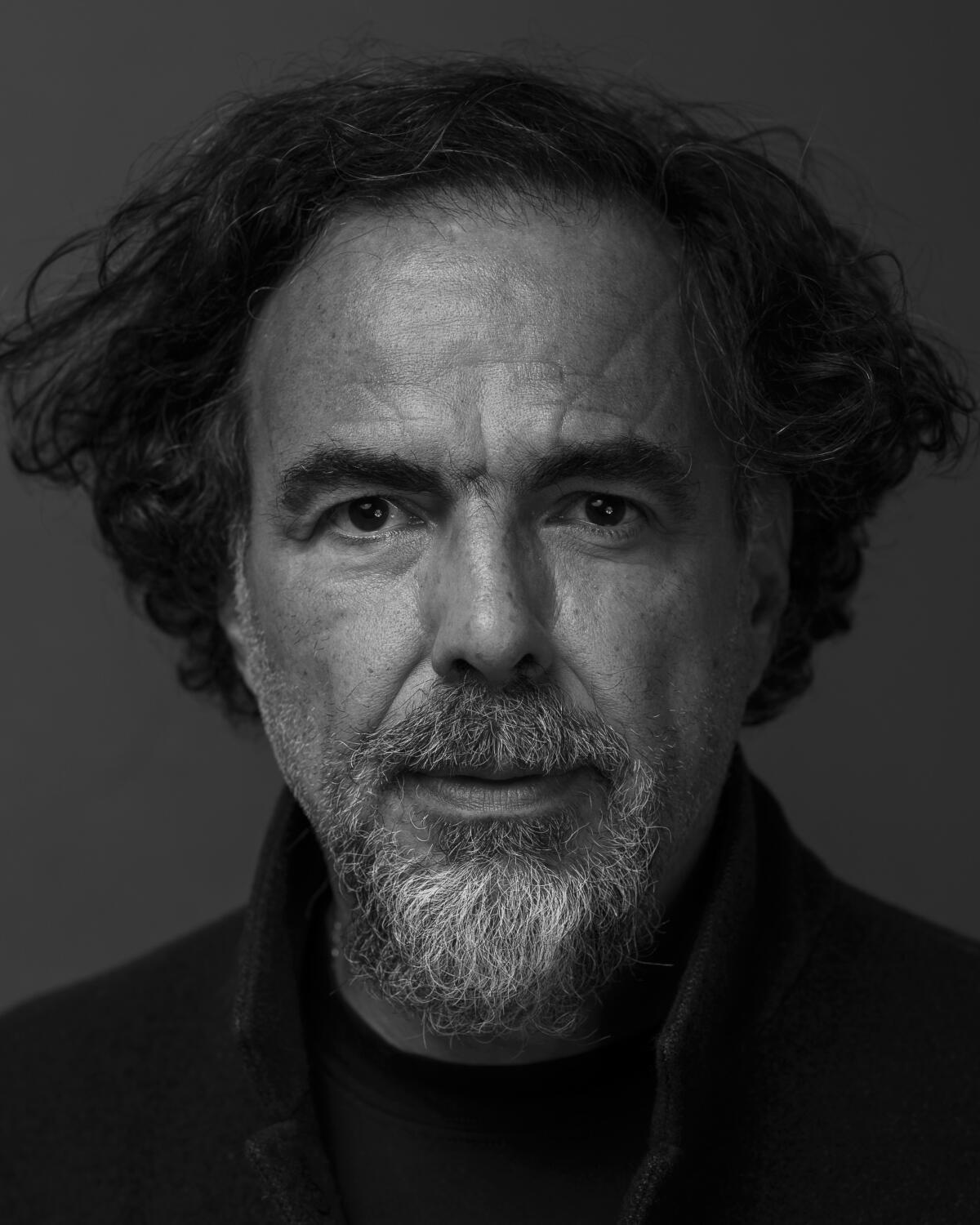

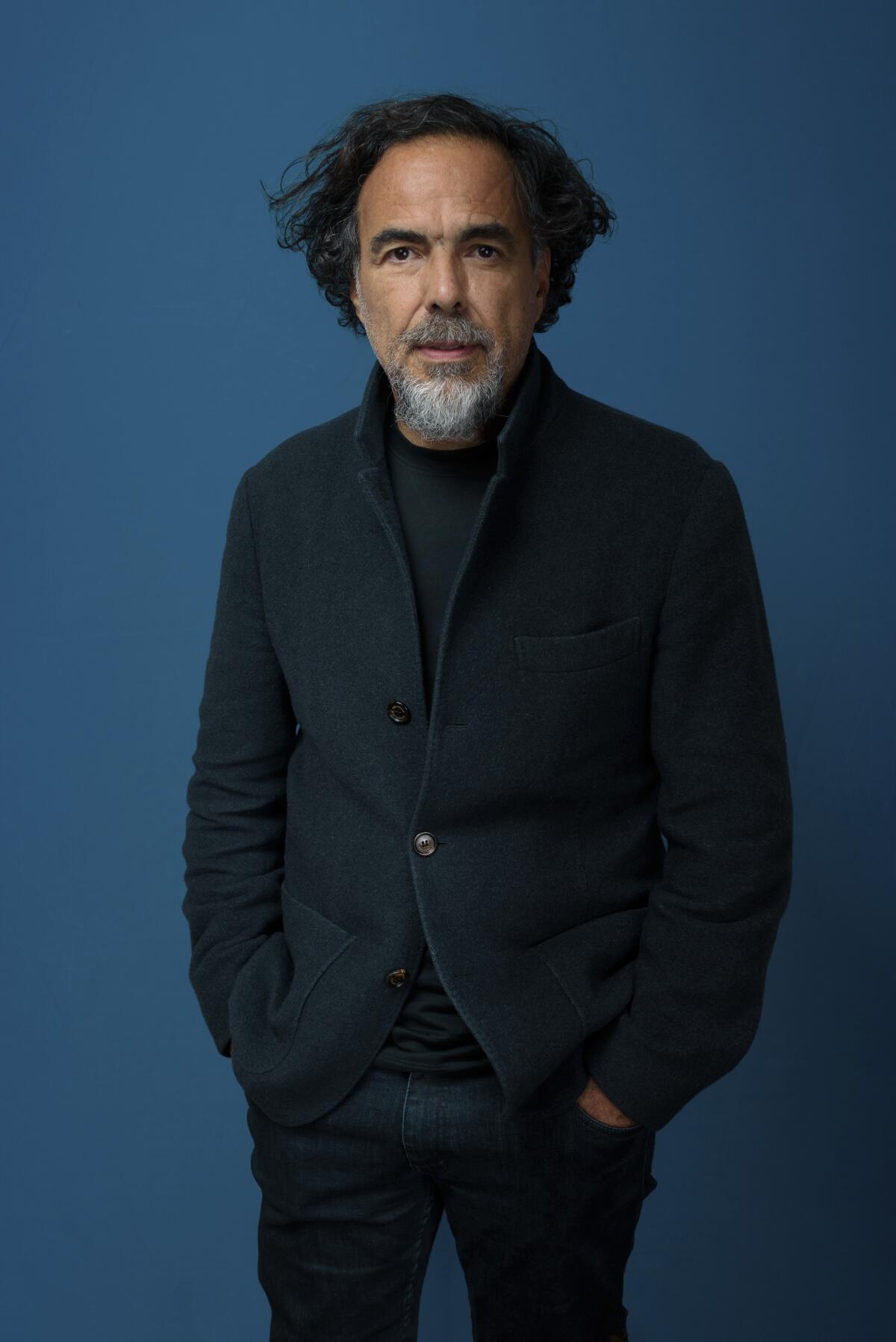

An Oscar winner opens up about leaving Mexico, being racially profiled and ‘the dual life’

“One year turned into 21.”

That’s how Alejandro González Iñárritu described the time he’s spent living in the United States during a recent interview. He was in a Beverly Hills hotel promoting his latest film, “Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths,” now streaming on Netflix.

The film, he explained in Spanish, existed “to question the narratives, mine first and that of my country, the collective one.” Iñárritu moved from Mexico City to Los Angeles in 2001, just a few years before I also left the Mexican capital as a teenager for a chance at something better up north. Nos fuimos buscando norte, as people say.

And while he’s an Oscar-winning image maker, both revered and derided, and I’m an undocumented journalist allowed to work here through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, the yearning for a homeland becomes kinship through our conversation. The understanding of what’s left behind to grow elsewhere is a common language, perhaps even more direct than any spoken one.

Immigration has served as a recurrent subject in his work, on the screen and off. And the director has actively tried to offer people like me an alternative route to belonging through ReconoceR, a scholarship initiative Iñárritu created with the University of Monterrey in northern Mexico to help “dreamers” born in Mexico but raised in the U.S., who may be prevented by immigration status and financial hardship from accessing higher education stateside.

We discussed “Bardo” not so much in filmic terms, but as an anatomy of migration that distills the essence of the experience regardless of one’s circumstances. To me, it’s not a movie about success, or even specifically about a filmmaker, but about a fragmented identity, and our futile efforts to make it whole, even if only for a few moments at a time.

Below are edited excerpts from our chat.

Trimmed by about 24 minutes, the Oscar-winning director’s surreal semi-autobiographical fantasia, starring Daniel Giménez Cacho, is worth wrestling with anew.

What brought you to the U.S.? Did the opportunity to work in Hollywood seduce you?

