Review: ‘The Exorcist’ falls short of a devilishly good time

Two questions immediately presented themselves when it was announced that “The Exorcist” was going to be done onstage: How? And why?

At the show’s premiere Wednesday at the Geffen Playhouse, the creators seemed to be searching for answers to these challenges. God doesn’t appear to be on their side.

The how, at least on a visual level, turns out to be far more interesting than the why, which leads to all kinds of armchair moralizing and faux philosophizing. But fans of William Friedkin’s 1973 film — a work that has caused more bad dreams than any other movie in Hollywood history, if my childhood is any guide — shouldn’t expect any ostentatious spinning of heads. (No projectile vomiting, either, thank heavens.)

PHOTOS: ‘The Exorcist’ on stage

The John Pielmeier play, which returns to William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel as its source rather than the film, takes itself rather seriously. Lest there be theatergoers out for escapist thrills, the first words we hear are from Father Merrin (Richard Chamberlain): “For anyone who doubts the existence of the devil as I once did, I have three words. Auschwitz. Cambodia. Somalia.”

All at once the audience sat up a little straighter, as though out of fear that Father Merrin might start roaming the aisles and rapping knuckles.

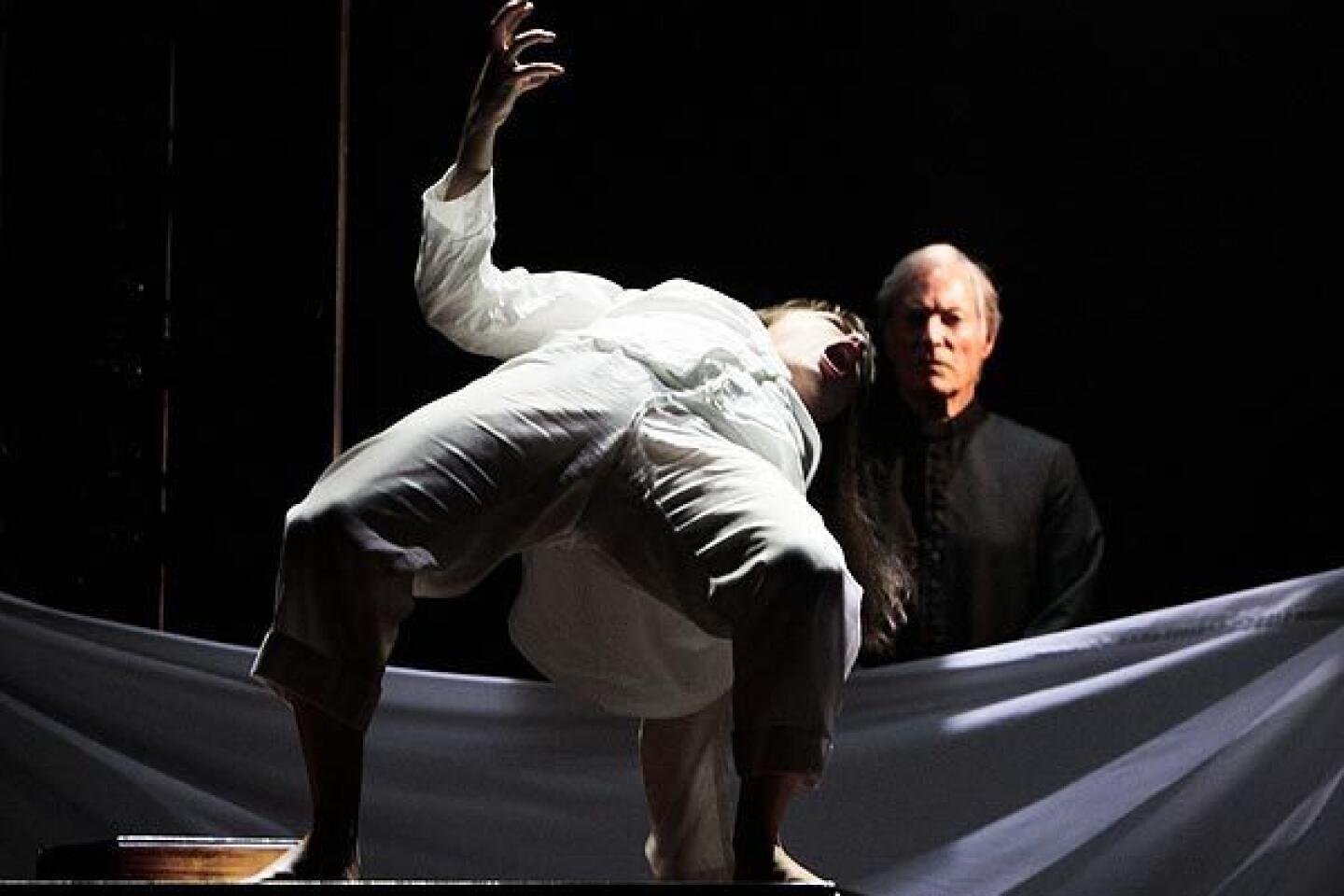

The frightening elegance of the stagecraft, however, seizes that part of our imagination responsible for night terror. The prospect of a date with the boogeyman draws us in. Few want to go all the way, but most wouldn’t mind getting to second base, which director John Doyle makes possible in a production that treats the drama as a quasi religious ritual.

