killed.

Early on, we had a very bad screening. The problem was they forgot to throw the Dolby switch, so you could only pick up, like, every third word. It was a nightmare, I wanted to kill myself because I knew it wasn’t the film, it was the Dolby switch. Then a part of me is going, “I hate myself, why did I ever do this?”

Then we had the problem fixed, and it was, like, a miracle. An extreme response, a big change.

You know, I wanted a movie that would play well in Europe. Very physical comedy. And the biggest challenge in physical comedy, most importantly, is not to become too stupid, but for it to be clever, because otherwise you’re just falling down. I was talking to Frank Oz about this. He said, “We can’t just have the ladder whack somebody. We’ve got to have the ladder whack somebody because of X, Y and Z having been set up, and it’s inevitable the ladder is whacking us.”

CF: How did you get the idea?

SM: It’s hard for me to remember. But I’ve had it for a long time — I’d say over 15 years.

CF: Wow.

SM: Well, I had the story but not the ending. I was going to write another story and mesh the two together. The other story was about this big Hollywood producer who finds out he has two months to live.

CF: So there were two ideas?

SM: Yes, two ideas that I meshed together. The second idea was about this huge Hollywood producer who goes to his window and says to himself, “I’ve had a great life, a great career, and when I’m gone the other producers will go on, and they’re my friends and they’ll make movies,” and then he pauses and thinks: Why should he be the only one to die? So he decides to throw a party and invite everyone in Hollywood and blow up his house.

CF: (Laughing.) Nice. I see.

SM: And so, these two stories are about these people who were making a movie and this other thing was going on, and the ending of the movie was, you know, the party, because we’re dying to get to the party scene in the film because every celebrity in Hollywood is supposed to be there. So we get in, we’re shooting around the scene, and, meanwhile, the bombs are underneath the house ticking away. And then we go outside to get a master shot of the house, and then it blows up. All these bodies go flying all over the screen and everything. And the ending finishes at the Oscars, where there’s, like, 18 people there. (Laughs.)

So everyone is dead, and you know, Kit Ramsey [the action star played by Murphy] wins the Oscar for his best performance ever. But I really didn’t like that ending because I thought it was too much of a black comedy, and I wanted it to be more of a big, funny physical comedy. So then I realized that I had to cut out the one story of the party and make the initial story more simple. Otherwise, there were just too many things going on.

And I can do the other movie sometime, you know. Something was keeping me from writing when the two stories were together, and then I realized I had to eliminate the second story to make it work.

CF: And then how long did it take you to finish?

SM: Well, the original first draft, probably two months. But you know, I always write first drafts very sketchily. I’m an anxious writer. And I don’t like to outline a story because I don’t want to know where I’m going.

CF: Really? So you follow the character then.

SM: Follow the characters and also have a general idea, but the best ideas are the ones that come up while you’re writing it.

CF: So then you finished the draft and what happened?

SM: Well, so I have the draft, and I’m all nervous about it and everything. I can’t remember if I sent it to a friend or not — I probably did. And then I called [producer] Brian Grazer. I told him I had this script I wrote, and I’m nervous about calling him because I don’t want to put him in a spot because he’s a friend. But I also felt lousy about offering it to someone else, and then it turns out he wanted it. So I gave it to him, and he read the script and said he really liked it and wanted to do it.

And I said, “Well, there’s a few ways to do this movie. Low budget, high budget or normal budget.” They thought about it for a couple days and came back and said they wanted to do it high budget! (Laughs.)

CF: Meaning Eddie Murphy and everything.

SM: I guess so, that and Frank Oz directing. But remember, I didn’t write the movie with Eddie Murphy in mind; it was Brian’s idea to give the role to Eddie. He asked if I would be interested in Eddie Murphy, and I was, of course. I had to rewrite a whole character arc with Eddie in mind.

CF: So did you have a great time working with him?

SM: Yeah, I had as good of a time as you would with someone you know is better than you. So many times, Eddie would do something, and as a writer, I would be saying . . . , “Thank you, thank you.” As the writer, I’m going, “Thanks for making that scene work.”

