The problem with David Mamet

Critic’s Notebook: The dramatist who used to regularly scorch the stage with complex stories has let his anti-P.C. rage blunt his work.

What in the world has happened to David Mamet? The Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “Glengarry Glen Ross,” a modern classic that can survive even the ham acting of Al Pacino at his Broadway goofiest, has become a wide-ranging controversialist, ever ready to tap dance on eggshells with military boots.

Music producer Phil Spector was convicted of murdering actress Lana Clarkson at his Alhambra mansion. Mamet retries the case on HBO in a counterfactual film he wrote and directed that perversely makes Spector the victim of his — cry me a river — outsize personality and fame.

FULL COVERAGE: 2013 Spring arts preview

Mamet’s forays into opinion journalism (such as his cynical column last fall in the Jewish Journal reminding those misguided “Jews planning to vote for Obama” of the secret nature of the ballot) are more plausible as the work of a Mamet character than the dramatist who, to rephrase the Auden-inspired compliment once paid to Harold Pinter, cleaned the gutters of American English on stage with his ferocious patter and highly individualized profanity.

Mamet’s shift to the right has allowed his defenders to dismiss criticism of his views as liberal bias. I don’t subscribe to Mamet’s ideologies, but the problem for me has less to do with the nature of his reactionary positions than with the way he has allowed the polemicist to overshadow the dramatic poet.