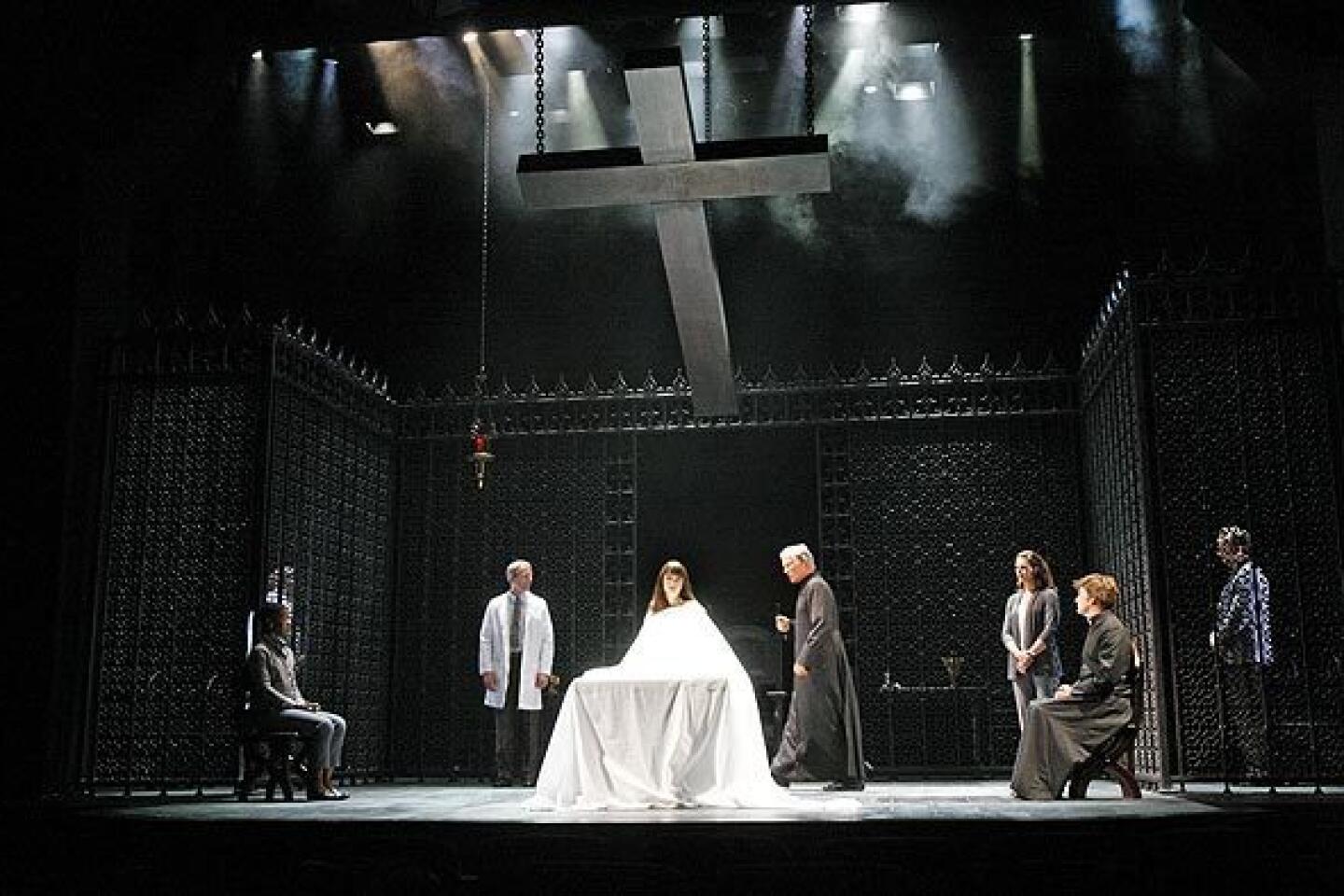

Scott Pask’s strikingly original scenic design transforms the stage into an altar, where in the opening moments of the play, Regan MacNeil, the demonically possessed little girl (vividly played by UCLA grad Emily Yetter), desecrates a Communion wafer.

I’ll admit I found this a bit shocking, which is not easy to accomplish these days in the theater, but then my body was momentarily taken over by the ghost of my Italian American grandmother, who let out an outraged gasp.

Forbidding church gates partly conceal an area at the back of the stage where cast members whisper, intone and shout out, creating a diabolical soundscape by Dan Moses Schreier that works in perfect tandem with John Tavener’s music. The brilliance of this effect leads me to believe that Doyle, who won a Tony for his chillingly inventive staging of “Sweeney Todd,” was tempted into this rather outlandish project by his ears rather than his common sense.

