From the Archives: In Praise of Silliness: Los Angeles’ own Groundlings are celebrating two decades of, well, just plain silliness

The Groundlings’ founder, Gary Austin, died April 1. He was 75. On the 20th anniversary of the improv group in 1994, The Times’ Lawrence Christon talked with Austin and others as he took a look at the history of the comedic troupe.

Who would’ve thought that any performing group could gain in stitutional longevity by living on the fly? But when the Groundlingsthrow open their Melrose Avenue doors Monday, they begin several straight days of partying to the theme of 20 years of risky business in that most perishable of forms, improvisational comedy.

Twenty years of organized silliness on the high wire of making it up as you go along. As an exploratory form, improv is an ideal discovery process for catching the surreptitious breath of the id. In private rehearsal, it’s the hand that works its way inside the glove of plausible character. But to do it in public invites free fall. There’s no script, no erasies. And to make it funny is harder still.

Yet the Groundlings remain, as Bill Steinkellner puts it, “the Lexus of improv groups.” Steinkellner, along with his wife, Cheri Eichen, is one of numerous alumni who’ve graduated into successful careers as performers or TV writers (they worked as executive producers on “Cheers” and “Bob”). But publicly he is remembered, among other things, as the string-bean swami impaneled onstage somewhere between that nice lady from Wisconsin whose son has been whisked away by aliens from outer space, and that dark, ghoulish figure who makes a living writing suicide notes for the stars.

The improvs vanish, the characters remain. Who can forget John Paragon’s sendup of the oily Latino balladeer Ramon Azteca? Or the way Jim Jackman’s animatronic Disney Lincoln winds down in a gruesome panoply of dysfunctional weirdness? Tim Stack’s “On the Road With Guy DiSimone” prefigured Bill Murray’s unctuous lounge singer, and probably made life hell for at least one Frank Sinatra impersonator.

It was at the Groundling Theatre where Julia Sweeney developed the pathologically shy office accountant Mea Culpa before she came up with the paunchy androgynous Pat (now a movie as well as TV star), whose voice is the sonic equivalent of drool (Pat’s photograph is mounted on the door of both the men’s and women’s restrooms at the Groundling Theatre).

Paul Reubens made a career out of Pee-wee Herman; his Groundlings pals lament not only his self-destruction in that Florida porn house but his closetful of other brilliantly realized characters the world may now never see.

And it was on the strength of Phil Hartman’s Chandleresque Chick Hazard that the Groundlings were tapped to represent Los Angeles in the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival — no small feat, going head to head against the likes of the Royal Shakespeare Company, Ariane Mnouchkine’s Theatre du Soleil and Giorgio Strehler’s Piccolo Teatro di Milano. (L.A. theater never survived the foreign onslaught; of the nine local festival entries, only three are still around: the Mark Taper, the Odyssey Theater Ensemble and the Groundlings, who began at the Cellar Theater in 1972.)

But Hartman, who was still holding on to his semi-reclusive day job as a graphics designer at the time, had already brought any number of vivid characters to life, including the mythic sci-fi figure Light Man (“I can read your thoughts; I am reading your thoughts right now”) and the international talk-show host Gunther Johann, who at the mention of certain volatile topics, like the defeat of heavyweight Max Schmeling by Joe Louis, couldn’t suppress an icy Gruppenfuehrer rage.

“The Groundlings has always been a forum for evolving talent,” says Hartman, who joined in 1974. “Once you learn improv, you realize there’s a mechanism in you that you can trust, a flash that translates into character or something on a printed page. You’re never frightened again. I know a lot of movie stars have turned down appearances on `Saturday Night Live’ because they’re frightened.”

Laraine Newman, Jon Lovitz, Phyllis Katz, Edie McClurg, Cassandra (“Elvira”) Peterson, Helen Hunt, Maureen McGovern and B. J. Ward are among other performers who either started with the Groundlings or stopped in on their way to larger careers, a number of them on TV’s “Saturday Night Live.”

But as Tracy Newman, one of the troupe’s earliest members, observes: “People join to become successful as performers, but the skill you learn is writing, rewriting and editing, though you don’t know it at the time.” (Newman, who is Laraine’s older sister, also wrote for “Cheers” and “Bob,” as well as “The Nanny.”)

To that end, nearly 40 writers or writer-producers have gone on to movies and TV; they include Marcy Carsey, Don Siegle, Rob Gaines, Robin Schiff and George McGrath. Conan O’Brien was an almost-Groundling; he was about to come on board when “The Simpsons” beckoned. Ditto with Jeffrey Abrams, who was about to join but went on to write “Regarding Henry” and “Forever Young” instead.