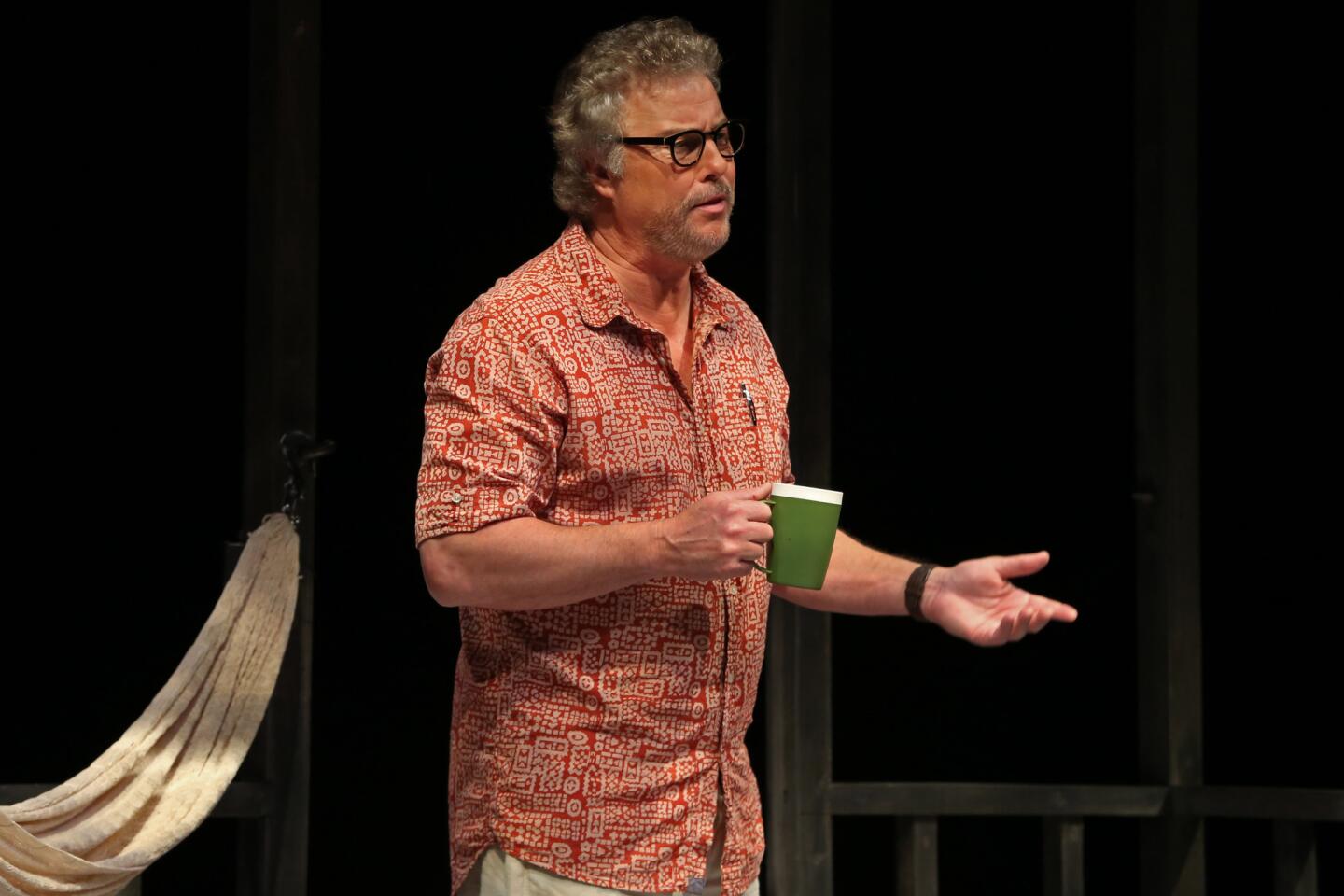

This is one reason I’m eager to see “American Buffalo” when it opens April 10 at the Geffen Playhouse under the direction of Randall Arney. I want to remember the scrappy Chicago tough guy who revolutionized the way characters speak on stage and forget the swaggering Hollywood transplant forever venting his spleen like a bathrobe-wearing crank in a Saul Bellow novel firing off letters to the editor at the vaguest suggestion of a partisan slight.

I’d also like to develop a case of amnesia that would be limited to Mamet’s last three new plays on Broadway: the soggy political farce “November” (later ineptly staged at the Mark Taper Forum), the red-herring-crammed “Race” and the quarter-baked “The Anarchist.” The latter, feloniously wasting the talents of Patti LuPone and Debra Winger, was of such inferior quality that Broadway producers, not by nature soul-searching types, were forced to publicly account for their lack of business (never mind theatrical) acumen.

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

I don’t believe it’s fair to ask writers to perpetually live up to the standard of their best work. A fellow journalist asked me recently whether I thought Tom Stoppard’s star had dimmed as a playwright. I was surprised by the question.

At 75, Stoppard hardly has to keep turning out work of the first rank to maintain his standing. If he were never to write another play, we would remain in his debt for “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead,” “The Real Thing,” “Arcadia” and “Rock ‘n’ Roll.” That he keeps turning out screenplays (for the underrated “Anna Karenina”) and television scripts (for the artful “Parade’s End”) only enhances the luster of his reputation for supremely articulate drama.

Mamet’s place in the theater history books is just as assured, though the addendum he’s writing is a doozy. One can’t fault him for his energy or rate of production. He’s more prolific at 65 than most playwrights are at 30. No, his problem dates back more than two decades to “Oleanna,” the play in which he took on the bugaboo of political correctness and got mired in a battle within his own mind that seems destined to become a second Thirty Years’ War.

