Column: Black athletes are adored — when they are in uniform

You can’t say we weren’t warned.

Some of the most influential figures in the history of this country have foreshadowed both the peaceful protesting and violent destruction that have enveloped the nation in the wake of last week’s police killing of George Floyd.

But those figures were black athletes, and white America regarded their words as little more than the ramblings of a dumb jock. The sports world could have perhaps effected the change that might have prevented the burning of America, if only America had deemed it worthy to listen.

“So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years,” said Muhammad Ali.

For that, he was exiled.

“If I do something good then I am American, but if I do something bad then I am a Negro,” said Tommie Smith after raising his fist with John Carlos at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

The main concern of black people right now isn’t whether they’re standing three or six feet apart, but whether their sons, husbands, brothers and fathers will be murdered by cops.

For that, they were shunned.

“There’s a lot of things that need to change. One specifically? Police brutality,” said Colin Kaepernick, the quarterback who kneeled during the national anthem.

For that, he was blackballed.

“Kaepernick passively protested during the anthem and he was ignored — this weekend, you got the alternative,” said Dr. Todd Boyd, USC professor of race and pop culture. “People can’t say they haven’t been told.”

It is the sad dichotomy that has defined our sports culture and delves into the heart of its prejudiced nature. Black athletes are loved when they are playing, but devalued the minute they stop.

“It’s the same with all black athletes,” said Clippers coach Doc Rivers. “When they’re wearing the uniform, they’re seen as an athlete. When they take it off, it’s a problem.”

“Shut up and dribble” wasn’t just some ignorant phrase coined a couple of years ago by conservative talk-show host Laura Ingraham.

Fact is, it’s a phrase long believed by many, even though this ignorance makes no sense in a reasonable society. After all, perhaps nowhere is the intersection of white and black America more perfect than during a sports event.

The majority of football and basketball players are black, the majority of fans in the stands are white, yet seemingly every night in gyms or fields across this country, the two disparate groups empower each other, uplift each other, and connect on a level deeper and wider than anywhere else in this fractured land.

The white fans embrace black athletes even though they look far different than them. The fans drop their popcorn and spill their beer in order to stand up and cheer for the athletes as if they were family members. They chant their first names as if they were on the same team. They bow as if they are not worthy.

The black athletes, as with all athletes, feed off the love of these white strangers. They raise their hands to inspire them. They wave their arms upward to exhort them. They say they play harder when they hear them. It is the biggest reason teams perform better at home.

Nowhere in America do differences in color and culture disappear quicker than in the three hours of a sporting event.

USC distanced itself from a booster after ‘abhorrent and blatantly racist tweets’ in the wake of mass protests over the death of George Floyd.

So how come things change so much when the games end? How come we don’t listen when these same athletes we love in the arena complain about being unloved in the streets? By virtue of their connection with a wide swath of the country, nobody’s voice can have more impact than athletes, yet nobody is disregarded quicker, and why?

“A lot of people don’t have any interaction with black culture outside of watching sports, so they see athletes as props or avatars on a video game,” Boyd said. “They don’t see their humanity.”

Fans often don’t see the players as husbands, fathers and sons. Fans often don’t see that these players, despite their millions, still live and work in a country taut with racial tension. Fans sometimes think they’re little more than shiny sports ornaments.

“They only see them as providing entertainment,” Boyd said. “There is a lack of recognition of dealing with them as citizens, as human beings.”

Rivers recalled the numerous stories of that humanity disappearing in plain sight.

“You always hear about a black athlete in a store and he can’t get service, but then the minute he’s recognized, all the employees want to give him service,” Rivers said. “When the uniform comes off, he’s not as powerful.”

That dilution of presence is felt by black athletes who often wonder if anyone is watching or listening. They are being encouraged to share their feelings by Rivers, who led the Clippers during the league removal of racist former owner Donald Sterling.

“What is happening is not new, it’s been going on for a long time, people have been speaking about these things and only a few people have heard it,” Rivers said. “But I tell people, you’ve got to keep speaking the truth, it’s worth it. Just because you’re taking the right stand doesn’t mean it’s going to be easy, but it’s worth it.”

Boyd recalls a scene that epitomized the need for those words. It occurred during a recent NBA Finals, when LeBron James was walking off the floor in front of a couple that was loudly cursing him. At some point, James turned and looked at the couple, and the change was immediate.

In the wake of George Floyd’s death, NBA players and coaches are speaking out once again about racial injustice and what must change.

