Black Film Archive revives an ignored history of cinema through streaming

Many questions pushed Maya Cade to create the Black Film Archive website, a new, curated streaming guide of Black cinema spanning 1915 through 1979: What films belong here? How can I present it in a way that doesn’t harm my community? But one forced her to pause before sending it into the world: Do people need this?

The question didn’t come from a place of doubt, but rather a place of careful consideration about how to present the films with context that explains their place in history. In the process of creating a trusted resource for historic Black films, Cade says doing that responsibly is the most important consideration she faces with this project.

What is canon in American film history? Maya Cade’s Black Film Archive sets out add ignored Black titles.

“If my whole intention was to do this with the community in mind ... then there’s the even greater question: Are they ready for this and are they ready for what it could become?”

Examining the notion that Black film, pre-Spike Lee, is a monolith of racial trauma rehashed in the Hollywood-approved canon of films is exactly the reason Cade spent more than a year compiling a list of approximately 250 Black films from streaming platforms like Tubi, Criterion and HBO Max, as well as YouTube and other public domain sites. The Black Film Archive brings the forgotten works of legends like Oscar Micheaux and Zora Neale Hurston to one place, sorted by decade, with links to where they’re streaming and descriptions of the films.

Her project comes at time when mainstream institutions have begun examining Black representation in movies and realizing that important works have been left out of the canon of American film. Consider that the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, which will open to the public in Los Angeles on Sept. 30, is devoting a gallery that gives equal billing to Micheaux’s career alongside the films “Citizen Kane” and “Real Women Have Curves” as well as Bruce Lee, film editor Thelma Schoonmaker and cinematographer Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki.

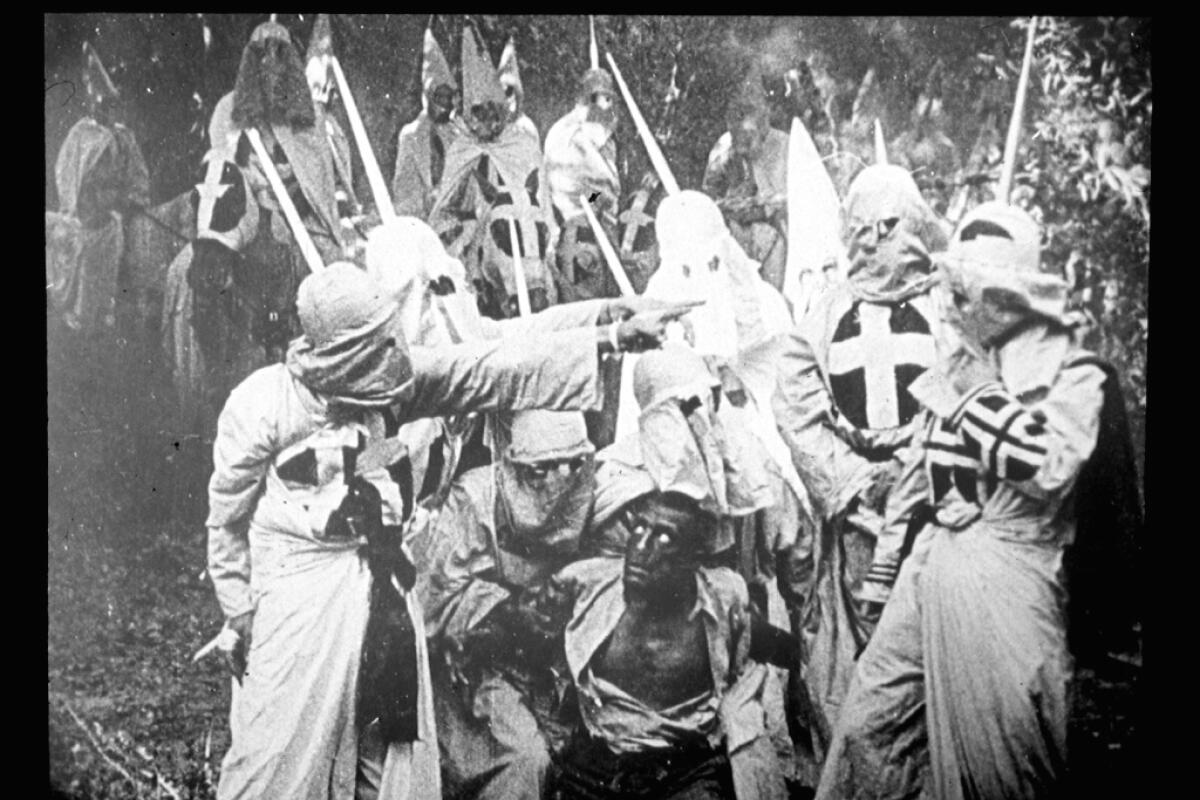

“This moment reminds me,” Cade says of the academy’s acknowledgment of Micheaux’s legacy, “that we’ve never really fully celebrated and embraced this man who’s financed, written, produced and directed films about Black people as Black people were fighting to be seen as humans, and fighting for our humanity to be recognized. It’s a fight that continues a century after his first masterwork, ‘Within Our Gates.’”