PHOTOS: Best in theater for 2012

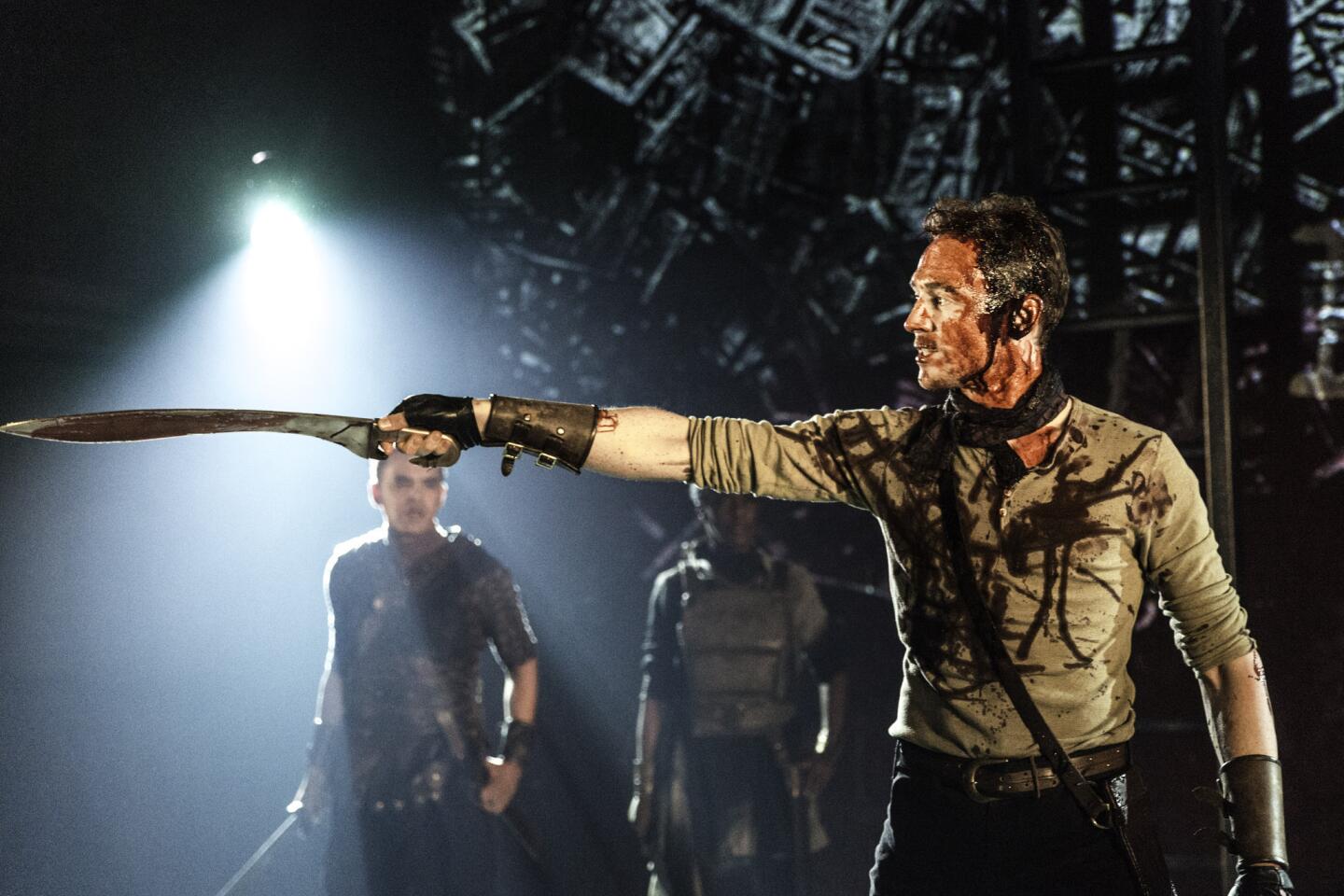

Written in the charged wake of the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas controversy, “Oleanna” dramatizes the conflict between a male college professor and a female student whose seemingly ungrounded accusations have disastrous consequences on his academic career. The play possesses an undeniable Mametian vigor in its demonstration of the way insecure power games play out in language. But the deck is so shamelessly stacked that it’s never a fair fight.

The student’s wrath, stoked by an unseen “group” of jargon-spewing feminist rabble-rousers, distorts everything we have witnessed between the two characters. What’s more, Mamet keeps reminding us of all the professor has to lose by her trumped-up allegations. During the play’s off-Broadway run in 1992, men in the audience were reportedly erupting in misogynistic hurrahs when the professor finally unleashed his anger — a reaction more in keeping with the black-and-white morality of melodrama than with the ethical subtleties of superior drama.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by The Times

“Oleanna” polarized audiences on the issues it manipulatively addressed. But the huge uproar made the criticism seem as if it were politically rather than aesthetically motivated. The profound shortcomings in character construction, the numbing artificiality of a good deal of the dialogue and the pre-decided nature of the dramatic argument are faults of craft that were overshadowed by the vehement reactions to the content.

