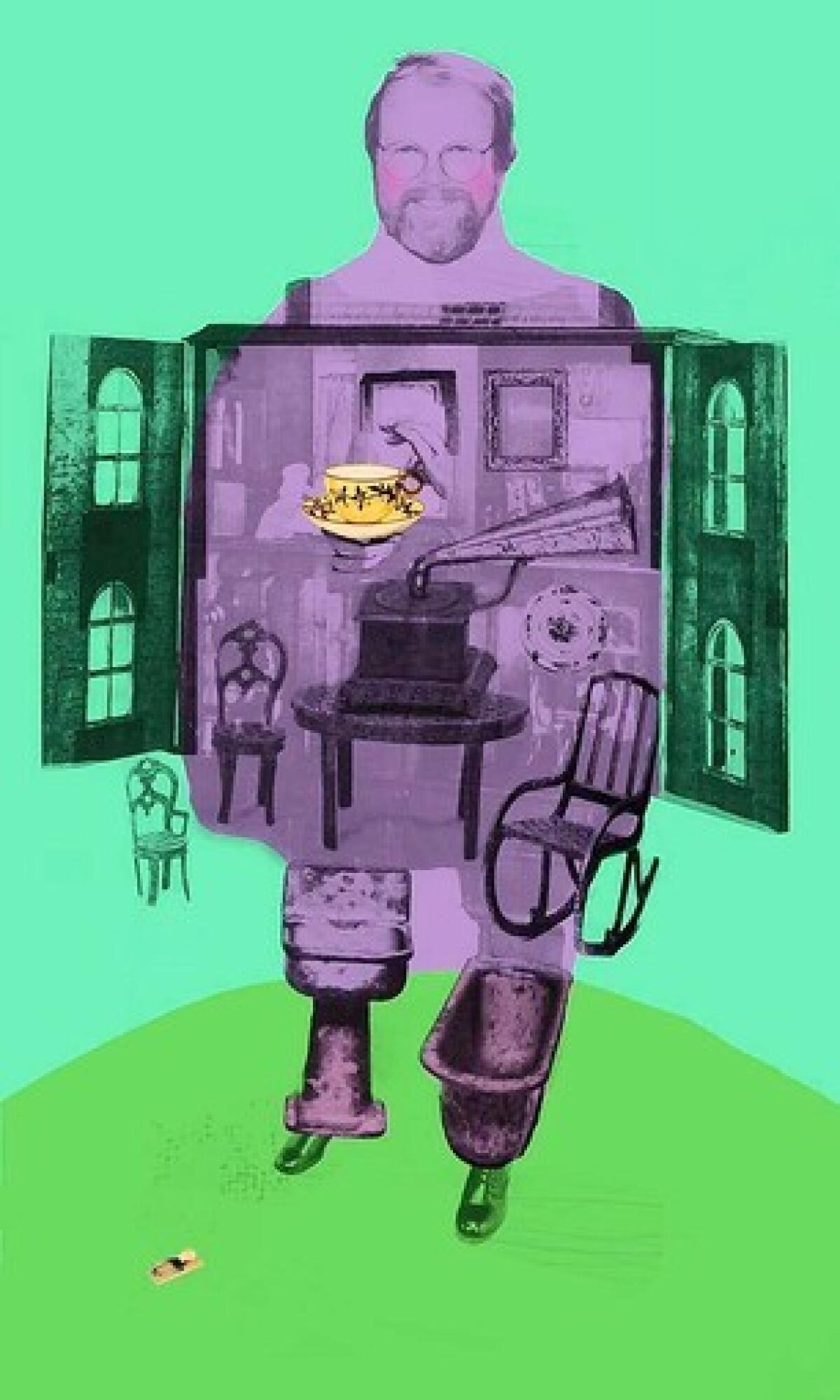

Book review: ‘At Home: A Short History of Private Life’ by Bill Bryson

- Share via

At Home

A Short History of Private Life

Bill Bryson

Doubleday: 500 pp., $28.95

“At Home: A Short History of Private Life” begins on the roof of the Victorian rectory that Bill Bryson and his family occupy in flattest Eastern England. Surveying the surrounding countryside, the American-born author invokes a local archaeologist who once explained to him that the region’s stone churches aren’t sinking. No, they are slightly below ground because the sheer numbers of bodies buried around them over the centuries have caused the earth to rise.

