Q&A: Nick Park is back in the stop-motion animation game with ‘Early Man’

Nick Park has won four Oscars — one more than Meryl Streep, but his characters never wear Prada. His best-known creations are the addlepated, cheese-loving inventor Wallace, and Gromit, his patient, intelligent dog. Park’s work helped to spark the blossoming of stop-motion animation, a technique Americans once associated with “Gumby,” “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” and special effects in monster movies.

Audiences roared with laughter when the Brazilian jaguar in “Creature Comforts” threw his forepaws in the air and complained that in his London zoo enclosure, he didn’t have “espace!” For the first time, a Plasticine character moved in ways that defined his personality. The animation was so polished, it rivaled the best drawn work.

Park pushed the envelope further in “The Wrong Trousers.” When Gromit looked up from his knitting at the hilariously sinister penguin Feathers McGraw, viewers believed a dog sculpted out of clay was actually thinking. Park is an exceptional director, as well as a master animator. Danny Boyle praised the model railroad chase in “Wrong Trousers” as “one of the greatest action sequences I've ever seen.”

In addition to three more Wallace and Gromit shorts, Park directed “Chicken Run” and the Wallace and Gromit feature “The Curse of the Were-Rabbit” -- all for the British studio Aardman Animation. And though it took 10 years for him to return to the director’s chair, his latest film, “Early Man,” is a longtime passion project.

The film, which opens Friday, centers on a caveman named Dug and his Stone Age tribe, whose peaceful existence is threatened by effete Bronze Age warriors with Monty Python French accents. The only way Dug can save his valley home is by beating the newcomers at a game his ancestors invented centuries earlier and forgot: soccer.

A shy, soft-spoken man, Park punctuates his words with lively imitations of his characters and the actors who voice them. He talked about “Early Man” on a recent visit to Los Angeles.

What was the genesis of “Early Man”?

I was looking for an Aardman-type approach to a caveman movie; I sketched a caveman with the club hitting a rock, and that started me thinking about a caveman having a go at sports. The English claim to have invented soccer, but we can never win at it. So that self-deprecating joke is in the story: Dug finds out his ancestors invented the game, then he learns they were lousy at it.

Dug and his tribe aren’t exactly the sharpest flints in the cave. Is it a problem to make dim characters sympathetic?

For me the more stupid the characters are, the more appealing they become. Creating these ridiculous lunkhead cavemen was part of the appeal: Dug and his band are really an extension of Wallace. I envisioned them immediately.

How did you cast Eddie Redmayne as the voice of Dug?

As we’re writing and building the clay mock-ups of the characters, we’re looking out and listening out for people, watching all kinds of movies, wondering who exactly would fit. There was a short list for Dug. When Eddie came in, he was very self-deprecating. He asked how old Dug was, and I said, ‘He’s about 15.’ Right in front of the microphone, Eddie transformed into a disheveled, awkward teenager. (Park imitates his posture.) I knew we’d got him.

Peter Sallis, the voice of Wallace, passed away last year. Will it be possible to continue the character’s adventures without him?

Obviously, how to fill those shoes is an issue: He was a fantastic performer, with such an individual, unique quality. It’s going to be an issue because I have more Wallace and Gromit ideas that I’d love to do.

“Early Man” is the first feature you’ve made without a co-director: What challenges did that pose?

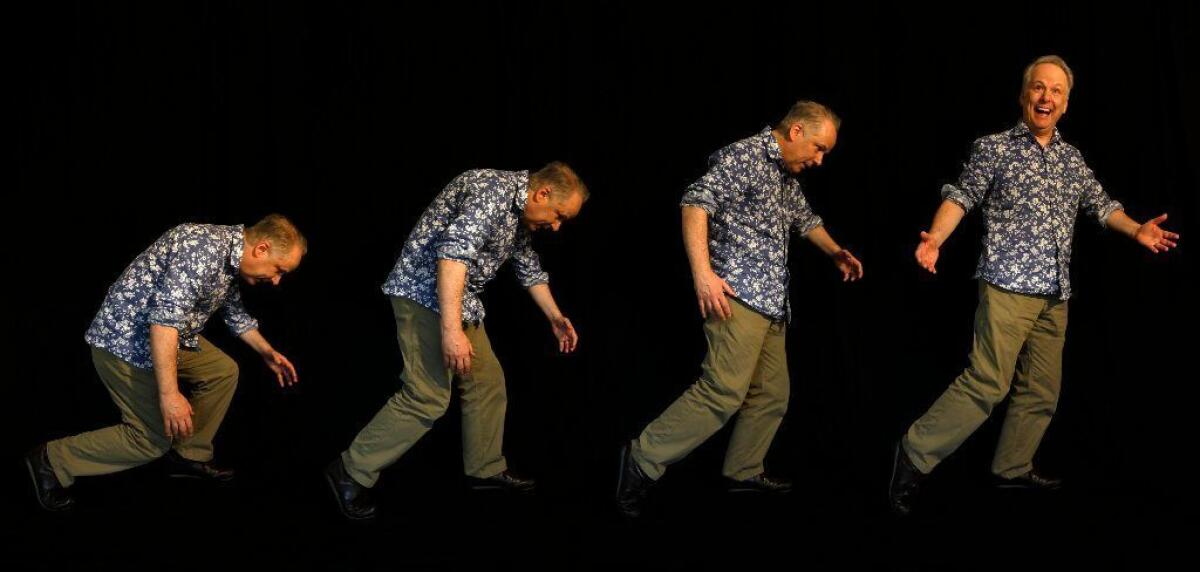

I learned a lot working with Pete Lord and Steve Box, and I enjoyed it, but I felt like holding the reins more this time. I had Will Becher and Merlin Crossingham as animation directors, and we all think the same way. To convey what I wanted from the animators, I would get in front of a video camera and act through the way I saw the scene and the characters behaving. I don’t want to blow my own trumpet, but I think I’m good at acting.

The film opens with an old-fashioned, ’50s-style dinosaur fight.

It was very much a tribute to Ray Harryhausen and “One Million Years B.C.” That film inspired me to take a Super 8 camera and start making movies. We shot the scene on digital cameras, and it was immaculate. Then we had to degrade the footage to make it look like it was from 1966. It seemed criminal to do, because the original looked so magnificent.

Stop-motion animation has come into its own in recent years.

For a long time, stop-motion was a kind of cottage industry for kids’ TV and commercials. Until “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” stop-motion was never really seen as a medium for feature films. Industrializing the process for “Chicken Run” was an issue for us; how to make a film on the scale of a Disney cartoon with that large a workforce. People wondered whether stop-frame animation with clay would even stand up to scrutiny on the big screen. With “Chicken Run,” we realized it actually stands up quite well.

The world of “Early Man” is a very stylized, cartoony one, unlike the detailed realism in many recent CG features.

I remember seeing a documentary in the ’70s about the latest work in CG in California, and the narrator said, “The pursuit of reality is a worthy goal.” Even as a student, I thought, “Why? What makes that a worthy goal?” I’m not interested in reality: that’s why I became an animator.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.