When considering the plays Mamet has written since “Oleanna,” I’m surprised to find only one that I’d truly be excited to see revived: “The Cryptogram,” first produced in London in 1994, two years after “Oleanna” had its premiere in Cambridge, Mass. But then this elliptical, backward-looking drama about the menace and mystery of childhood has no outside agenda to undermine its fictional authenticity. More important, it has what so many of his ax-grinding recent plays conspicuously lack — a genuine sense of discovery.

Mamet’s drama is at its best when the characters seem to be improvising their fates alongside their author. But this requires unusual artistic suppleness, and the sad truth is that there’s been a hardening in his work not just of ideology but of imagination. As Mamet has become an institution, a brand, a Broadway staple and a Hollywood hotshot, his plays have grown brittle, self-conscious and divorced from lived experience.

Artists who are path-breakers are unusually susceptible to self-caricature. Rewarded for their originality, they run the risk of parodying what made them great. Alert to the danger, Mamet has allowed himself to frolic from time to time in pastiche forms.

“Boston Marriage” had him trying his hand at drawing room comedy; “November” found him recycling farcical shtick from the trunk of George S. Kaufman. Mamet has even adapted Harley Granville Barker’s “The Voysey Inheritance” for the stage and Terence Rattigan’s “The Winslow Boy” for the screen — two English playwrights whose decorous manners wouldn’t seem an obvious draw for an American dramatist who strings four-letter epithets with all the insouciance of a rap star.

His wide-ranging film work (he wrote and directed the oddball comedy “State and Main” and co-wrote the Oscar-nominated screenplay “Wag the Dog,” among other credits) has no doubt encouraged this adventurous streak. But in the theater these explorations inevitably seem like diversions from the main act, as though the author were taking a holiday from his combustible sensibility. Mamet has a patented flair for comedy. Yet neither “Romance,” with its kangaroo courtroom antics, nor “Keep Your Pantheon,” with its ancient Roman horseplay, amounts to much more than a cocktail napkin doodle.

Yet his ire is clearly no longer serving as a reliable muse. (Retrospection might be more fruitful, as “The Cryptogram” and “The Old Neighborhood,” perhaps the second best work in his post-”Oleanna” period, suggest.) In his younger days, Mamet turned con men into feisty symbols of the fiasco of American capitalism. Now an unregenerate capitalist himself, he’s been on the hunt for all those have-nots eager to pick his pocket with their outlandish demands for justice, equality and fairness.

There are no good guys in Mamet’s plays, but it’s possible to tell where his sympathies are through glimpses of what lies behind the mask of his sneakier operators. In “The Anarchist,” which revolves around the parole decision of a convict associated with a radical Weather Underground-like movement, the details that emerge about the prisoner only tautologically confirm the foolishness of second chances for those who don’t deserve them in the first place.

Funny, isn’t it, how a play can conclusively prove the truth of its playwright’s bias? Funny for anyone, that is, not paying an arm and a leg to see LuPone and Winger try to breathe life into lines only a typewriter could pronounce.

Some might argue that Mamet is providing a useful service, challenging articles of liberal faith from inside the elitist stronghold. But his contrarian streak, once the source of his independent vision, has become all too predictable. There’s nothing especially radical in siding with power over those seeking restitution for their lack of it.

Writing at the highest level requires an “incandescent” imagination, one unencumbered by too much anger or bitterness, as Virginia Woolf argues in “A Room of One’s Own” — a book not likely to be among his dog-eared college favorites.

Mamet has been using the bully pulpit granted to him as an artist to broadcast the doctrines of loudmouth talk radio, that boisterous realm in which innuendo substitutes for evidence and fear-mongering replaces analysis. That’s his prerogative as a citizen. But what a shame for progressives and conservatives alike that such a gifted dramatist has allowed his hotheaded dogmas to ruin his art.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.