For Netflix’s “The Forty-Year-Old Version,” writer-director-star Radha Blank channeled the frustrations of a career in theater into her first feature film. Chief among them: the white producer who helps her on-screen alter ego debut a play on Broadway. This gatekeeper’s less helpful notes include saying her piece isn’t “Black” enough, requires a white character to “grab the core audience” and would be perfect for a white director who just staged “A Raisin in the Sun.”

“Some people think he’s a caricature,” said Blank, who based the producer on various New York artistic directors and raps about programmers’ affinity for “poverty porn” in the movie. “With these predominantly white male gatekeepers, it’s the same kind of person making the same type of choices, controlling what kind of diverse stories are told. There needs to be more of an investment in trying to make the American theater reflect what America looks like.”

That character is instantly recognizable to any Black playwright who has had to navigate anti-Black behavior in order to even entertain a career in the American theater. “It’s become so nuanced and harder to pinpoint that the person being oppressed has to ask themselves, ‘Wait, did that just happen?’” said Donja R. Love.

“And then the way in which you’re gaslit as an artist, you wonder, are they right? You begin to second-guess your own intuition,” added Lynn Nottage. Meanwhile, these gatekeepers “don’t remember what they’ve done because they don’t have to, because it is the Black artist who has to hold the trauma,” said Robert O’Hara. “I have held on to it for years and years and years. I’m done holding it, I don’t want it anymore.”

The movie’s release transpires as numerous industries reckon with systemic support of white supremacy. Or, as Lee Edward Colston II put it, “in the year 2020, when white people discovered racism for the first time.” However, said Jocelyn Bioh, “This pushback against the whole system — these are conversations that artists of color have been dying to have for years.”

With “Forty-Year-Old Version” now streaming, The Times invited 40 Black theatermakers to share their own experiences with insidious racism — sometimes subtle, other times blatantly cruel even amid the Black Lives Matter statements issuing forth industrywide.

RADHA BLANK

Writer, director and star, “The Forty-Year-Old Version”

For a long time I had no idea why so many theaters told me, after reading three or four of my plays, “We love your work, but we can’t produce it. What else do you have?” I heard that over and over again; it was so frustrating and made me doubt myself. What I think they meant was, “Do you have any plays with white people in them? Or will help our white patrons feel better about being white?”

It’s not to say that these places don’t produce theater of color, but it’s usually a certain kind of piece that caters to the “white with silver hair” patron and their idea of Black life. They’re rarely contemporary, and they’re drenched in strife, grief, poverty and pain, or atoning for some guilt they may have. And it shows up during Black History Month or in response to racial tension in the world. But if I were to say that the choices they made are based on racism or white supremacy, they’d turn red and be so offended.

Now I’m grateful for the adversity that I experienced trying to get my plays produced, because it gave me this story to tell.

The Netflix comedy “Forty-Year-Old Version” won a directing prize at Sundance for breakout creator Radha Blank, who also wrote and starred.

MARGO HALL

Artistic director, Lorraine Hansberry Theatre

One of my early directing gigs, I was told, “We’re concerned our audience won’t understand what they’re saying. Can you help with that in some way?” I was like, “What are you talking about? They’re speaking English. And you all just did an Irish play; were you worried about your audiences dealing with those accents?”

Eventually, we came to an understanding and it was a real learning moment for the institution. But I had to fight and say that I wasn’t going to change anything. This is a play about Black people — that you picked! — and everyone is speaking English. And if your audience needs to look up a word, then that’s work they can do.

