How family revelations enriched A.M. Homes’ new novel about a MAGA-type cabal

On the Shelf

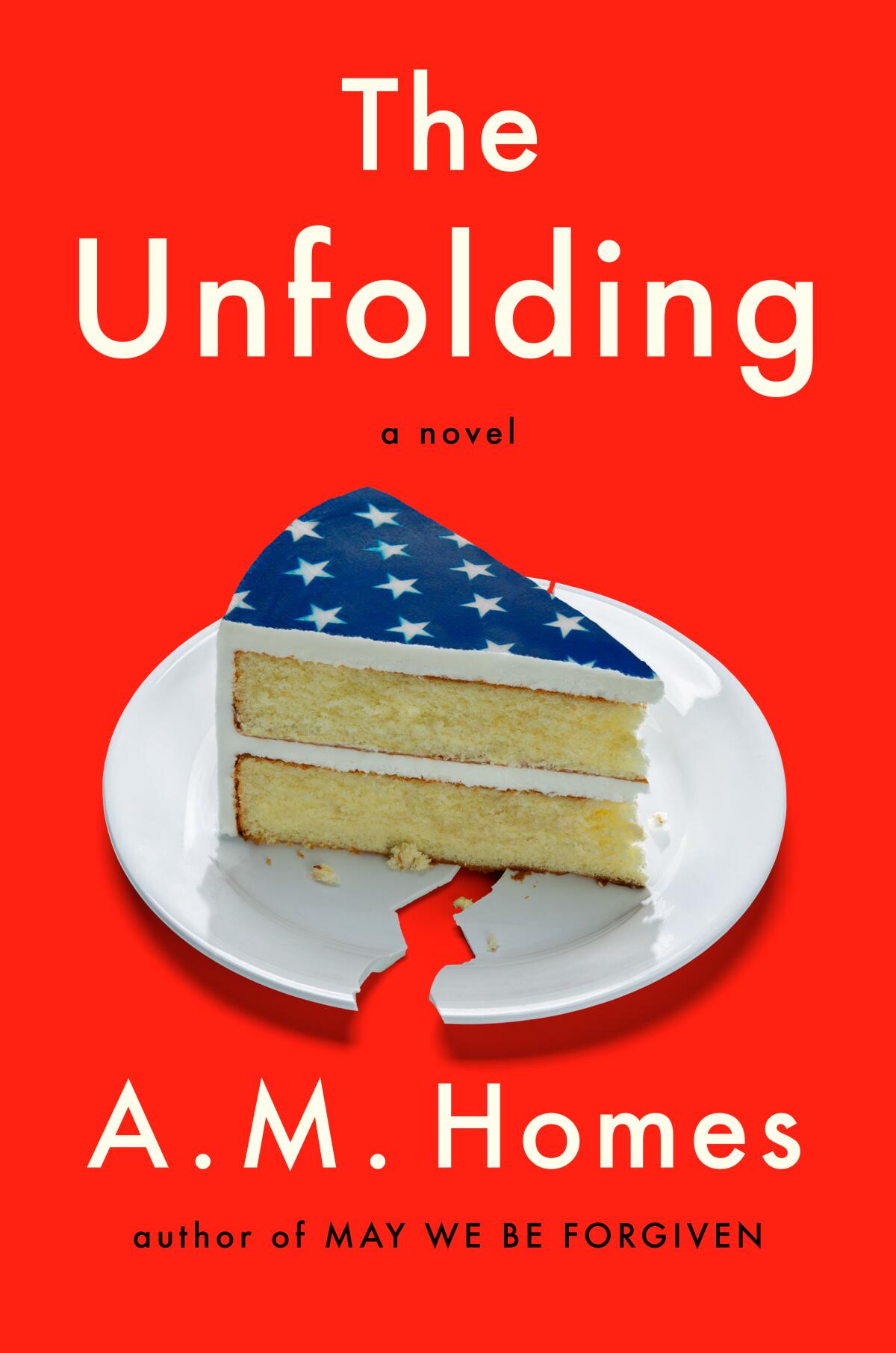

The Unfolding

By A.M. Homes

Viking: 416 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A.M. Homes is well acquainted with controversy. Her first novel, “Jack,” written when she was 19, has been among the American Library Association’s most banned and challenged books since its publication in 1989. Her fourth novel, “Music for Torching,” poked a nerve at an explosive moment. It dealt with a school shooting, and its publication date — April 20, 1999 — coincided with the massacre at Columbine.

Her newest novel, “The Unfolding,” has a similar claim to eerie prescience. Homes began writing it more than a decade ago, around the time of President Obama’s defeat of Sen. John McCain. In the book, a character identified only as “the Big Guy” organizes a group of wealthy Republicans to form the “Forever Men,” a secret cabal pledged to use any means necessary to keep themselves and their species in power. They assume the women in their lives will fall in right behind them. But the Big Guy’s wife and daughter are not that pliable. They make discoveries that propel them on wacky journeys of their own.

