It’s the twilight of the Jonathans, and Jonathan Lethem feels fine

On the Shelf

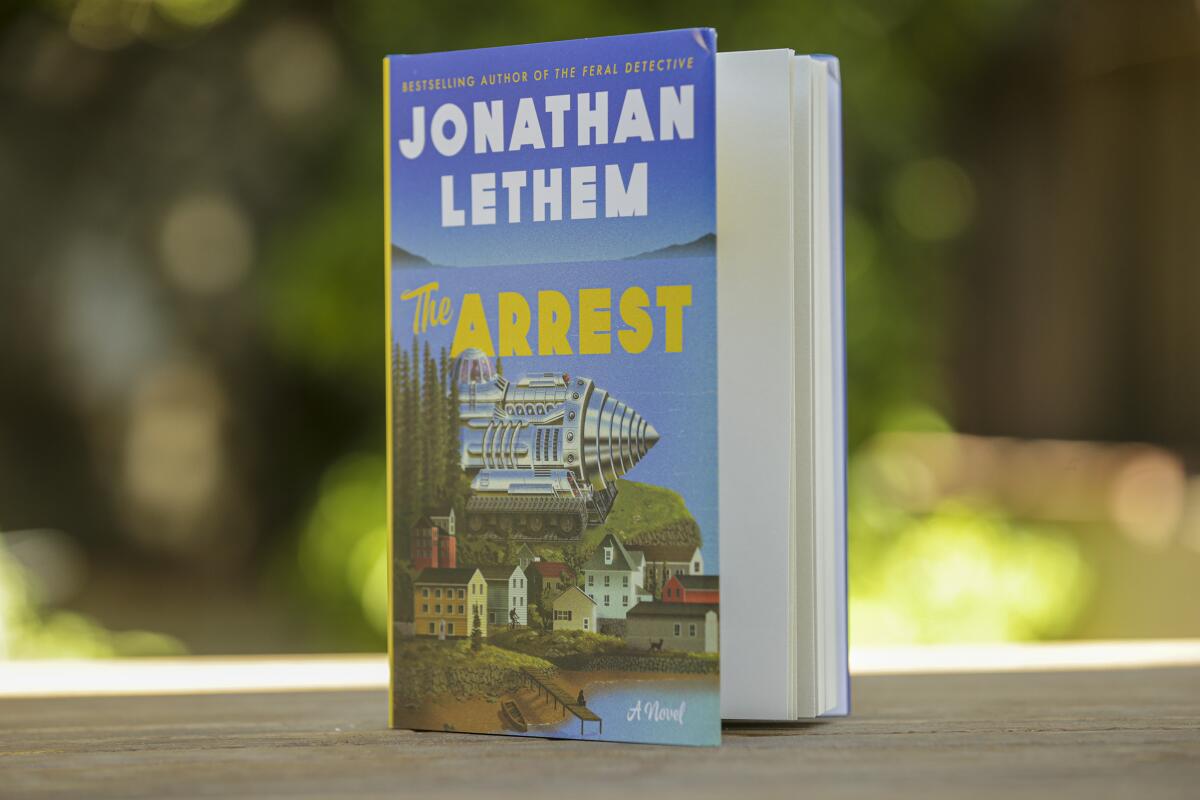

The Arrest

By Jonathan Lethem

Ecco: 320 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The Jonathans! Suddenly it seems like a long time ago. They arrived between 1995 and 2005, novelists tasked with relieving the graying Roth and Updike as our frontline reporters from the psyche of the American male. It was a job we were sure would last forever.

It helped but was not essential to be named Jonathan. Joshua Ferris and Jeffrey Eugenides and Junot Diaz — all Jonathans, and maybe even Jennifer Egan too. And that just puts us clear of the letter J.