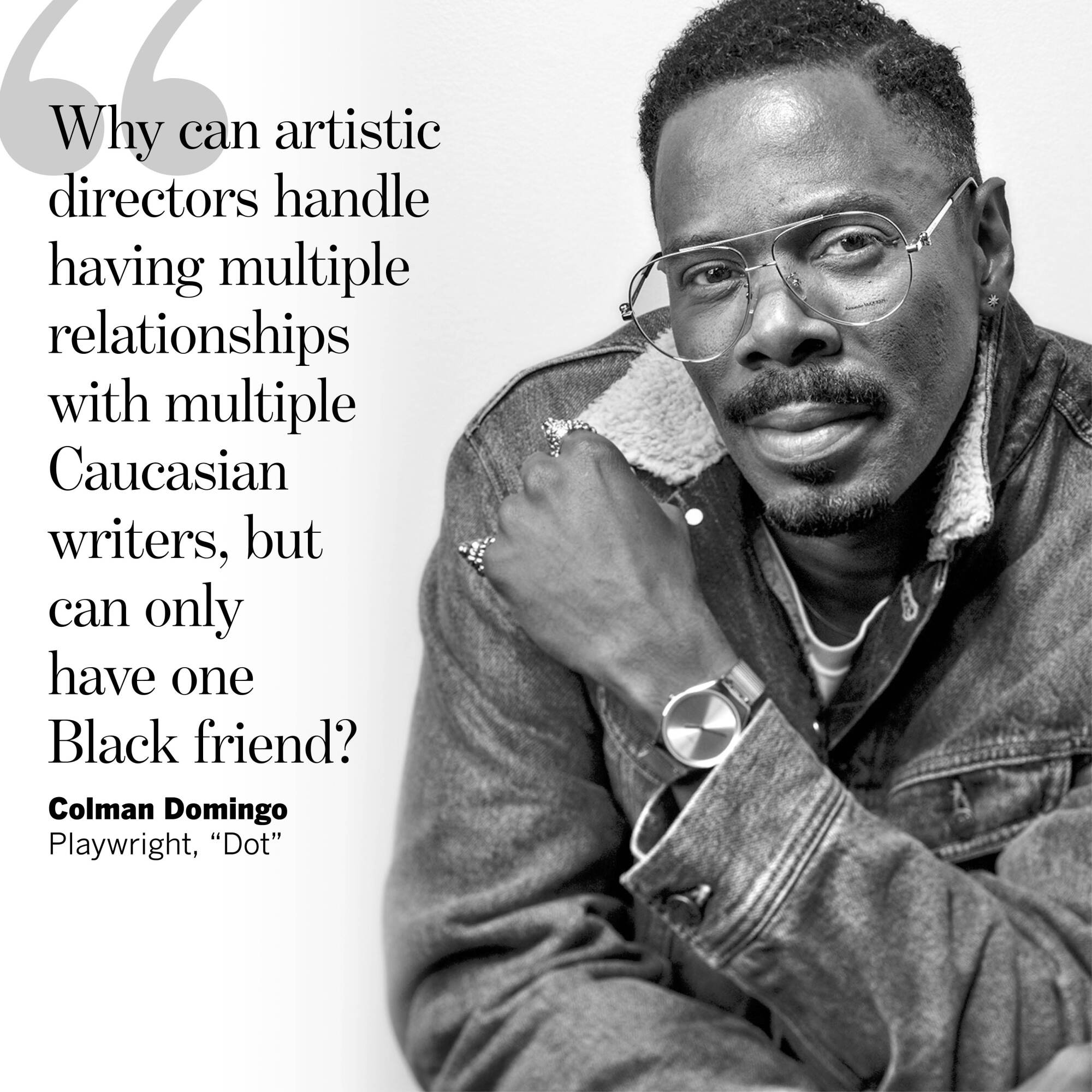

COLMAN DOMINGO

Playwright, “Dot”

I don’t take it personally when a theater doesn’t read my plays; that’s from the sheer volume of work in the world. What I do take personally is when I’ve done productions at major off-Broadway or regional theaters and afterward, it’s hard to get them to return my calls, to read new material or even watch B-roll. Generally, artists have gratitude for institutions, but it doesn’t seem to go the other way for the Black playwright in particular.

I don’t say this with any bitterness: To me, it seems that theaters are always looking for the next Black thing, and they can only embrace and elevate one Black voice at a time.

Why can artistic directors handle having multiple relationships with multiple Caucasian writers, but can only have one Black friend? My white counterparts are constantly produced at these theaters; they can fart out a play and it gets considered after a first reading.

It feels like we’re a bit more expendable. I think that’s why we’re losing a lot of Black playwrights to spaces like film and TV. I love the theater, but I’ve had to make other choices to be happy and be paid my worth.

PENELOPE LOWDER

Playwright, “West Adams”

One of my first short plays was about a wealthy African American couple whose marriage was crumbling due to a lack of communication. They were in their 50s and dining at a restaurant — one of their favorite pastimes — and often spoke in food metaphors. Easy, right?

The director told me he was having problems with casting. I compromised by changing the male character to white, but I kept the woman Black. He then told me he hired a white actress. I told him I specifically wanted this piece to be a vehicle for at least one Black actor; he said he tried but just couldn’t find any. He ignored my voice and vision. Feeling as if I had no other options, I foolishly acquiesced.

My characters went from being two African Americans to two white people. This director didn’t realize the significance of a play with two people of color who were not oppressed, impoverished or polarized. These were three-dimensional characters representing a world not often seen in theater. I never saw the production, and if I had gone to see it, I still would not have seen my own play.

ROBERT O’HARA

Director and playwright, “Bootycandy”

An artistic director in Portland told me, “I love your work, but I just don’t have the courage to do it.” This white man, with his privilege and his multimillion-dollar theater, was othering me and essentially saying, “I like Black people, but you can’t work here because I’m too afraid of your Blackness.” And I’m supposed to feel excitement that his gaze has recognized me? As if him liking my work will feed me, clothe me or pay my bills?

Cut to a couple years ago, when I directed a Shakespeare production in Denver that broke box-office records. That theater then hired a new artistic director who, lo and behold, is the same one who made that comment. He never saw my show, but when he was asked about it in an interview, he said he’s “allergic to the use of high tech” and prefers “disciplined” work. And nowhere in the entire interview did he mention my name.

His language to me and about me was rooted in racism and, even worse, was a form of eracism. And I will not be erased, especially not by a white man sitting in his privilege.

JOCELYN BIOH

Playwright, “School Girls; Or, the African Mean Girls Play”

My play “Nollywood Dreams” is a comedy set in the boom of the Nigerian film industry. One associate artistic director said to me, “When I read about Nigeria in the newspaper, all I hear about is Boko Haram, and all of the struggles and corruption in the government there. So I’m just trying to understand why everybody in your play is so happy.”

I was stunned into silence for a moment. A lot of stories from the continent tend to be “poverty porn” narratives with war, rape, struggle — not that those stories don’t exist and shouldn’t be heard, but that’s not the only narrative of Africa. And my play wasn’t about that; it’s about the entertainment world. No one is asking why they’re not talking about political issues in “Noises Off,” right?

I calmly said, “The same way we Americans are sitting here while we’re at war with God knows how many countries, we’re still everyday people living everyday lives. Those people exist in Nigeria as well. So you thinking that Boko Haram runs all of Nigeria speaks more to your ignorance than mine.” I vowed never to work at that theater again.

CANDRICE JONES

Playwright, “FLEX”

During a Q&A talkback about my play, a white female audience member asked if I “had gone to school or something because my vocabulary was so expansive.” I’m guessing she was surprised that a Black woman with a deep Southern accent could articulate herself.

It let me know that even if white collaborators are trying to be careful about their actions, the white audience members who frequent and support these theater institutions may not do the same.

KATORI HALL

Playwright and book writer, “Tina — The Tina Turner Musical”

Early in my career, I met with a white female artistic director and her associates about a commission. I pitched two plays: one with a white woman who wakes up with a Jamaican accent, and another that’s set in a beauty shop in 1940s Memphis.

