Can ‘1917’ follow the path of another one-shot movie, ‘Birdman,’ to Oscars glory?

The one-shot movie is to cinema roughly what the triple axel or quadruple jump is to figure skating: It carries a high degree of difficulty, but if you manage to nail it, you’re sure to wow the crowd. Plenty of films have featured long, dazzlingly complicated shots — think “Goodfellas,” “The Player” and “Children of Men,” to name just three famous examples — but relatively few have ever attempted to sustain that feat over two whole hours.

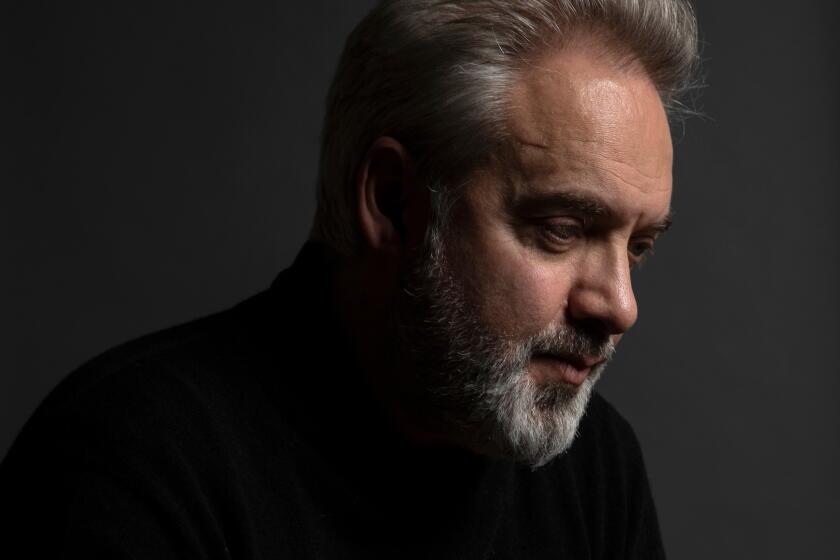

That dizzying cinematic high-wire act is precisely what director Sam Mendes set out to achieve with his World War I epic “1917,” which has grossed $250 million worldwide since its release in late December. “The feeling when you’re on the brink of shooting is like taking a deep breath and then going down the ski slope,” Mendes told The Times in November. “There were moments I just thought, ‘Oh, God, why am I doing this to myself?’”

For Mendes, in making the movie as if it were filmed in a single, unbroken shot, the goal was not simply to show off his technical wizardry, but to fully immerse the audience in the story of two British soldiers on a perilous mission behind enemy lines. “I didn’t want it to feel ostentatious or gimmicky,” he said. At the same time, there was an undeniable secondary upside to the one-shot gambit: If it worked, Oscar voters would almost certainly sit up and take notice.

In that respect, mission accomplished. “1917” earned 10 Academy Award nominations last month, tied with Quentin Tarantino’s 1960s fantasia “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood” and Martin Scorsese’s gangster epic “The Irishman” and just one nod behind the field-leading dark comic book smash “Joker.” Now, following wins at the Golden Globes, the Producers Guild and the BAFTAs, the film is considered an odds-on favorite to claim this year’s best picture prize on Sunday.

There’s just one catch, though: Only four films in the past half-century have claimed the best picture award without also scoring a film editing nomination — yet a one-shot movie, by its very nature, would seem to require very little in the way of editing. And indeed, “1917” failed to land a nod for its editor, Lee Smith.

The Academy Awards are fast approaching and Oscar pools are being organized. Let our film critics Kenneth Turan and Justin Chang help you analyze the major categories with their predictions.

Should “1917” manage to go the distance, it would follow the flight path of Alejandro Iñárritu’s 2014 black comedy “Birdman,” which parlayed a similar one-shot gambit — in that case, following a fading Hollywood star as he struggled to mount a Broadway production — to four Oscars, including best picture as well as director and cinematography.

In winning best picture, “Birdman” became the first movie to do so without a film editing nomination since 1980’s “Ordinary People.” (“Annie Hall” and, curiously, “The Godfather Part II” were the only other two movies to manage that in the past 50 years.)