I’m from a generation — like Guillermo [del Toro], Alfonso [Cuarón], El Chivo [Emmanuel Lubezki] or Rodrigo Prieto — where we had to leave because the country couldn’t provide us what we needed as filmmakers. When I left Mexico in 2001, the country only produced six or seven films a year. There wasn’t an industry. I made “Amores Perros” like a miracle. I spent my own money to make it. I lost money on it. There wasn’t really a possibility for me to be a filmmaker there, which is what I most wanted to be.

The other reason, just as important, was insecurity. My dad was kidnapped, and they left him on the side of the road. My mom was robbed, and they punched her in the face because she wouldn’t let go of her purse. Every week someone close to me became a victim of crime. My children were very small, and after “Amores Perros,” I became a very recognizable figure, and that put me in an uncomfortable position, but I refused to live with bodyguards or bulletproof cars. I couldn’t live or work that way.

Did you ever consider moving back to Mexico after living here for some time?

We thought about moving back when I made “Biutiful.” When I finished “Babel” in 2006, I thought about making a movie to move from Los Angeles, but first the idea was to move to Europe, specifically Spain. And me and my whole family went to live for a year in Barcelona. It was a great experience. But I couldn’t see myself living there, the city felt too small for us. At that point, we did think about going back to Mexico. We were always seduced by the idea of returning, but our children started to make friends here, to have their lives in the U.S.

You all started to put down roots, as they say.

Exactly. You start having what I call “the dual life.” There’s a version of you that still exists back where you are from, but also the version of you that exists here. That duality that coexists is the bardo. You are no longer fully here, neither there. I spent a lot of time with that uncertainty, that indecision. There were good reasons to stay, but also to go back. No matter what decision you make, you’ll always think about what wasn’t but could’ve been.

When did this crisis of national or cultural identity begin for you, or has it been there ever since you migrated?

The first two or three years living here I fell into depression. We arrived in 2001 a week before 9/11. This country transformed. I remember I would walk down the street near my house and there were American flags everywhere. If I threw a piece of trash in a trash can on the street, people would observe me and question if what I had put in there was a bomb, because of my brown skin. There was so much suspicion. The neighborhood watch people would stop me on my street to question me, “What are you doing here?” “I live here!” “Show me your license.” Cabrón. Profiling. Those first years were tough.

The Oscar winning director’s three-hour Netflix film, ‘Bardo,’ has divided audiences and met with sharp criticism at the Venice and Telluride film festivals.

There’s a scene in “Bardo” when Silverio has an exchange with his son, and he refers to himself and the family as “first-class immigrants.” Why did you decide to acknowledge this privilege or distinction between you and other Mexicans here?

The phenomenon of migration doesn’t only include those who have experienced economic hardship. We are so many millions that there are many stories. And each story of every immigrant is valid regardless of the circumstances of each person. But there’s also an abyss between my situation as someone who has worked, who has a privileged economic position, who can come and go between countries, compared to someone that doesn’t have these opportunities. I wanted to make sure that was clear.

When I made “Carne y Arena” I interviewed over 500 migrants and worked with them for over a year and a half. Their stories broke my heart. Despite the enormous differences that existed between their reality and mine, their honesty and how they opened their hearts to me gave me the courage and the need to be honest myself and open my own heart and tell my story, even as privileged as I am. But I always knew it was important to acknowledge that I’m a privileged person. Still, the immigrant conscience is the same. Those migrants and I share the emptiness, the melancholy, the nostalgia, the bardo. That’s shared with everyone, with those who are DACA, those who have a green card, we all feel that absence.

Why do you think we become more patriotic once we leave our homeland?

Because of an accumulation of absences. Those absences are like a memory of someone. Like if a friend dies, you won’t allow anybody to speak ill of your friend who’s passed. The same thing happens when your country is absent from your life, you defend it. But the moment you go back to Mexico you start criticizing it [laughs], but when you are outside the country, Mexico becomes like an untouchable memory of someone who is deceased.

At some point Silverio explains, “I can’t understand my country, I can only love it.” That stuck with me as a rather honest way of describing his relationship to Mexico.

When you think you have finally understood Mexico, it surprises you again. There’s no way to understand its contradictions and its mysteries. It’s something strange, Mexico, where cumbia and death coexist. There’s something bloody, violent, viscerally dark about Mexico, but also light, joy, and color that is so contrasting, cabrón [sighs]. It’s so imposing. We are sort of like the axolotls, a sort of larva or salamander, both of sea and land, which is transformative. If you cut off a limb it grows back. We are not Spaniards, but many don’t want to be Indigenous or maybe we want to be Indigenous and want to cut all ties to Spain. But that in-between state is inescapable because we haven’t yet defined who we are. The idea of mestizaje is another profound wound that defines us.

Late in “Bardo,” there’s also a confrontation between Silverio and a homeland security agent who refutes his desire to call the U.S. home. Was this scene inspired by any personal experiences or anecdotal information from other people?