“I’ll never forget the look on their face, they were so shocked, it was if in that moment, they realized they were yelling at a real person,” Boyd recalled. “This is so telling. Before that moment, to them, LeBron James wasn’t even a human being.”

When James and other black athletes talk about social issues — and this will happen plenty in coming days — white America, including me, need to recognize the humanity in those words. We need to listen. We need to bring those words back to our communities and lead.

And white America needs to continue to follow the lead of the black athletes when the protests end, when the downtowns are swept of debris and rebuilt, when the hard, inconvenient truths feel less urgent.

”The players have to lead, the coaches have to lead, the owners have to lead,” Rivers said. “The protests are going to stop, but this leadership has to survive the protests, we have to continue to be honest about slavery and the effect of it.”

We need to listen when they remind us that while we still live in a country where a cop can stick his knee on the neck of a black man until that man is dead, we never again get to say, “Shut up and dribble.”

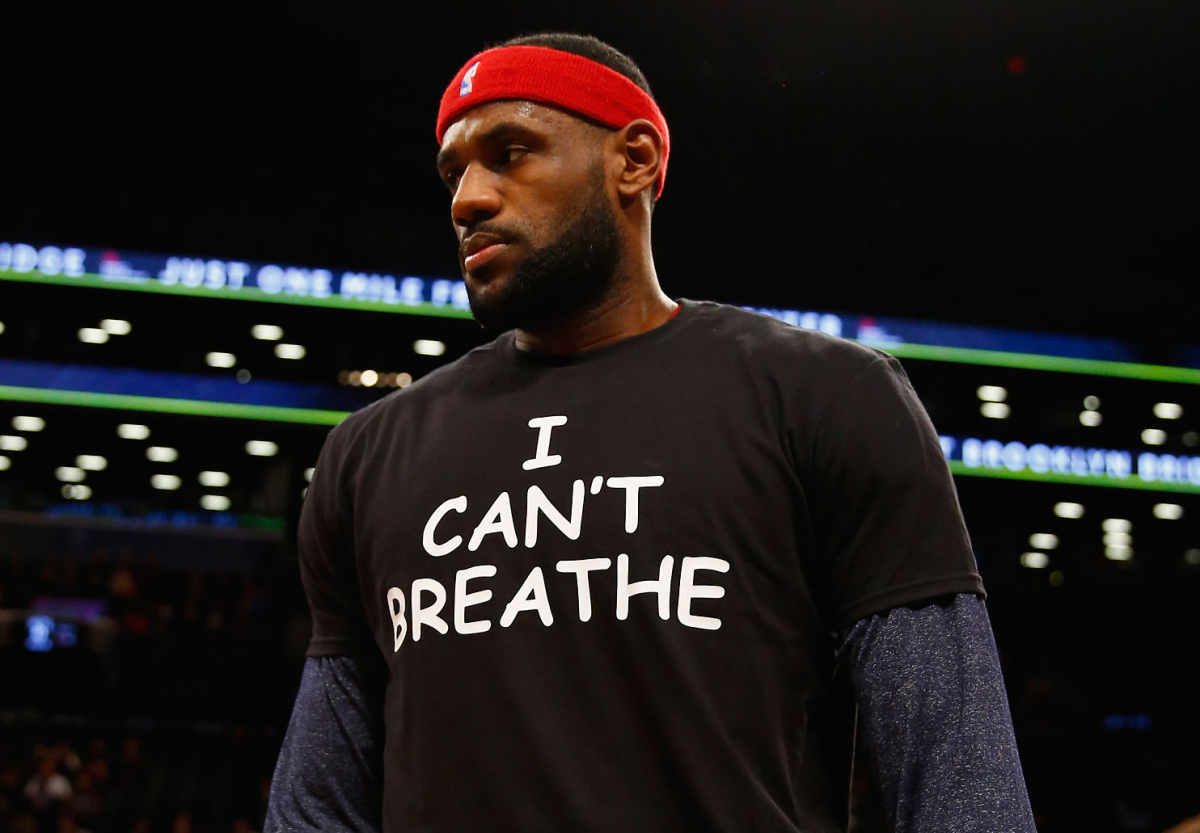

Five years ago, entire NBA teams were wearing warmup shirts that read, “I Can’t Breathe” in honor of the final words of Eric Garner when he died in a police choke hold. Horrifically enough, those were also the final words of Floyd as he succumbed to Minneapolis police offer Derek Chauvin’s knee to his neck .

You can’t say we weren’t warned.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.