Cade was particularly committed to archiving Black films made before the 1980s, which she describes as the “new era of Black cinema” that ushered in a wave of contemporary icons like Lee, John Singleton and Robert Townsend. The Black Film Archive gathers works too long relegated to the tombs of dusty VHS cabinets, films like “The Cry of Jazz,” a 1959 documentary chronicling the history of jazz and its impact on American history, and “Killing Time,” a master class in offbeat suspense about a woman who plans to kill herself but won’t do it until she finds the right outfit to wear.

“Killing Time” “just reminded me that there is a film from the past for everyone,” says Cade, who works as an audience editor for the Criterion Collection and created the archive in her off time. “This film that I’ve never heard of — because it’s rarely streaming and not very accessible — is just incredible.”

Since it debuted in late August, the Black Film Archive has been widely praised by Black cinema fans and movie directors, confirming for Cade that, yes, people do need this platform as much as Cade needed to create it.

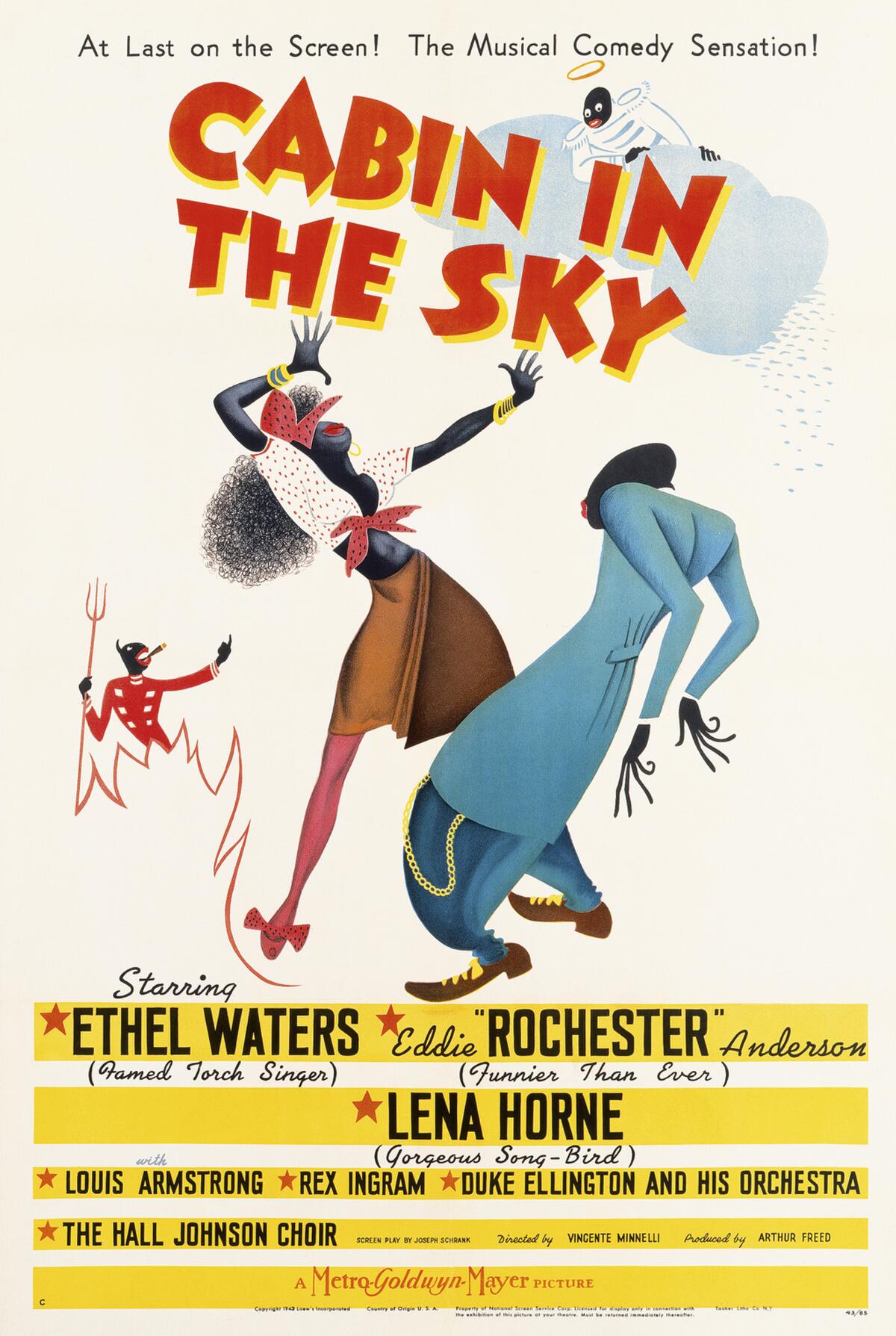

Like many, Cade sought a way to spiritually and emotionally sustain herself during the pandemic and the cultural shock waves created by Black Lives Matter. In June 2020, she began a Twitter thread of links to video streams of classics like “Cabin in the Sky” and “Boarding House Blues.” The tweets went viral, and soon her casual internet searches turned into spreadsheets of all the titles she could research from a dozen or so books on the history of Black film.

At that point she knew she couldn’t stop, so she decided to make her own platform online.

“I realized that I can pour myself into this because there’s a community that already trusts me, people really are engaging me about Black film, that’s all I talk about online,” Cade says. “I was like, ‘OK, you have community trust. That’s a place to start.’”

George Lucas’ art museum acquires the Separate Cinema Archive, which includes 37,000 items of black film history.

Filling a uniquely Black need for historical films means including titles that celebrate Black pride, as well as films that shake it to its core. Paul Robeson’s denunciation of 1935’s “Sanders of the River,” in which he starred, raises questions about the role of racism in film editing — Robeson attempted to ban the film after it was edited into a pro-imperialism story without his knowledge.

Flashing forward 40 years, Cade struggled over whether to include the 1975 film “The Black Gestapo,” undoubtedly one of the weirdest titles in the blaxploitation canon. In this Black Panthers spoof, a militant Black group called “The People’s Army” protects the Black residents of Watts from “The Man.” “As their control in the community increases, so does their leader’s thirst for power,” according to the Black Film Archive’s description.