Some people, like actor Craig T. Nelson, didn’t stay long. Comedian Richard Lewis was too full of New York high anxiety to go on-before he realized that New York high anxiety was his act. Some showed up and didn’t stay at all. Harrison Ford got a movie before he started his first class. Kevin Costner took a look around and told director Tracy Newman that he wasn’t cut out for this-he could never operate outside the safety zone of a script. “That was a rare confession, for an actor,” Newman says.

*

Party time for all this week doesn’t hide murmurs of discontent, however, or skepticism, regret, memories of pain, concern that the Groundlings aren’t as good as they once were, or anxious questions about the future.

How is it that the troupe is solidly ensconced in one of the trendiest spots in the nation, with a $500,000 annual operating budget, yet its performers still don’t get paid? Why haven’t the Groundlings, despite an illustrious roster, become a breakout success like the SCTV ensemble? Why can’t the organization cut its own TV and movie deals as a production entity, particularly when a reported $10,000 rent falls monthly onto the company budget like a safe out of a skyscraper window.

Part of the beefs are a natural byproduct of the growing pains and unavoidable internal strife that accompany the volatile and even eccentric business of creating the new. Not everybody gets onstage every night. Not everybody makes the cut through the various tiers that make up a Groundling’s progress from improv class to the main company.

Some people believe that the structure of the organization, in which every member of the company has an equal vote in things, is inherently self-destructive. The memory of how the group once sabotaged a lucrative contract with “The Merv Griffin Show” in 1976 is still fresh in some people’s minds.

“You want to put new wallpaper in the ladies’ room, 30 people have an opinion on what it should be, and nothing gets done,” says Deanna Oliver, a onetime Groundlings performer who is now revue director and head coach. “It’s pure socialism. I don’t know how the company survives. Actually, it doesn’t. It goes bankrupt every five years.”

Too, the drain of competing in a perpetual on-your-toes format can have a brutal effect on one’s quotidian life, especially considering the wispiness of the actor’s ego.

“I was one of the first people here, before we moved onto Melrose, and I can tell you that there was not one relationship that came to the group that survived it,” Tracy Newman says. “Every marriage, every relationship, broke up. Of course, a lot of people took up with each other too.”

The Steinkellners, who met at the Groundling Theatre and now have two young children, were among the latter.

“Everybody dissolved, but a lot of people found themselves back together mixed and matched,” Cheri Eichen says.

“There were some whoppers,” adds Bill Steinkellner. “There’s nothing like a split-up in the middle of a theater group.” His eyes seemed to dance with memories of Carthaginian knock-down drag-outs that will never be told.