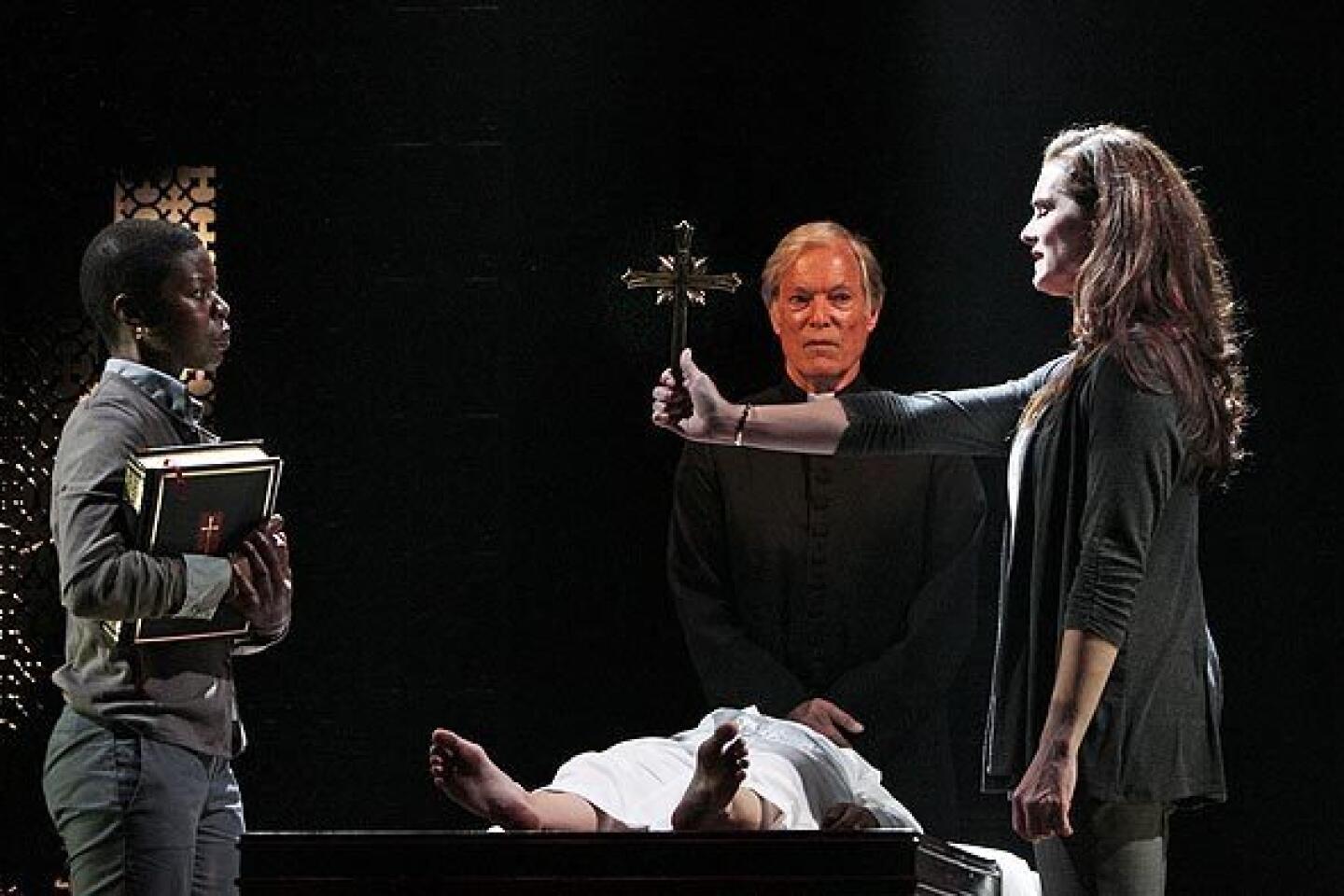

The physical production is just so much more persuasive than the dramatic encounters contained within it. The casting of Brooke Shields, lovely as always to look at, doesn’t enhance the work’s credibility, although I think she would be terrific in an alternative camp version directed by John Waters. Playing actress Chris MacNeil, the bewildered mother of the havoc-raising child, Shields lends her lines a B-movie obviousness that cries out for an exorcism of a different kind, one requiring the mystical skills of an acting coach rather than a priest.

The performances, save that of Yetter’s, are all a bit off. But then it’s hard to blame Harry Groener for appearing over-the-top as Burke Dennings, the drunken movie director who’s making the film in Washington, D.C., that Chris is starring in. With an oversized Ash Wednesday cross on his forehead, he careens around the stage guzzling booze in a chalice.

Realism clearly isn’t what Doyle is aiming for, although the play is constantly churning up modern concerns. There’s talk of African genocides, largely stemming from the presence of Carla (Roslyn Ruff), Chris’ domestic helper who was a first-hand witness to the hell in Rwanda. And there are suggestions of loose conduct, if not sexual inappropriateness, involving the two priests, Father Joe (Manoel Felciano) and Father Damien Karras (David Wilson Barnes), a Jesuit psychiatrist whose crisis in faith has been exacerbated by the death of his mother.

It wouldn’t be fair to hold the actors responsible for the stilted dialogue supplied by Pielmeier, who doesn’t trust the dramatic action to embody his play’s meaning. Everything is a tad over-explained. If one rationale seems a little dubious, he’ll drop in a second and perhaps even a third. Consequently, the colloquies between characters grow tedious, stuffed as they are with artificial import.