CF: Besides playing Kit Ramsey, Murphy plays Jiff, a nerdy guy. Who came up with the idea to have him wear braces on his teeth?

SM: Eddie.

CF: What about editing, how involved did you get?

SM: Well, Frank is extremely open and generous, but I’m not in the editing room or anything. I attended screenings and would give notes. I am proud of it, I really am. No matter what, I know I’ve listened to the audience. I double over in laughter at certain moments in the film, and I watched the heads in the audience go up and down with laughter. It’s just the greatest feeling in the world.

CF: Is this the best thing you’ve done?

SM: Um, well, I don’t know about that, because I have affection for “Roxanne” and “L.A. Story.”

CF: I know. Those are great.

SM: And “The Jerk” too, you know.

CF: And this is just —

SM: This to me is the movie I was supposed to make.

CF: You know, in person, you’re not a real extrovert.

SM: No. No. But I can be funny. People think I’m not, but I can be.

CF: I know you’re funny. I mean, I communicate with you as though you are, and I don’t do that with everybody. But you don’t work hard at it. Danny Aykroyd also had that. That’s why you guys do characters so well, both of you.

SM: I’m not really a character guy.

CF: He really is.

SM: Danny is brilliant.

CF: But in all the time I’ve known you —

SM: I don’t do characters, is that what you’re going to say? Or —

CF: You don’t do shtick, you know, like Robin [Williams] or even Albert [Brooks] does in his anxiety. I guess it’s kind of an anxiety thing. How do you describe your psychology then? That’s where I think a lot of comedy comes out of.

SM: Well, I just call it “walk speed.”

CF: Who do you admire, then, of writers, novelists and stuff?

SM: Well, start with my business, and I definitely admire Woody Allen.

CF: What prose do you like?

SM: Martin Amis. I love him. Have you ever read Martin Amis?

CF: I’ve read one. I’ve read it because through friends I had dinner with him and he was pumping me for information on lithium, which I don’t know a lot about, but he’s putting a character in a book that overdosed on lithium.

CF: Do you have panic attacks?

SM: Yeah, yeah . . .

CF: I’ve had two.

SM: I used to have them. It’s horrible. And by the way, it started when I was 21. It was fear, the same reaction you get if you were faced with a lion, only there’s no lion. It is something inside of you that you are afraid of. Then I started thinking, “Well, what is that?” Then I figured it out.

CF: What?

SM: Well, at the time I was 21, I was writing for a network television show, and I really didn’t know how to write.

CF: Do you ever? I mean, do you know you have more experience in doing? The best time I had writing was when I didn’t know how to write. I didn’t have a deadline, though.

SM: Yeah, but I was on network television. It’s a whole different thing. It’s like, if I blow this . . .

CF: That’s your whole paycheck.

SM: It’s your whole life. And then it started to subside.

CF: So are you trying to write more stuff or are you just going to —

SM: Take a break. I’m pushing myself in that direction.

CF: Do you think you’ll write another book?

SM: Oh, yeah, I’m writing a novella now, and I’ll definitely write another book. I’ve done funny books.

CF: Yeah, I know, I read the last one in rehab.

My daughter came in at this point with the intention of abducting me back into my life. It was then that Steve did these amazing card tricks. Billie was very impressed. A guy who’ll write a funny movie — well, more than one — and then to have that same guy do card tricks for your 7-year-old — well, you gotta love a guy like that.

By the way, this interview will be the last in the series I did in my upcoming book, titled “Famous Men I Have Slept With So I Could Interview Them Later,” due out in the fall for Simon & Schuster.