In reality, neither “1917” nor “Birdman” was actually shot in a single continuous take. Both Mendes and Iñárritu carefully staged long sequences with their casts and crews — anywhere from a few minutes up to one 15-minute shot in “Birdman” — then stitched those sequences together in such a way as to make the seams disappear. Accomplishing that required not simply expert camerawork but some deft, if largely invisible editing.

In the case of “Birdman,” a snub in the Oscars editing category was perhaps understandable. Promoting the movie, Iñárritu spoke extensively about the meticulous preparation in rehearsing his actors for extended takes and the challenges in choreographing the scenes with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki. But there wasn’t that much discussion about the work that his longtime editors, Stephen Mirrione and Douglas Crise, did in melding the tracking shots.

“The whole process was terrifying, and it made me wonder if I had been relying too much on editing before this,” Iñárritu told The Times in a 2014 interview. “It was thrilling not having a safety net.”

Knowing how closely tied the film editing and best picture categories have been in the 92-year history of the Academy Awards, though, the awards consultants working on “1917” wanted to make sure its editor, Oscar-winner Smith (“Dunkirk”), was a prominent part of the film’s promotional campaign.

Speaking to The Times weeks before the Christmas release of “1917,” Mendes highlighted Smith’s key role in making the film. “We had to observe moment to moment what the movie needed at every point, and in that process, Lee was a pivotal figure,” Mendes said. “He was stitching the movie together and adding sound and temp score and feeding it back to me incredibly quickly so I could judge what the rhythm of the next scene could be and whether we were getting away with it.”

Smith, however, was at home in his native Australia, when “1917” had its first unveiling at New York Comic-Con in early October. Not surprisingly, media coverage honed in on the precise collaboration between Mendes and acclaimed cinematographer Roger Deakins, who earned his 15th Oscar nomination for his work on the film.

Smith did participate in several awards season events with the production team in December, including a screening for academy members where he spoke of the “pure terror” of looking at the daily footage and building the film during the shoot.

But voters in the academy’s editing group aren’t any different from their counterparts in other branches. Recognition for “best” tends to go to films and performances with the “most.” And it’s difficult for a film constructed to appear as if it’s one unbroken shot to get much traction.

Director Sam Mendes on the struggle to pull off his WWI epic, ‘1917’: from persuading Hollywood to make it to using technology to achieve a visual feat.

(Perhaps the most famous one-shot film prior to “Birdman,” Alfred Hitchcock’s 1948 crime thriller “Rope,” failed to score any Oscar nominations. In an interview with Time magazine while promoting “Birdman,” Iñárritu dismissed comparisons between his movie and Hitchcock’s, calling “Rope” “a terrible film.”)

While it failed to land an Oscar nod for editing, “1917,” like “Birdman,” did score a nomination in the original screenplay category for Mendes and co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns. While that may seem surprising given the relative dearth of dialogue in the movie, Wilson-Cairns notes that the film’s one-shot approach posed major screenwriting challenges.

“You end up throwing almost everything you know out the window,” Wilson-Cairns told The Times recently. “You can’t use exposition the way you traditionally do because it sticks out like a sore thumb. You can’t cut through time. You’re absolutely rooted in these characters and what they see. So you have to think about how the story is going to breathe in a different way and how you’re going to tell the story visually with so little dialogue. That requires a lot of elbow grease.”

While its one-shot approach has unquestionably helped vault “1917” to awards glory, given the unpredictable twists of this year’s compressed awards season — and with Bong Joon Ho’s “Parasite” emerging as a potential best picture darkhorse — it remains to be seen how the film will fare at Sunday’s Oscars. But speaking to The Times in November, Mendes, who won the best picture and director prizes 20 years ago for 1999’s “American Beauty,” said he was just trying to tune all the awards noise out.

“You have to keep yourself selectively blind and just put your head down,” he said. “I love that people are talking about that stuff because it means that more people are going to go see the movie. And lest we forget, that is the point of these things: to make people go and see the movies. There’s no point in fighting it. As long as you remember that and the fact that the Oscars are, in fact, a TV show, then you’re fine.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.