*

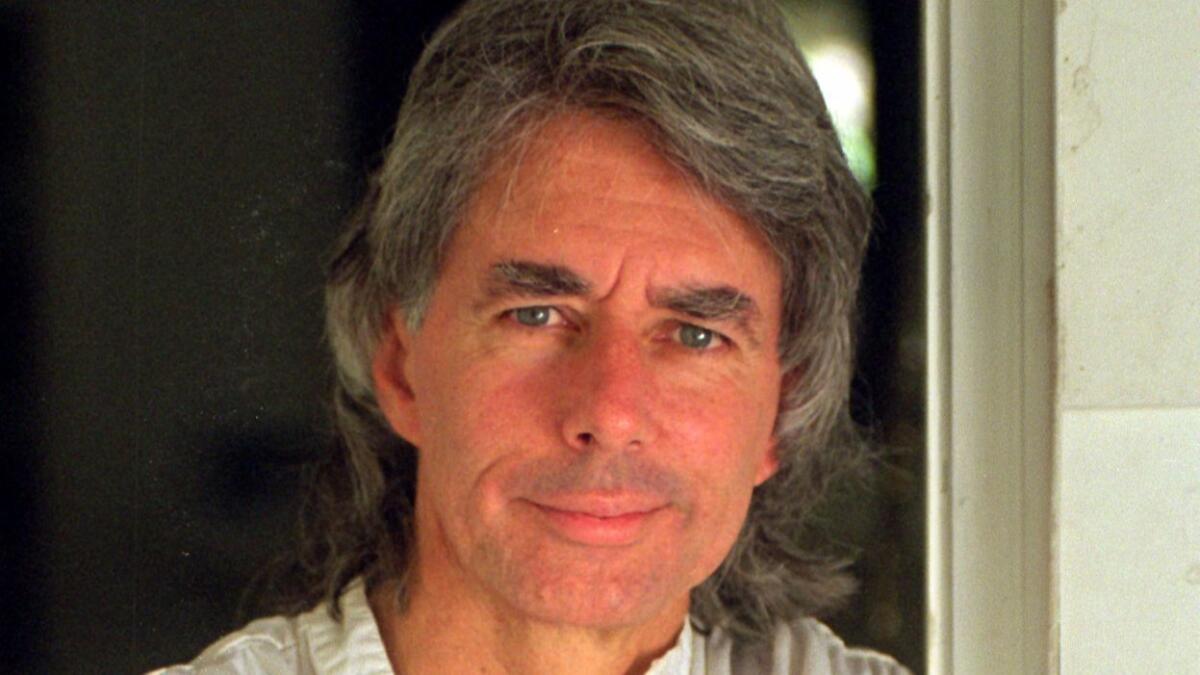

The story of the Groundlings, like that of many arts groups regardless of how grand they become, is largely the story of one man. At 52, Gary Austin has the ethereal pallor and slender build of an itinerant troubadour (he’s a longtime country singer). But his slightness seems charged by a small filament of incandescent energy. Born in Oklahoma and raised in and around the oil fields of Odessa and Corpus Christi, Tex. (“horrible, desolate places”), he grew up in what he terms “the environment of the Nazarene Church,” whose flinty spiritual severity drove him into years of therapy but whose music and preaching grandiloquence eventually led him to the theater.

He had the rare good luck to be at San Francisco State the same time Jules Irving and Herbert Blau were there-two innovative theoreticians and directors whose influence still radiates through the American theater. Classmates Martin Benson and David Emmes co-founded the Tony Award-winning South Coast Repertory; Austin planned to join them but never got south of Los Angeles.

“I had a friend from San Francisco’s Committee who took me over to the Tiffany on Sunset one night to see the company’s L.A. chapter,” Austin says. “They were doing improv. Rob Reiner was in the cast. I was blown away. I’d never seen anything like it. I joined their workshop, for $1 a night. Ellen Burstyn and Penny Marshall would come in. I never felt so comfortable in my life, and learned a lot about the relationship between actors and audience by running lights for a year.”

Austin had no money and slept on a friend’s couch, but he was terminally infected with the theater bug. When L.A.’s Committee dissolved, he went to the San Francisco company for two years, then returned to join the Comedy Store Players (doing stand-up for a while), where he met Archie Hahn and Valerie Curtin. In 1972 he formed a company that worked out of the Cellar Theater on Vermont Avenue.

” `The Working Class’ was one of the names we were considering, but it sounded too political,” Austin says. “I got the idea for the Groundlings after I read Hamlet’s instructions to the Players. The Groundlings were poor people who sat on the ground and ate box lunches. That was us.”

The kind of theater Austin favored was in the commedia style, “broad, wacky, zany, with costumes and music. The material was in a continuous state of development. We never had to sit around and say, `Let’s do a show.’ We already had one. It came out of the workshop, organically from the work itself. We created simultaneous improvs with a story line. We went all out. You never knew what was going to happen next.”

The company began to grow and voted to incorporate as a nonprofit organization in 1974, “the biggest mistake I ever made in my life,” Austin recalls. “My brother offered the money to keep it private, but I didn’t take him up on it. I became an employee of my own company. It’s a terrible idea to let actors make all the decisions, because actors work in a competitive environment. A workshop should be a safe place to experiment in.”

Tracy Newman saw a harbinger of the future when, after the company moved to a grim industrial space in Santa Monica and Austin found a better room at the Oxford Theater, one of the actors resisted the change of venue because he’d chipped in $2 for a carpet at their present site.

But move they did. In 1974, the Oxford Theater was surrounded by a red-light district, and a steady stream of johns showed up looking for dates. One night two hookers walked in, and when they found out the Groundling was a theater, they joined the company. They did not have hearts of gold. Brass was more like it. “They were very antagonistic and argued with everybody,” Austin says. “After two weeks, they left.”

T he company roster had swelled to 90 with an annual operating budget of $24,000, but the Oxford venue was not, at first, idyllic. One night the entire company performed for one customer. And no one could figure out why the theater reeked of vomit until Laraine Newman discovered that her ritual half-eaten meal of fettuccine Alfredo, left out in the ladies room, went quickly to rot.

But word got out. Lily Tomlin became a fan and one night brought in producer Lorne Michaels, who hired a number of Groundlings for a Tomlin TV special and then took Laraine Newman to New York and “Saturday Night Live.” Paul Reubens developed Pee-wee Herman out of a scene class.

“The character was called Pee-wee Hymen then, and he was unappealing and hostile,” Austin says. “He’d throw Tootsie Rolls at the audience-hard! I got him to soften the character and gave him the suit I wore to auditions. Of course it didn’t fit, but it became so much a part of the Pee-wee look that he went out and had a dozen more made just like it.”