They asked me, “Which one do you really want to do?” I picked the latter, which centered the Black Southern female experience. They said, “We think what’s best for us — and possibly for you — is the play about the white woman. It sounds hilarious! We could get Julia Louis-Dreyfus!”

There were so many levels to this: devaluing the Black female experience as a worthy story, wiping off the table the opportunity for a Black woman to be the star, and eradicating the idea that I, a Black woman, wanted to pursue.

Regardless of your good intentions in trying to provide me an opportunity, you pressured me to write for your gaze because you think it’ll make more money. You say it’s because you’re thinking green, but in all actuality, you’re really thinking white.

Finishing that commission was like pulling teeth. I liked the idea beforehand, but because I knew I was writing it to appease these gatekeepers, I just got so sick of it. They never put it on, and it was a positive experience when it was done elsewhere. But because its inception came from a place of racism, I still hate it with a passion.

CHINONYEREM ODIMBA

Playwright, “Unknown Rivers”

During one production, I spent so much energy trying to get the white male director to see the nuances of the story that spoke specifically to Black women, and as there were three Black women in the cast, this felt very important. Whole conversations about why a Black female character would not go to sleep without a headscarf, and consequently would need to have one on in a scene in which she’s waking up in the morning, were the smaller but no less exhausting “negotiations” that needed to be had.

Still, the director said the story spoke to women in general, and would regularly refer to experiences based on his own mother. In the same way that people say they “don’t see color,” stories that don’t acknowledge the particulars of Black female existence effectively erase us. White directors and gatekeepers need to differentiate between notes on story and the ways in which they’re simply refusing to believe the multitudes of our existence.

PATRICIA McGREGOR

Co-writer and director, “Lights Out: Nat ‘King’ Cole”

I was once assigned to be the assistant director on a production of “Trouble in Mind,” a play about racism in the theater world. I was the only Black member of the production team. On the first day of rehearsal, I asked the director — a white female — where in the room she felt most comfortable with me sitting. She pointed to the door and said, “Outside.”

TRACEY SCOTT WILSON

Playwright, “The Good Negro”

I was the only person of color in a play development program, which was putting on scene readings in front of an audience. My play is inspired by the civil rights movement; there are characters who resemble Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Coretta, and Ralph Abernathy and his wife Juanita. So the scene calls for two Black men and two Black women.

I showed up and looked around the room. I saw a couple of Black male actors, but I didn’t see any Black female actors at all. I kept thinking, these Black actors were gonna come out of somewhere, maybe they were just late or something! It comes around to my turn, and two white women started reading for the two Black female characters. I actually felt sorry for those women at one point because they so clearly wanted to die; they were speaking in such a whisper because they just didn’t know what to do.

I was in such disbelief; we’re in New York City, and they couldn’t find two Black female actors? Everyone else’s plays were cast just fine, because their characters were all white, right? I quit the program the next day.

If you want a real change in programming, you need to have a real change in leadership. And not some brand new special position for you to just hire a person of color, like everyone is doing now.

STACEY ROSE

Playwright, “America v. 2.1: The Sad Demise & Eventual Extinction of the American Negro”

I’m in Minneapolis. A New York theater company was really excited about my play “As Is: Conversations with Big Black Women In Confined Spaces.” I get myself over there, we put together a stellar cast and the reading goes very well, but the artistic director — a white male — is just sitting through it. A couple weeks later, they tell my agent — not me, my agent — that “the play does not deliver on its promise.” I’m still trying to figure out what my play about big Black women promised this cisgendered white man and didn’t deliver!

That’s at the crux of everything: The tastemakers do not live a Black experience, but still get to decide what is or isn’t a Black story. The people who greenlight things don’t understand us, and aren’t even willing to trust us to understand ourselves. I hope we’re beginning to enter a time when those opinions and decisions can come from someone other than a white man sitting behind a desk.

The Times interviewed nearly two dozen Black entertainment industry voices, spanning directors, producers, writers, designers, agents and executives. They discussed racism in Hollywood, what needs to change and their frustration with years of talk and little action by powerful companies.

JAMES IJAMES

Playwright, “Kill Move Paradise”

Very early in my career, I had spent a lot of time preparing for an audition for a play. When I went in for it, they said to me, “You’re not very urban, are you?”

It was utterly disorienting to hear someone use such coded language. And I remember thinking, “Well, do you have a note? Are you gonna do your job and offer me something to get closer to the thing you’re looking for? Because I am a trained actor, so I can play anything!”

I was able to muster some version of, “I don’t think I know exactly what you mean by that,” but in a tone that hinted that I knew exactly what this director meant. I did not get that job, and I didn’t get called in to audition for that theater for many years.

I say it out loud and know it’s small potatoes compared to what so many others have dealt with. But it truly framed how I approach my work as a director and a playwright, and what I demand of the people I work with: Try to see the brilliance of the artist, instead of making a value judgment about the person.

NAMBI E. KELLEY

Playwright, “Native Son”

Last year, I had a situation with a theater that commissioned me to adapt a play from the early 1900s that would go straight to production. But the play they handed me was not conceived with Black people in mind, not even close, even down to the fact that there was a noose in the script. The theater did not consider what that would mean to me as a Black creator.

Still, I took the work and reimagined it, centering Blackness and Black liberation through a Black female lens. They pulled the play without providing me any development or a dramaturg, which was included in the initial contract. They just pulled the play.

ERIKA DICKERSON-DESPENZA

Playwright, “Cullud Wattah”

As a 29-year-old Black woman, I repeatedly have the same encounter with theaters across the country, often led by older white male figures. They always encourage me to work with an older director — usually, the same five Black directors who direct all the major shows. They say, “Your show is going to be reviewed, so you might want to think about working with someone who’s done this before.”

That doesn’t allow for young, Black women, including trans women directors to get a foot in the door, or to forge long-term artistic partnerships with playwrights.