I recently sat down to discuss “The Unfolding,” which is out this week. The novel pairs slapstick political satire with tender observations about the relationship between parents and children. Aspects of the story recall Homes’ own adoption memoir, “The Mistress’s Daughter,” which charts her birth mother’s unexpected appearance in her life and the discovery of her biological father. This is her first novel since “May We Be Forgiven,” which won the 2013 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Homes and I have been professional acquaintances for years. In the early 1990s, mutual friends insisted that we meet. At the time, I was writing a cultural history of the Barbie doll and Homes had recently published “A Real Doll,” an unsettling short story that begins, “I’m dating my sister’s Barbie.” Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Fall arts and entertainment picks from music, books, TV, arts and movies.

“The Unfolding” felt authentic because its fictive characters interact with real people. For instance, Malcolm Moos, who wrote President Eisenhower’s 1961 speech warning against the “military-industrial complex,” is a real person. And George Washington too. What took you by surprise when you were doing the research?

I have been fascinated by that sense of confidence that comes from not only knowing one’s history but having a legacy that is one of historical importance. As I was finishing the book, this strange piece of information came to me: My ancestors had owned the land that is now Capitol Hill — like all the land.

Ancestors of your biological father?

Yes, Dr. Thomas Gerrard. I also learned that two of my ancestors — they were sisters — were sequentially married to George Washington’s great-grandfather. There’s something about literally writing one’s way toward a kind of history that you know on some level, without quite knowing what you’re doing.

Are you saying you knew this on a genetic level?

I am. My biological father had said things — and his own behavior was a bit “Big Guy”-ish in that sense of a large-scale confidence and sense of ownership or privilege of place. And I didn’t fully understand this. But when I discovered this piece of information it made much more sense.

Who was your biological father?

A banker in Washington, D.C. In the book, the thread of the Big Guy and his daughter Meghan is an echo of my life but also completely different. Because obviously I didn’t grow up with my father. And we had none of those conversations and never spent more than 36 minutes together.

Your fiction has tended to be ahead of the curve — to depict cultural upheavals before they happen. Is it prescience or is it reading the culture?

It’s not in any way the first time I’ve written my way toward something. When I was writing “Jack,” my teachers would say, “This will be very controversial.” And I remember wondering: Why? Was it because at the time there were no books about kids whose parents were gay? Was this prescience? I like to think as a writer that it’s reading the culture.

Longtime D.C. reporter Dana Milbank talks about “The Destructionists: The Twenty-Five-Year Crack-Up of the Republican Party,” and what needs to change

I love the way you evoke the values of an entire class with three vanishing terms: “noblesse oblige, haberdashery, and supper.”

I was thinking about a generation that to me is quickly fading. When I look at what happened with Trump, you see so much failure to obey the rules. Many of these rules were unwritten because nobody thought we ever had to write them. Because the expectation was that people would behave accordingly — and that they all had the same desire to preserve democracy. But then one of my editors in England said: “Well, I’m confused because they keep talking about their desire to ‘preserve democracy’ but they don’t seem to want to.”

And I’m like, well, now democracy means different things to different people. Your “democracy” and my “democracy” are not necessarily the same things.

Where do the Forever Men — and their plans for disruption — fit in? The book ends before Trump emerges.

I’ve always been very interested in America post-World War II, the investment in the American dream and the loss of understanding of the dream. This dovetails with the rise of big money and dark money in politics. I imagine these men looking at Trump and asking, “Did we do that?” In other words, would this be traceable to them?

What did you hope to achieve with this novel?

It’s important to me that this book is a weave of the ideas that one thinks of as the Great American Novel — i.e., a novel written by somebody named Jonathan (that’s what Jonathans do) — and the Intimate Domestic, which is also the Female Novel. This was a chance to weave those together and to capture the large sociopolitical ideas and experiences with that of the family. It also illustrates the differences between our public and private selves. The way the Big Guy is one person with his family and another version of himself when he’s with the Forever Men.

Despite its humor, the book paints a grim picture of America. Is there anything to be optimistic about?

In looking at the January 6 hearings, I look at all the women — the young women — who stepped up and came forward with information. Who put themselves in difficult positions. They were in those rooms and witness to things and men discounted their presence.

Meghan is very specifically her own person. She’s coming into her own and realizing that she may see the world differently than how it was described to her by her family. That process of individuation and separation is universal. I liked watching her discover her own sense of agency. If you don’t step into yourself in some ways, no one’s going to push you there. The Big Guy may think she’s going to fall in with his ideas. But that’s the Big Guy being naive about his point of view.

The Mistress’s Daughter A Memoir A.M. Homes Viking: 238 pp., $24.95

Lord, author of “The Accidental Feminist,” is an associate professor at USC.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.