The film is full of Nazi imagery, with messaging that implies even those who fight fascism can become fascist if they are addicted to power. “But it almost loses itself on the way to its point,” Cade says. At one point the people are in the struggle together, and then at another point the film is saying the People’s Army is no better than the army of white supremacists they’re fighting.

“This is one of the films where I was just like, ‘OK, this is pushing a line, and what does that line mean? What is the value for people here?’” Cade says. “It’s definitely a film that couldn’t be made today.”

Cade also wrestled with her decision not to include the work of Bill Cosby, who had starring roles in half a dozen or so films before 1979, including “Uptown Saturday Night,” “Let’s Do It Again” and “A Piece of the Action.” Cade says she’s received emails from people asking if Cosby’s absence in the archive means she’s decided to ignore his films altogether. She explains that one reason Cosby’s films haven’t been added to the site is because they consist mostly of rentals, which are not accessible yet through streaming. Adding rentals from sites like Amazon is a task she says she’s working to complete.

“It’s not a question of whether or not Cosby will be on the site, it’s a question of how to include him on the site and what will that look like?” Cade says. “If my mission is to talk about Black film of a certain time period, the question is: What is the value and how do I do that in a way that does the minimal amount of harm to people I want to serve in my community?”

Cade hopes to help new generations of film buffs open up to alternative examples of Black culture depicted in past films, whether people agree with the portrayals or not. While it might seem that a black-and-white silent film from the 1920s has little relevance to younger Black audiences, Cade says the archive can improve young people’s relationship to Black film by finding new definitions with the help of a forgotten history.

“People will say things like, ‘Oh, all Black films of the past are traumatic; why would I watch that?’ Or, ‘All Black film’ is this or that. ... It’s such a binary that Blackness exists on,” Cade says. “I think with the archives I’m saying, ‘No, we are expansive and we contain multitudes.’”

The Black Film Archive is at blackfilmarchive.com.

Oscar Micheaux, once chided for his technique, died an unknown in 1951. But his reputation is on the rise.

The name of Oscar Micheaux won’t register with a lot of people when the subject of the earliest days of the movie western comes up.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.