I want to work with someone who is closer to the demographic I’m writing about and is exploring these themes and ideas differently from previous generations, but I’m told those directors don’t have enough experience — how can they, when you never give them a chance?

It’s my greatest frustration because male collaborators seem to go forth unchallenged. So I have to make ultimatums around having young Black women directors under the age of 35. I risk it every time; it’s that serious to me. Do not insult the creativity, ingenuity and vision of young Black women.

VINCENT TERRELL DURHAM

Playwright, “Polar Bears, Black Boys & Prairie Fringed Orchids”

I had a standing-room-only staged reading of my play at a Los Angeles theater. The audience’s reception to the work was tremendous, and the robust talkback afterward confirmed the laughter and tears I had heard in the dark weren’t imagined.

But the first words out of the artistic director’s mouth were, “I wouldn’t know how to market this play.” Hindsight tells me he was really saying he didn’t see himself onstage with my cast of four Black actors, or in the diversity of the sold-out audience. I sat through him ripping the play apart, telling me the audience of 80-plus people were wrong, and continually use the word “Ebonics” rather than eugenics, which is a topic in my play. A few emails flew back and forth after that, but they never produced my play.

That same artistic director has since emailed me, apologizing for what he did and praising my work. I still haven’t replied to that email. I appreciate it greatly, but there’s no victory in simply the acknowledgment of racism.

KEENAN SCOTT II

Playwright, “Thoughts of a Colored Man”

I’ll never forget one of my first meetings about my play, when I was told by a white producer, “I don’t know if a story about seven Black men is commercial enough.”

I feel like my white counterparts are never asked: “Will these seven white men be commercial enough? Will they sell tickets? Will this be palatable for audiences — who, typically, are middle-aged white patrons — to receive it?”

In that moment, I was told that the Black voice is not the standard, that stories from my community are not human stories. And we have to water down our Blackness to cross over to a “wider audience” because being authentically us is not enough to do so.

Of course, I didn’t work with that producer, and that play is Broadway-bound next year. I hope the gatekeepers of American theater understand that by seeing the value in stories about different types of individuals outside of those who are white and male, they can redefine who that standard ticket buyer can be.

PIA WILSON

Playwright, “Turning the Glass Around”

I was working with a theater’s public relations representative to put together a press release for my show. Upon discussing the themes of the play, she asked me, point blank, “Why would white people care about that?” I’m rarely flabbergasted, but I was on that day. Worse, I was diminished as an artist.

I told her that stories featuring Black people can be universal, and that people of color have been going to all-white shows for decades without anyone questioning if those stories were universal from their points of view. She dutifully wrote down what I said, but none of it wound up in the press release.

White people are so centered in American theater that this woman really thought she had asked a reasonable question. It made me sad when I realized that at least she asked this question to my face, whereas literary managers probably asked themselves this same question whenever they read my work. To really make a change — and to survive —American theater is going to have to put more BIPOC in the decision-making process.