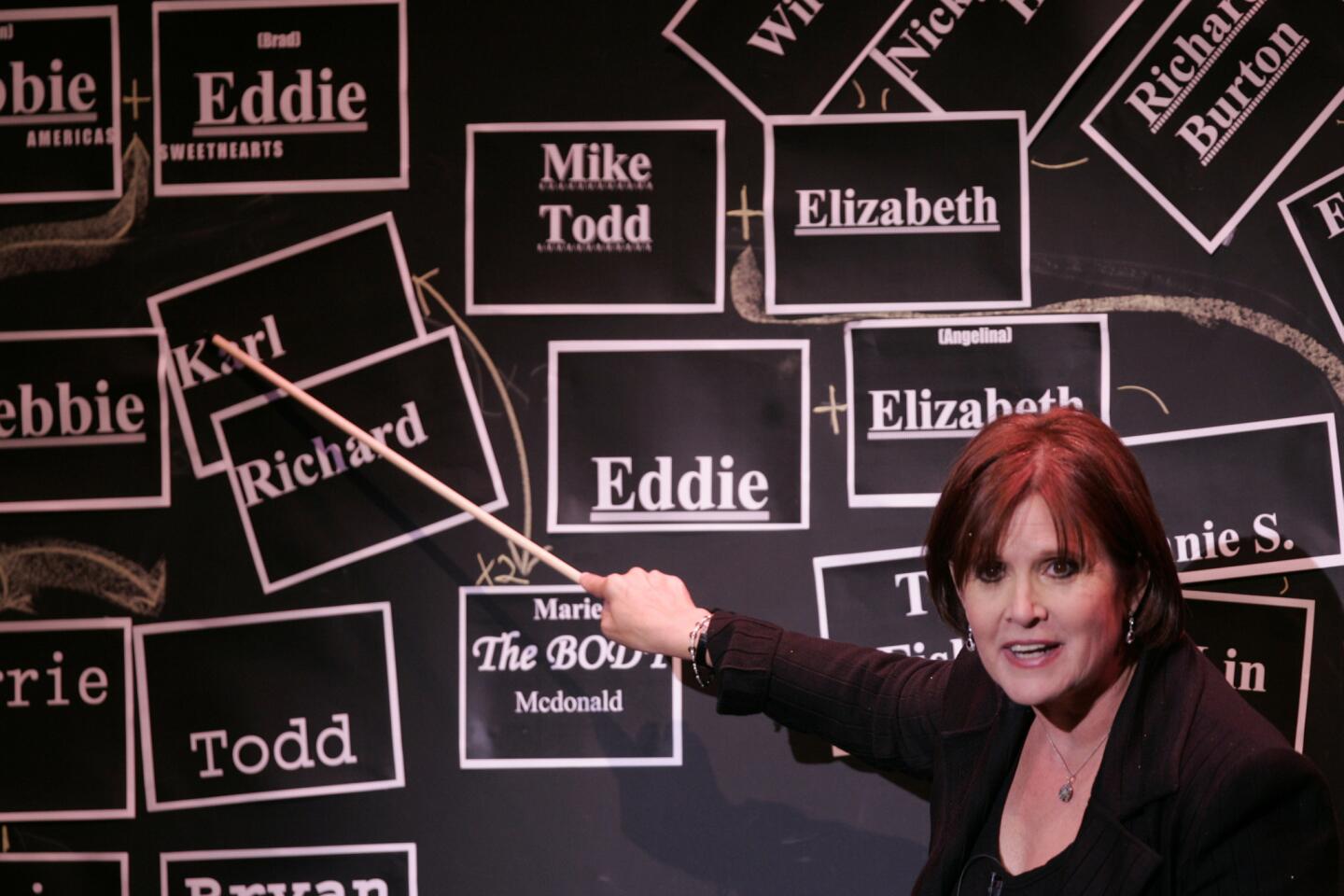

Carrie Fisher is an actress, screenwriter and novelist. She has co-written, with Elaine Pope, “These Old Broads,” an original comedy screenplay for her mother (Debbie Reynolds), Elizabeth Taylor, Shirley MacLaine and Lauren Bacall. (Her father, Eddie Fisher, will probably not be doing the theme song.) A well-known Hollywood script doctor and author of three novels, she continues to work on current movie projects and hopes to complete her fourth work of fiction soon.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.