That scene happened to my wife exactly as you saw it. Line by line, just three years ago. She arrived crying, and I asked her what had happened, and she told me the story and it stayed with me. But we’ve had tons of similar stories. In 2003 while filming in Memphis, I had a reckless driving incident, and that stayed on my record. I had an O-1 visa, which you have to renew every six months, so for the next 15 years every time I came back to the U.S. they would send me to secondary [screening]. Even in 2018, this would still happen because of something from 2003. I would get questioned. They are always unnecessarily rude, unwelcoming. Your life depends on a f— piece of paper and the agent you get when you enter.

Have you ever considered becoming a U.S. citizen?

No, because living in the bardo entails not having certainty. And I still don’t know if I’m going to stay here forever or not. I thought, “Why would I go through the whole process if maybe one day I decide I don’t want that and I’ll get in trouble?” Twenty-one years later, my wife and I continue to discuss where are we from and where are we going, cabrón. We’re just passing through. I now embrace that uncertainty. It gives a certain freedom of becoming something else. That perennial state of transformation doesn’t worry me anymore.

We surveyed The Times TV team to come up with a list of the 75 best TV shows you can watch on Netflix. As in, tonight.

Now that you have lived here for 21 years, how do you define home?

I’ve understood that my only true nation is my family. That’s the only place where I don’t need a passport. That’s where I can feel home. Everything is political and geographical.

Do your children consider themselves Mexican American? Or how do they think of themselves, being born in Mexico but raised here?

That’s a difficult question. My daughter Maria, I think she feels closer to Mexico. And my son, now he’s more attached to American culture, but we speak Spanish with each other. When my daughter was born, I started filming a home movie for her. My goal was to give it to her when she turned 20. I filmed the first day of her life in the hospital room. I filmed her uncles and aunts, our friends, and I would ask them to send her a message on camera. More than 20 years went by, and I forgot to give her the film. I gave it to her three years later, and we watched it together. She was very excited. She saw my face as a young man full of illusion, a first-time dad.

I told my sister-in-law that I had given Maria the film, and she asked her, “What did you feel watching it?” And my daughter started crying unconsolably and she told me, “That film is all that never was.” It broke me. “Bardo” is made precisely from all that never was, the stories that never happened because we left. They are slices of feelings that once existed but were transformed. It’s a movie about voids, what we lose. When you asked me if I would ever go back, it doesn’t matter what I do now, everything will have a parallel possibility, a duality in our existence because we left. We are trees that were transplanted into another soil, but some of the roots stayed over there. That duality is the bardo.

At this point in your life and career, how do you understand success?

Both success and failure are great imposters. Success can be more dangerous than failure. Failure is a refuge where you go lick your wounds. It teaches you a lot. It makes you wiser. Success can be more misleading and intoxicating. When you succeed there isn’t necessarily any growth, but maybe even quite the opposite. We have been convinced that success is a real place where an external goal will solve your insecurities, your fears. But when you attain it, you realize this external goal won’t solve anything. It’s only temporary. I’ve learned not to take success seriously. It’s nice and I’m thankful for it. It’s definitely more pleasing than failure evidently, and you prefer it, but I no longer need to race towards success.

I knew making this movie entailed a great risk. I’m very proud of myself for having the courage to be disliked. That for me is success right now: having the strength to know that I can be misunderstood, that people can assume what they want from the film and that I can’t control that. I didn’t have that bravery before. That’s something I want to pass on to young Latinos, to have the courage not to please people. That narrative of trying for everyone to like you is very dangerous because it turns art into a cowardice act to appease and to please everyone. Stories become homogenous in order to maintain everyone’s acceptance and so no one gets upset. No praise is going to make your film better, and no insult makes it worse. Do what you have to do, say what you have to say.

Sometimes people may feel like they have to downplay who they are in order to fit in here.

When we first moved here, my son was 4 years old, and I enrolled him in a kindergarten. And that was very traumatic for him. The Anglo teacher had a young assistant from Guatemala. I asked her, “Could you please translate for my son so he can slowly navigate school?” And she said yes. But then I would pick up my son from school and his lunch was intact. He would pee on himself, and he stopped being the joyful child he was before. A few days later I discovered that the assistant wasn’t translating for him. When I asked her why, she told me, “I don’t want to speak Spanish because I don’t want the kids to think I’m a housekeeper. I came here to be a teacher.” I was angry, but then I understood that she was terrified of what the kids would think of her if she spoke Spanish. She hindered her identity to be perceived as American. It caused me so much sorrow, for my son, but also for her. That was more than 20 years ago, I hope that young people today can be proud of who they are and that they don’t feel like they need to become something they are not. Embrace what this country has given you, but don’t suppress who you are.

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.