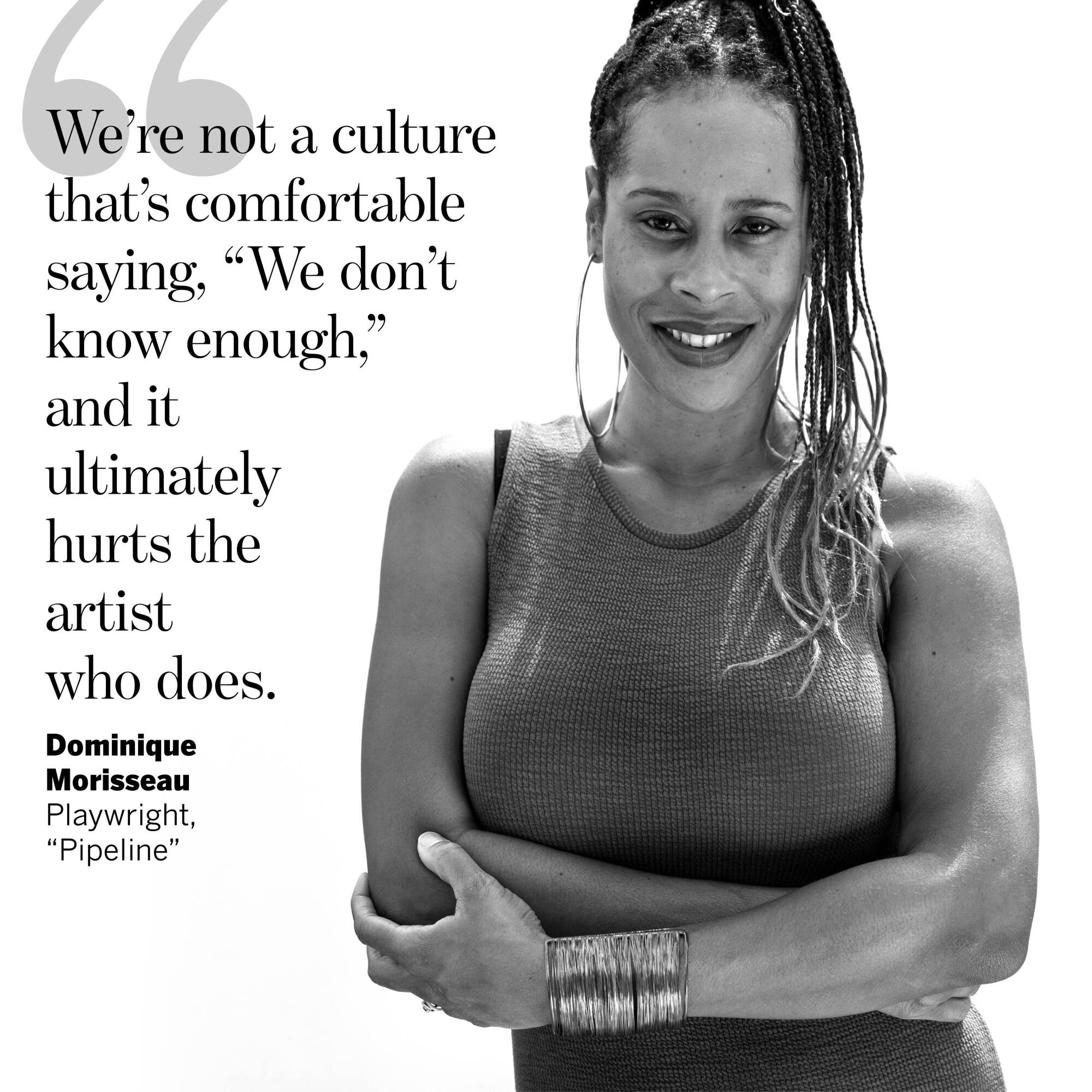

DOMINIQUE MORISSEAU

Playwright, “Pipeline”

Let’s talk about the white critic gatekeepers, who don’t seem willing to step back and acknowledge that they’re not the expert on something. They’re the people who don’t even know the people you’re writing about, but then they’ll tell you how well you wrote about them.

When “Detroit ‘67” was done at the Public, one character was likened in an insulting way to “Good Times.” It felt like someone was trying to tell me that I’m caricaturing and exaggerating my family, my community, my own people — people you’ve never met, never had a conversation with and never been invited into the homes of. We’re writing from our real lives, but the critic has no idea of what those experiences are like, and then their review misses the work because it just has no context.

That then becomes how my work gets etched into the cultural canon, and that’s completely ridiculous. What’s even worse is that the work doesn’t go forward because the theaters are way too obedient to these critics. We’re not a culture that’s comfortable saying, “We don’t know enough,” and it ultimately hurts the artist who does.

DONJA R. LOVE

Playwright, “One in Two”

My play is about how one in two Black gay and bisexual men are projected to be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime, and the end is a call to action to stop this hidden epidemic. During previews, my director and I were talking to the artistic director and associate artistic director, who said that folks loved the play, but felt as if they were being yelled at.

I very candidly asked if they were referring to white people. I told them, “This play is for everybody, but it’s specifically for Black gay men to see themselves centered. This note, though, is essentially centering white people; it’s a note about culture, not craft. If you have a note about structure and making the work the strongest it can be, please give it. But this is not.”

I’m sure they weren’t thinking about white supremacy in that moment, but they listened, understood and shifted for the next time we spoke about the play. That’s how we can fix this. I’m not interested in allies, who can go back into their privilege at any moment. I’m interested in accomplices, who will stand alongside you when s— goes down.

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins, Jackie Sibblies Drury and Jeremy O. Harris lead a new era of theater demanding that audiences confront the truths in front of them.

STACY OSEI-KUFFOUR

Playwright, “The Pearl in the Black Sea”

When you’re a POC playwright, theaters will blame it on so many things — their company members, their subscribers, timing — because rarely are they willing to take a chance on your work and on you.

When George Floyd was murdered, a white theater company in Los Angeles reached out to me, after promising me to produce my work for four or five years now.

Why does it take a horrific event, like a man being suffocated and killed by police, for this theater to finally produce my work, for me to finally be seen and considered?

I ultimately said no to this theater, and unremarkably, have watched them continue to only produce white plays.

[The idea that] white stories always come first is ingrained in our culture, our society and our systems, and it’s wrong. I want other stories to have priority, to have the chance to truly shine.

We have so much to say, and if we’re given the platform and the space and the time — beyond our race — we could and would succeed.

FRANCISCA DA SILVEIRA

Dramaturg and playwright, “can i touch it?”

This moment is still so visceral in my mind. It was my senior year at New York University; I had a playwriting thesis class with one of my best friends, also a Black femme playwright. Our professor, a white woman, often confused us for each other, and even went so far as to email us the other’s script notes. We look nothing alike, nor were our plays similar in terms of theme, structure or story. But none of that seemed to matter.

Reflecting back, I realized we were being lumped together into the monolith that is “the Black play.” Having since taken part in conversations around play selection and programming at predominantly white theater institutions, I now know that the concept of “all of us looking alike” isn’t just attributable to physicality, but also our artistry.

Not only are we not a monolith, but the play selection process as a whole needs to change. Theaters need to examine who is doing the reading, who is saying “yes” and “no” at all levels. Having one Black play in a season is not enough. And Black plays are no riskier to produce than white plays.

ALESHEA HARRIS

Playwright, “What to Send Up When It Goes Down”

I was part of a collaboration between theaters in California and France. The director, a white Frenchman, wanted to explore topics like race relations in America, but oftentimes I was the only Black person in the room. He fired people whenever he felt challenged, and because I voiced my concerns, he barred me from rehearsals.

This director, with the artistic director in California, read my private emails aloud in a meeting, and colluded to make me look like I was lying. It was disheartening and frustrating that these two white men in power understood that cultural mythology allows them to be more believable than me, who is both Black and a woman.

Of course, this theater recently released a Black Lives Matter statement. You’re not shooting Black folks in the street but, when this happened, you essentially were telling me my Black life definitely doesn’t matter.

The theater world fancies itself as very liberal, but there are ways in which it replicates the very things it seems to disdain in our current administration. Your theater can’t simply say “Black Lives Matter.” You need to actually care about the Black lives in this industry.

JOY YVONNE JONES

Playwright, “Ode to My Mothers”

I was cast as the primary love interest in a production of a play that was considered a “forgotten gem.” This play was racist; it’s a slave to the time in which it was written. Due to unconscious bias, the wealthy characters in the show were played by white actors and the poor characters were played by Black actors.