When Ralph Waite took over the Oxford site for his Los Angeles Actors’ Theatre, the Groundlings looked for a home in earnest and found it on Melrose, in a building that had been a Carolina Pines restaurant, a furniture store and a massage parlor. The late theater producer Margie Newman (Laraine and Tracy’s mother) lent $18,000 to take over the building, and the staff, meaning mostly Austin and Archie Hahn, threw out the soiled mattresses that littered the interior and began to rebuild.

It took four contentious years for the building to come up to code, during which time the Groundlings played several venues, including the Improv and the White House on Pico Boulevard, where Kentucky Fried Theatre had made its local start before the Zucker brothers went on to make “Airplane!” There are some who believe that the company lost a bit of soul when it finally took occupancy on Melrose. Others say that that’s where its identity became finally rooted. One thing was clear: After years of 13-hour days given to directing, teaching and running workshops, Austin was finished.

“As we became more successful, people began thinking of the place as a showcase to launch careers,” he says. “I wanted the priority to be the work. Divisions began to form. The company has always had this suicidal streak, and there were a lot of negative people around. I was alcoholic at the time. I let people take the theater away from me. If I knew then what I know now, I’d have done things differently. I blew it.”

Austin left the theater in 1979. Archie Hahn, who had done more than anyone to physically revamp the theater, left in a huff when he realized that all his effort didn’t alter the one-person, one-vote rule. “I think he’s still in a rage,” says Tracy Newman-though, reportedly, Hahn’s frequent absences are one of the reasons it took so long to finish construction.

Tom Maxwell, who soon took over after insisting on a company vote, ran a tight ship through the ‘80s.

“I don’t want to comment on what Gary was doing, or why things fell out the way they did,” Maxwell says. “Personally, he’d always given me a lot of responsibility and opportunity. I think he was frustrated with the committee system. Directors like to be in charge.” Maxwell was not uncomfortable with the system, at least at first, and turned out to be a diligent organization man (“He was very product-oriented,” Bill Steinkellner says). Maxwell left in 1989 and with Don Woodard is now writer-producer on TV’s “Dream On.”

“It became more businesslike when Tom took over,” Tracy Newman says. “A lot of people disliked him, but he opened the door every morning. He took on a thankless job, running the company, a really horrible job. But to survive, somebody has to take charge. I think the theater changed drastically after he left. It’s much more cutthroat now. My main concern is that a lot of good people don’t get voted into the company.

“But,” she adds, “it’s still a great place to develop talent.”

Julia Sweeney, who joined the company in 1985, agrees.

“I came down from Spokane, Washington, and went to work as an accountant at Columbia. I’d been thinking of becoming an actress without telling anyone. Where I grew up, actors were looked on as strange people; the chances of making a normal living in show business are slim.

“I heard of the Groundlings and joined-as financial manager. I took classes from Phil Hartman. If it hadn’t been for that school structure, where you move through levels, I would never have had the confidence to keep going. It took me two years to get into the main company. It’s still the place I go for renewal and discovery.”

If the Groundlings’ future is still undetermined, Allison Kingsley, who recently hired on as company manager, believes that a greater emphasis on marketing and publicity will see the group through the ‘90s.

“I think the Groundlings have moved beyond the kind of disagreements that hurt them in the past,” she says. “They’re more aware of the business side of things. I think they’re ready for a move into TV.” She says the group is in negotiation with Fox, through an intermediary, for a TV special.

Says Deanna Oliver: “I think the ‘90s company works in a more realistic mode. They’re more aware of the world outside L.A.. And the writing’s never been better.”

Anniversary week for the Groundlings will consist of a ‘70s night on Monday, an ‘80s night on Tuesday, the ‘90s on Wednesday and an alumni performance night on Thursday.

“I’m ready to vomit with fear,” Tracy Newman says.

What the veterans will remember most, more than good times and bum times, is the Groundlings’ unchanging sense of family. You move on, but you never leave; even the prodigals have their role in absentia.

“I’ll be directing ‘70s night,” Austin says. “None of the negative people are back.”

He sounded happy.

Twenty Years of Groundlings

The Groundlings celebrate 20 years of outstanding improvisational comedy with a special five-night festival.

On Monday the troupe will present “Best of the Seventies,” featuring comedy material and actors from that era. This will be followed by “Best of the Eighties” on Tuesday and “Best of the Nineties” on Wednesday. The week will be capped off by a celebrity alumni show called “Cookin’ With Gas” on Thursday and the premiere of the Groundlings’ latest performance, “Groundlings Good & Twenty,” on Friday.*

Groundling Theatre, 7307 Melrose Ave., Hollywood, (213) 934-9700. All performances, 8 p.m. Tickets: $35.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >> »

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.