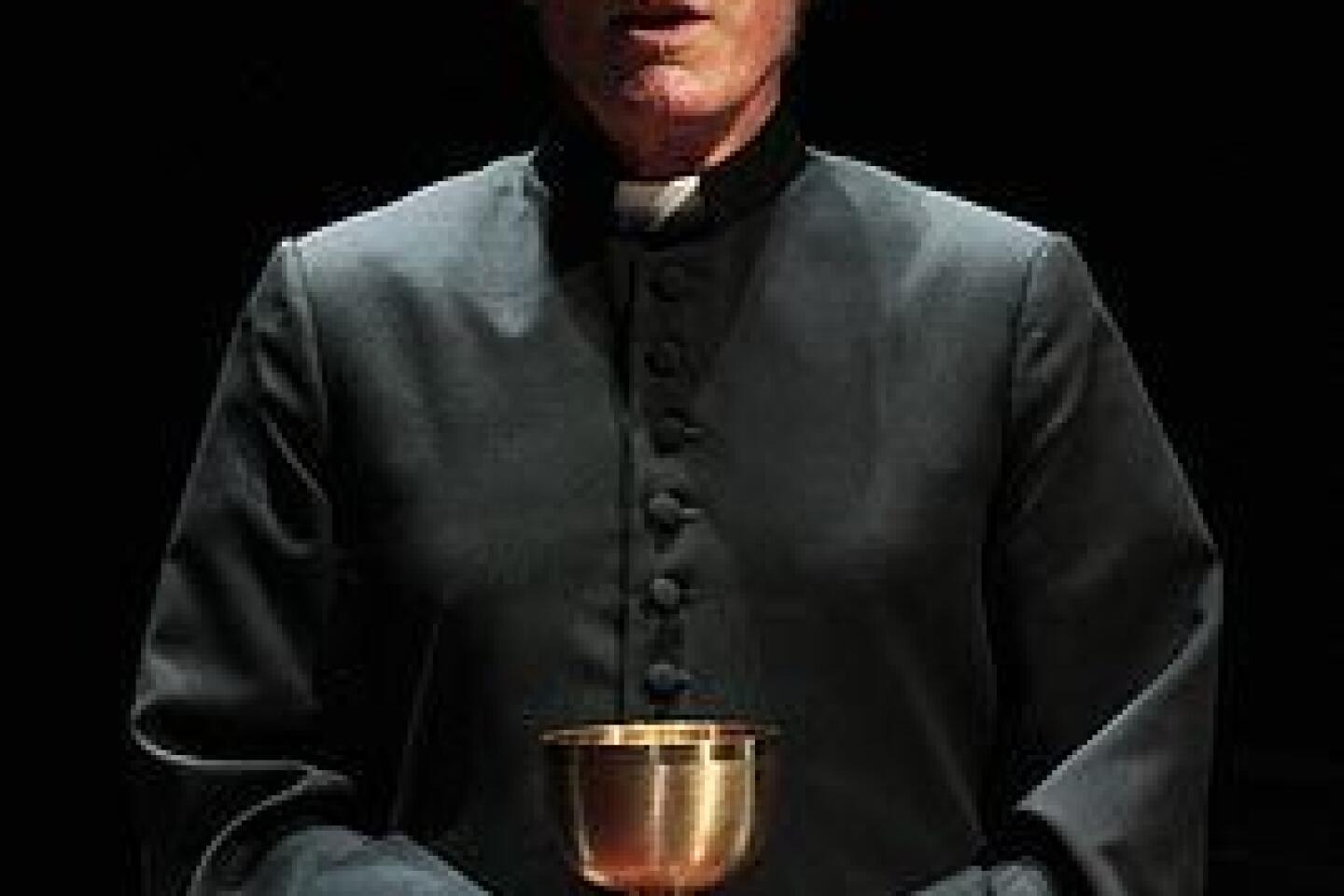

Chamberlain is saddled with the worst of it. His character is the exorcist, but he also serves as the play’s pontificator, routinely interrupting the story to deliver a mini homily on its meaning. Fortunately, the veteran actor is a smooth operator, and for the most part his velvety voice undercuts the strained theological navel-gazing that Pielmeier, author of “Agnes of God,” can’t get enough of.

But there’s little that can be done when, after Regan has just chewed off a piece of one of her doctor’s ears, Chamberlain is compelled to deliver the following footnote: “This is a struggle between good and evil — for heaven’s sakes, even if you don’t believe in the devil you can embrace a metaphor, can’t you?”

Thanks kindly, but I prefer to discover my metaphors for myself.

Why can’t the tale, even if it occasionally speaks in tongues, communicate without this disruptive annotation? The plight of an innocent daughter corrupted by something beyond her control exerts a disturbing hold, and Shields, to give credit where credit is due, does convey the guilt and anguish of a mother’s helplessness.

Yetter, although an adult, has a childlike quality that is at once tender and otherworldly. Gymnastically impressive, she doesn’t need many special effects, though Teller (of Penn & Teller) has been brought in as a creative consultant and there’s a bit of levitating that should offer solace to disappointed sensation-seekers.

But “The Exorcist,” even in this modern update, seems like old hat. Maybe there’s just no room anymore on the list of things to worry about for demonic possession. If Satan shows up, he’ll have to get in the back of a very long line.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.