Even more so, the phenomenal actress who played my mother and I were constantly compared by the director to a recording of the production performed 20 years prior. It didn’t matter what we brought to the table. It was clear that they wanted our Black faces to perform the characters with the whiteness to which they were accustomed. A performance that would keep their audience comfortable while simultaneously checking the diversity box.

I take pride in the work that I do and the characters that I have the opportunity to bring to life. Our experiences as artists of color provide seasoning for the characters that we embody. Theaters shouldn’t see this as an obstacle, but as an opportunity to enrich the stories we’re telling. If I’m cast with the expectation of performing whiteness, then I’m asked to omit authenticity.

DAVID E. TALBERT

Playwright, “The Fabric of a Man”

A promoter said the title of my 10th play was “a bit esoteric” because of the metaphor, and should be changed to “something that the audience can wrap their minds around.”

He then suggested titles that felt like blaxploitation episodes like “Things Your Man Won’t Do” that really speak down to the African American audience.

I trust my audience because I am my audience, and we as a community can embrace and “wrap our minds” around all kinds of concepts and metaphors and ideas. The Black audience needs to be given the respect they deserve, and our art needs to be given the respect it deserves. I didn’t change the title, and it ended up being the biggest in my catalog.

FRANCE LUCE-BENSON

Playwright, “Deux Femmes on the Edge de la Revolution” and “Boat People”

I was the only Black playwright in my graduate program. A year before I was to write my thesis play, and long before I had even conceived of the play, I was asked to write a two-hander. Not because it would provide me with an opportunity for creative growth and development, but because the department would be producing “The Piano Lesson” next year and once it was cast, there would only be two Black actors left for me.

At the risk of being labeled as “problematic,” I challenged this request and ultimately wrote the play I wanted and needed to write, and requested the department hire professional actors to round out my cast, which they did. What I noticed then, and many times over in my professional career, is what I guess I’ve always known about being Black in America: I will always be faced with more obstacles than my white (and often male) peers. As an artist, I must be thick-skinned, and with the stamina to repeatedly get back up after getting knocked down, yet vulnerable and open to tell the truth in my work.

REGINALD EDMUND

Playwright and founder of Black Lives, Black Words

Black Lives, Black Words is a grass-roots initiative dedicated to developing and producing new plays by Black writers from around the world. To reposition themselves at the forefront of the Black Lives Matter movement and to generate funding, organizations have been quick to use the BLBW name and list the multitude of talented writers that have graced their stages, thanks to our play festivals.

However, it’s surprising that the work that I write, as well as the artists I produce through BLBW, still struggle to find seasonal artistic homes at these regional theaters. The work is either deemed too Black, too political or fails to bag the season’s sole spot for “the Black political play.”

DAAIMAH MUBASHSHIR

Playwright, “The Immeasurable Want of Light”

I had an internship with a well-known, well-loved “downtown” off-Broadway theater in New York City. The literary manager made a big show of making me feel welcome, and as an ambitious artist I was hungry for that attention. It felt like he was taking me under his wing: He had me read plays, attend shows with him and spoke openly with me about what was “smart” and what didn’t work. I remember his eyes glazed over when I asked him about theater focused on Black stories. He advised that, except for one or two, plays about race usually get too preachy and melodramatic, which never do well in New York City.

Up until that point, I had seemed quiet and agreeable and happy to be paraded with him from introduction to introduction in theater lobbies. When he asked me to share my ideas and career visions, his demeanor chilled and the outings ceased. During my exit interview, his advice for my career was flat: “I don’t know. Theater is finicky.”

This man still emails me once or twice a year: “How’s your work going? Are you getting the attention you so deserve?”

LEE EDWARD COLSTON II

Playwright, “The First Deep Breath”

A well-intentioned white woman was offering feedback and notes on my play. She came in with declarative statements like, “We think your play could be funnier.” And it’s like, “My play is funny, but the jokes are Black, and Black actors will know how to do that. Don’t say the play isn’t funny, just say that you don’t get the humor.”

Whenever she gave me notes, I was resistant not because of the content, but the blind spots of her approach. We ended up having a real conversation about it — acknowledging the power dynamics of me being a Black person with contracted work, and her being a white person with the institution — and she listened, asked questions and apologized.

Things shifted after that, but it put a lot of undue emotional labor on me to educate, with compassion, this woman so that I’m not feeling unsafe while trying to create something. It’s a skill I have as a result of navigating America while Black. Otherwise, I wouldn’t work.

Patti LuPone, Lynn Nottage, Tarell Alvin McCraney, Young Jean Lee, Joe Mantello and others answer the question: How should theater be different?

JEREMY O’BRIAN

Playwright, “under one roof; or home to mississippi”

Theater in my experience seems to operate under the guise, whether consciously or unconsciously, that new Black playwrights “should just be happy to be in the room.”

I had a meeting with a regarded literary director who agreed to meet with me and scheduled the meeting around their convenience. When we sat down, they revealed that they had not read my work yet. But they would!

They then went on to discuss with me the work of another Black playwright whose work they had most recently developed and produced.

LOY A. WEBB

Playwright, “His Shadow”

My play is about a football player who becomes an activist when someone dies at the hands of police. Many theaters demanded I answer whether this play was about Colin Kaepernick. I kept telling them, “Colin’s legacy is part of this piece, but it’s an homage to the history of Black athletes who’ve revolted before Colin and those who will come after him.” The play references Tommie Smith and John Carlos; a simple Google search of those names would have absolved that inquiry. Still, they didn’t seem to get that, nor did they find it important. In fact, an off-Broadway theater told me the play was “too simple.”

I think about that comment a year later, as more athletes have become vocal about the injustices in this world and, sadly, more Black people have died from police brutality. How disheartening it is to have to defend our stories, to be told that our lived experiences are “too simple.” To Black writers who are writing the world as they’ve lived and breathed: do not stop, despite the ignorance of white institutions who are illiterate to the struggles and rich history of Black people in this country.