Having imparted this grisly delicacy, Bryson retreats from his roof but not his house. The author best known in the U.S. for his travel writing uses home to anchor his new book; every room in it is a departure point to discuss how those generations of bodies once lived, how their homes functioned and, surprisingly only recently, began to provide a certain level of comfort.

Most of the chapters bear room names: “The Hall,” “The Kitchen,” “The Scullery and Larder,” and so on until the floor plan is conquered, but it would be misleading to imply that this conceit confers order. This book is less residential walkabout than a curio shop crammed to the rafters with things that Bryson finds interesting. What from a lesser writer would be a trivia dump is here a treasure trove. He is an enchanting raconteur — if sometimes excitable.

It takes mere noting the edifice’s year of construction to prompt a tract on Victorian ingenuity and advances in glassmaking. That his house was originally a rectory further compels Bryson to explain the often secular achievements of Britain’s parsons and vicars, along with their sumptuous diets, such as this meal captured in Parson James Woodforde’s 18th century diary: “Dover sole in lobster sauce, spring chicken, ox tongue, roast beef, soup, fillet of veal with morrells and truffles, pigeon pie, sweetbreads, green goose and peas, apricot jam, cheesecakes, stewed mushrooms, and trifle.”

The hallway is used to take us back to the configuration of the earliest human settlements. The kitchen brings to mind tales of food adulteration that made their way into literature (“I’ll grind his bones to make my bread” from “Jack and the Beanstalk”) but probably weren’t true; it also lays the table for an explanation of food preservation and offers the perfect platform for a fresh look at Isabella Beeton, a British forebear of Martha Stewart who recommended cooking pasta for an hour and a half. The scullery chapter explains everything you need to know about the odious British class system and how American society came to differ so profoundly from that of Britain.

An exception to his strict use of rooms comes in “The Fuse Box,” in which Bryson lets drop that one of Thomas Edison’s associates electrocuted himself and that Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt went to a ball dressed as an electric light. Playful yes, but Bryson is also a deft historian, teaching us how entire cities were routinely annihilated by fire until electricity was marshaled.

Though the structural conceit of the book supposedly keeps Bryson at home, the text strays from his adopted country of England, to Scotland, to Ireland, eventually wandering companionably in and out of Monticello and the New York and Florida palaces of robber barons. Construction of the Erie Canal for some reason needs explaining and gets it in the chapter devoted to the cellar. The Eiffel Tower is admired and the Venetian architect Palladio is sketched to explain neoclassical construction. Yet in attitude, outlook and focus, this book is English.

That can be disarming for readers most familiar with Bryson as the Iowa-born author of “A Walk in the Woods.” Since when did the guy who wrote that funny book about trekking the Appalachian Trail become so plummy that the page count of “At Home” might drop were he denied “quite” and “rather”? Since the 1970s, it seems, when he settled there after some college.

A lifetime spent more there than here has Anglicized Bryson to a degree that he irrepressibly splutters queenly modifiers. Yet Bryson’s Englishness feels innate, genuine, less as if he’s left home and more as if he’s found it. Until Bryson produced this book, who but an Englishman would have opened the topic of the home study with the history of the mousetrap?

An American might seek out an MIT expert on household accidents for the stairs chapter, which Bryson does, but with “At Home” he joins the quintessentially British ranks of historians such as Elizabeth David, Lucinda Lambton and Reay Tannahill, all mordant, all brilliant, and all of whom viewed the history of the world through a domestic lens.

The book closes with Bryson back on his roof in Norfolk, wondering, given all the timber, brick, stone, concrete, iron, steel, porcelain and fuel that it’s taken for wealthy nations to achieve such comfortable homes, if there will be enough natural resources to do the same for poor ones? But he does not dwell on that. The thousands of small things he’s imparted add up to one big lesson: much tragedy and ingenuity will have passed before that question is answered, by which time Bryson, like us, will be causing the ground to rise.

Green writes the Dry Garden column for The Times. She is completing a book on water in the Great Basin.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.