Marshall McKay, Indigenous leader who helped steer Autry Museum, dies of COVID-19 at 68

Marshall McKay, a Northern California Indigenous leader of Pomo-Wintun heritage who helped secure economic independence for the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation near Sacramento, and whose deep support of cultural causes led to his becoming the first Indigenous chairman on the board of the Autry Museum of the American West, has died at 68 after contracting the coronavirus.

Last month, McKay and his wife, Sharon Rogers McKay, tested positive for the coronavirus and were both hospitalized after experiencing severe COVID-19 symptoms. Rogers McKay recovered and was eventually released. Her husband did not. Marshall McKay died Dec. 29 at Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center in Los Angeles. His death was confirmed by a representative for the Autry Museum and his stepson, Alex Aander.

Rick West, president and chief executive at the Autry, said McKay’s death marks a huge loss for the museum but also Native culture at large. McKay was, West said, “one of the five — maybe even three — significant Native leaders in the late 20th century and early 21st century period.”

“We will miss his strength and wisdom,” said a joint statement issued by the members of the Yocha Dehe Tribal Council. “He was a resolute protector of Native American heritage here, within our own homeland, but also throughout California and Indian Country.”

His stepson describes a congenial family man who loved road trips, Nicolas Cage movies and his chihuahuas — at one point he had a brood of 10 — the most beloved of which he named Frida Kahlo.

“I know that he has done so much incredible work in his life and I know only a small fragment of it,” Aander said. “I knew him as a human being. … My biggest memory is road trips. We would drive around the countryside for hours and let the rock ’n’ roll do the talking.”

McKay, who was the first in his tribe to go to college, was involved in tribal governance for a three-decade period starting in the 1980s and helped the Yocha Dehe expand its land holdings in its ancestral territories in what is now Yolo County. He also helped the tribe achieve economic independence through a casino development — the Cache Creek Casino Resort, about an hour’s drive west of Sacramento. Half a dozen years ago, with his involvement, the tribe expanded into agricultural production, which included the development of Séka Hills, a brand of artisanal olive oil.

If economic issues were important to him as a tribal leader, so were cultural ones.

“The economics and the fight for sovereignty — the things I fought for all of my life — I think we’ve got that,” he told the Sacramento Bee in 2006. “Now we need to revitalize our spirituality, our culture — for the young people.”

McKay was a founding member of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, which supported Indigenous artists and culture. In 2007, he was tapped by Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to serve on the Native American Heritage Commission. Shortly thereafter, he joined the boards of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington and the Autry in Los Angeles. At the time, the Autry had recently merged with the Southwest Museum of the American Indian, making it the steward of the second-largest collection of Native American art and artifacts in the United States.

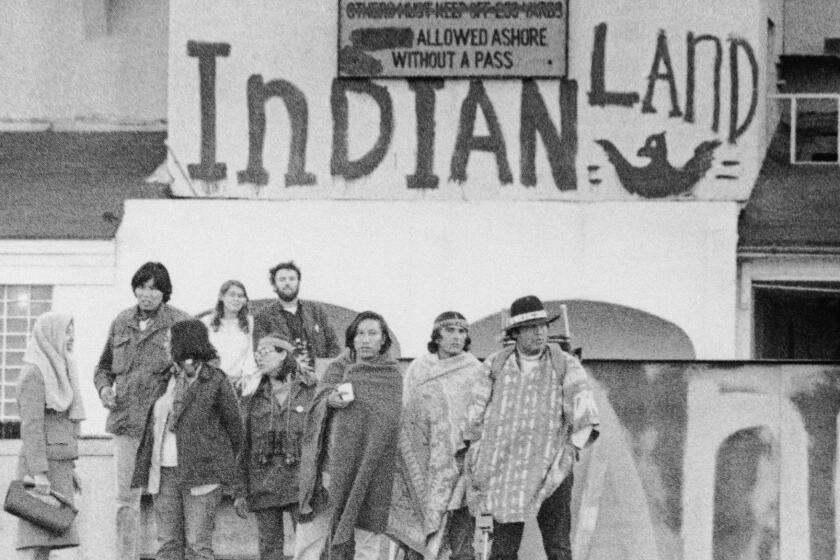

A logbook digitized by the Autry Museum reveals tribal activists and celebrities who came to Alcatraz during a 19-month occupation that began in 1969.

In 2010, McKay became the first Indigenous person to serve as chair of the Autry’s board of trustees.

“To come into this position is outstanding for a Native American,” he told The Times’ Mike Boehm upon being appointed. “One of my goals as chairman is to bring those perceptions along, so it’s not just a ‘cowboy museum,’ but a museum of the American West.”

West said that McKay was key to expanding the Autry’s vision to be more inclusive of Indigenous and other histories.

“When he came on board, they had brought the Southwest collection in and it was about telling the stories of all the people of the American West — the Autry was ready to move,” West said. “And I think it was Marshall who led that. He led that evolution.”

Marshall McKay was born June 5, 1952, in Colusa, Calif., to Mabel McKay, a renowned Pomo teacher and basket weaver, and Charlie McKay, who was of Wintun heritage. Marshall studied at UC Berkeley and Sonoma State. He later served in the U.S. Navy, helping maintain nuclear submarines.

He became involved in tribal politics in 1984, serving first on the Yocha Dehe Tribal Council, followed by a decadelong stint as chairman. After the federal Indian Gaming Regulatory Act was passed in 1988, he was instrumental in working with the state of California to develop the tribe’s gaming operations.

Beyond his own community, McKay worked tirelessly to support broader Indigenous causes. He served as a member of the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change, and he was a central figure in the ongoing effort to establish a California Tribal College, an initiative to educate Native people from throughout the state. On the cultural front, he had long campaigned against the use of Indigenous symbols as mascots in sports.

“It really is racism,” he told NPR in 2014, “and I think it’s time to talk about it from the Native perspective.”

He joined the board of the Autry in 2007 and remained involved even after his term as board chair ended in 2016. McKay was instrumental in getting West, who had previously served as director of the NMAI (and had already retired), to take over as director of the Autry, after a previous director abruptly stepped down in 2012.

McKay and Rogers McKay, his wife of almost two decades, were important collectors of Indigenous artifacts. It was he who acquired and preserved a logbook that was signed by thousands of activists during the Indigenous occupation of Alcatraz in the early 1970s — a book that one scholar described as a “holy grail” of Alcatraz research and which the Autry made available to the public in the fall.

“It’s an important part of the history of the West,” he said in an interview with The Times, of preserving Indigenous history. “The story needs to be told.”

The longtime Claremont Graduate University professor was known for vivid paintings and tiny, dollhouse-like dioramas of human drama.

In 2018, the Autry opened an exhibition that explored the work of McKay’s mother, Mabel, who in addition to being a celebrated basket weaver had also been an important advocate for Indigenous knowledge and artifacts in California. Like her son, she too served on the Native American Heritage Commission — appointed by Gov. Jerry Brown in 1976.

West said the installation at the Autry included a sound piece in which McKay talked about the legacy of his mother. “It was so powerful,” West said. “You realized from whence this man came. It was not only in his DNA, but everything around him.”

McKay, West said, understood something critical about culture — that “cultural preservation was the preservation of the community itself.”

Besides his wife and stepson, McKay is survived by another stepson, Brendt Rogers, his stepdaughter, Hsin-Neh Rogers, and her daughter, Chyna Peeler. McKay is also survived by his sister, Harriet Roberts, and Dillon McKay, a son from a previous marriage.

A service is being planned for a future date.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.