B.B. COOPER BROWNE

Playwright, “Chicago Theatre Goddamn!!!”

It was 2017. Hedy Weiss had just released another racist review, and ChiTAC responded with a call for theaters to stop offering her complimentary tickets to opening nights. I sat in a staff meeting, led by Goodman Theatre executive director Roche Schulfer and artistic director Robert Falls, waiting for the moment we’d discuss the institution’s statement on the matter — released late and without staff input.

But the meeting was about to end without any real challenge to leadership’s decision to uphold systemic racism in theater. I was shaking with rage and fear, but I knew that none of my white colleagues were going to break the silence of stifled dissent. I was a young Black playwright in an entry-level marketing position — in other words, vulnerable as hell — and yet I felt responsible for forcing these two powerful white men to answer to me and my community.

I broke down why the theater’s statement upheld racism and white supremacy, and though it sparked an hour-long discussion among staff, the following days were marked by various gaslighting tactics from upper management. A week later, I quit. And it hurts to know that not much has improved since I left.

INDA CRAIG-GALVÁN

Playwright, “Black Super Hero Magic Mama”

While working on a world premiere, I had a conversation with the actors about making sure Black people were in the audience for this Black play. We knew this theater’s core demographic didn’t include many people who looked like us. I then remembered that I used to work at a theater in Chicago that always had matinee performances when the house was completely bought out by a Black fraternity or sorority.

I suggested this to the marketing department of the theater producing my play. They responded with, “Great! Can you give us those contact emails and phone numbers?” No, I cannot. Because that’s not my job. I wrote the play. Your job in sales and marketing is to establish relationships with organizations that might not look like your typical audience — if you’re serious about diversity and inclusion.

I don’t think they ever reached out to anyone.

SHARAI BOHANNON

Playwright, “Why Are You Like This?”

It bothers me that plays in which Black people have joy are tossed to the side. I held multiple jobs in Chicago and was always appalled at how theaters will take anything from white playwrights, but when a Black playwright submits something that isn’t steeped in trauma, it “doesn’t say anything.” But our white counterparts can send characters into space, relish in writing basic femmes who brunch, and are giving the chance to experiment and fail.

Why are Black playwrights only allowed in with the play that we don’t want or need? I want more Black characters who aren’t constantly crying or dying a tragic death to show Karen that racism is bad. Karen should know that already, and I should be able to enjoy theater without being triggered.

I recently removed one of my plays from consideration from a season that was turning out to be a list of Black trauma plays. I pointed out how this is an awful practice, and they ended up listening to me, and I’m so happy. Their season doesn’t let their audience get away with thinking only Black “trauma porn” plays have merit.

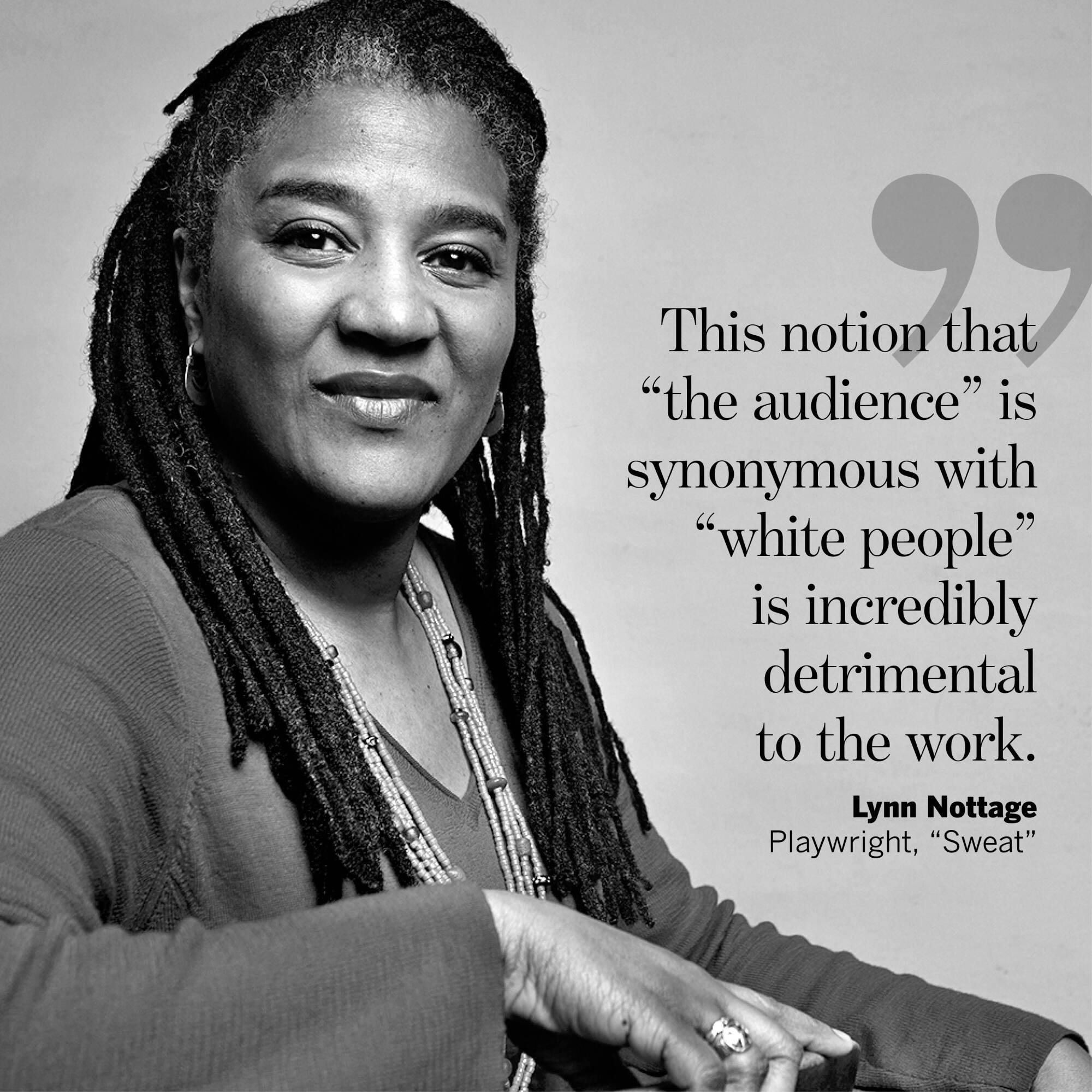

LYNN NOTTAGE

Playwright, “Sweat”

I wrote a play that did not have any white characters, and I remember the literary manager saying to me, “I think this is great, but you need to have a character that allows me entrance into your work.”

That is not the first and only time I’ve heard that as a note from either a white dramaturg or literary manager, whose job is to help the playwright get closer to their own voices, not further away. I did consider adding the character, and then decided not to.

This notion that “the audience” is synonymous with “white people” is incredibly detrimental to the work. But when you’re a BIPOC theater artist working in predominantly white institutions, you wonder whether, in order to succeed, you have to reshape, alter or craft your voice in such a way that allows an audience, who might not necessarily be invested or familiar with your narrative, entrance into your work. It speaks to the anti-Blackness that’s been so pervasive throughout our predominantly white cultural institutions for many, many years.

DAVE HARRIS

Playwright, “Tambo & Bones”

At a play development conference, playwrights are supposed to cast your play read-through with the actors in the room. It’s a model that operates on the assumption of, “This is what we’ve always done, this has always worked for us.” That’s because, for the most part, the conference is mostly catered to white playwrights.

That model doesn’t work if your play has six Black characters and almost no Black people in the room. It put me in a messy situation where I ended up at a table of mostly non-Black actors reading my Black characters. It was a full-length play — so like 90 minutes long — and it was mad uncomfortable!

Afterward I let them know that it wasn’t OK. But it’s not fair that I have to deal with that burden, that I have to worry about the safety of my entire career by bringing it up. Why is that part of my job of being a playwright, whereas the white guy just has to write his play?

MFONISO UDOFIA

Playwright, “Her Portmanteau”

I write plays that specifically focus on Nigerians in America, and try to write my characters as authentically as I know them. I never want to explain their existence, their culture and/or their choices. I want to let them just be, in the same way I see other characters just … be.

But I’m often pressured to explain myself and make my work — and sometimes even my culture — more easily digestible. I’ve had to say, “My character would never explain this aspect of their culture when talking to a fellow countryman.” You are asking me to leave the world of my play, and explain the “why” of absolutely everything for your gaze, and I won’t. My work is not a specimen. And I know, if you would just allow yourself to drown in my universe, without that explanatory anchor, an emotional reality would be revealed. That is usually enough. Why is that not enough for me?

I hope gatekeepers understand that playwriting is the conjuring of lives, not explainable events. Please ask yourselves why you’re asking me to explain something, and whether you’d ask someone else the exact same questions you asked me.

ADRIENNE DAWES

Playwright, “Teen Dad”

I expect to do my work without having to argue the validity of my ideas and abilities, or to “prove” I belong. I was directing and producing a comedy show in Austin, and partnered with a venue that publicly expressed a desire to feature diverse voices. My co-producer and I wanted to create something that paid homage to ‘90s sketch shows like “In Living Color” and “House of Buggin.”

I assumed a marketing meeting with our venue partner would be about logos and other materials. But the conversation became a question of how the show would sell. “Could it even find an audience? Was I really sure?” Essentially, “Will this Black show really sell us tickets?”

I don’t remember my answer being very eloquent, but the gist was, “Trust me. This show has an audience.” And it totally did. We sold out every performance. It won several local theater awards and became the highest-grossing show in the venue’s history. And then we moved to a large venue and sold out every single performance there too.

RAIVEN FRENCH

Playwright, “I Feed You Defiance”

Being African American and in the arts means the diversity of my culture will often be reduced to a “one color fits all” category, especially in the eyes of gatekeepers. While in college, most of the plays were predominantly white, so there weren’t many roles for Black women. If one was available, it usually went to one particular actress. This became normal to me; I thought it was only this institution and I’d just have to wait my turn to claim those coveted roles.

I came to understand that most theater companies operate under this same systemic racism. While others are seen for their diversity of looks, character and spirit, the Black woman is only seen as the Black woman. As long as you cast any one of us, the quota is satisfied, right?

That’s why I produce theater. It’s the only way to see myself in diverse and honest creations, with the fullness of Black culture. I hope the theater community can learn to appreciate us not simply as fill-ins, but individuals with rich cultures and backgrounds who provide color and dimension to many stories.

DANIEL BEATY

Playwright, “Emergency”

My first major production in the white American theater got multiple celebratory reviews and nightly standing ovations. It won an Obie — one of the highest off-Broadway honors — and was slated for Broadway. But a white male New York Times reviewer operated from such supreme privilege and dared to critique a work that he did not even understand: the expression of a young Black man who survived a journey he knew nothing about.

Suddenly, this Black boy’s dream was deferred. Not only did that show not go to the Great White Way, as it’s called, but that same theater — an institution that claims to be among the most inclusive — took a year to respond to my next script and has not since offered to produce my work.

My story is not unusual, because the nightmare that is American theater mirrors that of America, which has always been inequitable. If these white liberals are really down to create a true American theater, every white male artistic director should resign and be replaced by a person of color or a woman. Period.

But if the American theater returns to business as usual, it will be the greatest Shakespearean tragedy that many have no interest in attending. Its hero refuses to confront its tragic flaw, which will be its downfall.

Design by An Amlotte

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.