It was a classification at once mindless and perceptive. As the Jonathans sailed to black-tie literary fame, a different world was quietly cracking open behind them, in which the roads to mainstream success as a novelist were not mapped primarily through affluent, melancholy whiteness. Even if you liked some or all of the writers individually, the nickname had a nicely fed-up feel. It was a coincidence that so many of the best rising novelists were called Jonathan; simultaneously, it was no coincidence at all.

“It was just funny,” Jonathan Lethem said recently. “After so many efforts not to be pigeonholed or categorized, it was a perfect form of humbling.”

He paused, perhaps reconsidering how funny it really was, and added, “It was the very stupidest identification you could ever have.”

Lethem, 56 now and the author of a new novel, “The Arrest,” was and to some extent remains the Jonathan most closely identified with the most Jonathan of places, Brooklyn. His pacy, cerebral private-eye novel “Motherless Brooklyn” brought him wide notice and its 2003 followup, “The Fortress of Solitude,” a decades-spanning comic book Brooklyn fantasia, briefly made him one of the most ubiquitous novelists in America.

Emily St. John Mandel’s last novel, “Station Eleven,” envisioned a pandemic. “The Glass Hotel” plumbs financial doom.

Both are distinctively novels of the city, and readers may have been given the mistaken impression that it was Lethem’s only subject. But he has always been a wide-ranging writer. An editor whose opinion I regard highly told me she most admires “Amnesia Moon” and “Girl in Landscape,” the two books that directly preceded the author’s most famous ones. They are both post-apocalyptic novels, early contemporary inspirations for that indomitable trend.

They are also thus forebears of “The Arrest,” another of Lethem’s post-apocalyptic earth operas, as I started to think of them (more or less a space opera without space). In Lethem’s words, the novel is about “this incredibly soft collapse, where organic farmers run the world.” Its protagonist, Journeyman, is fortunate enough to have a sister who’s one of those farmers, and they’re living peaceably in the afterworld until Journeyman’s old, skeevy Hollywood running buddy Peter Todbaum appears in a monstrous armored vehicle, looking to settle scores.

Since 2011, Lethem has been the Roy E. Disney Professor in Creative Writing at Pomona College, a position everyone I spoke to, including Lethem, was at pains to point out had previously been occupied by David Foster Wallace. (Wallace, typically, was always near the Jonathans without seeming exactly like one of them.) He has children — they are in a hardcore Beatles phase — and mortgages on either coast, including one in Maine, not far from the setting of “The Arrest.” One question implicit in the new novel is how many people will get to lead this burgher’s life before it’s taken away.

—-

It isn’t mysterious why stability might appeal to Lethem. He grew up in Brooklyn, the son of a modernist painter (his father) and a passionate activist (his mother), a red diaper baby, the turbulence of politics traced into his earliest memories. Like so many artists of his generation, in adolescence he found a post-hippie sanctuary in the bedroom, specifically in what might once have been deemed nerd culture but is now just culture, reading scads of genre fiction and comic books. He has written about seeing “Star Wars” more than 20 times in a theater when he was 13.

After a spell at Bennington, Lethem spent much of his 20s working at bookstores across Berkeley, which per maps made available to The Times is literally all the way across the country from Brooklyn. At the same time his stylish, exciting, inventive fiction was good enough that it drew the attention of other writers on the West Coast.

His wife told Claremont police that the novelist and humorist who wrote ‘Infinite Jest’ hanged himself Friday night. He was 46.

“He was publishing short stories in the science fiction magazines, and they were good,” recalled Kim Stanley Robinson, who met Lethem at Ursula Le Guin’s house in Napa Valley. Robinson is now regarded in many circles as America’s foremost living science fiction novelist. Karen Joy Fowler, another novelist who has successfully toggled between sci-fi and literary fiction, was also impressed. “He was really steeped in mystery novels, ‘40’s pulp fiction, while also being an intensely literary guy. He was a very gracious person.”

Lethem expected to be the kind of paperback writer who’d be discovered late, if at all; instead, his first few novels made him, in Robinson’s description, a “star.” He moved back to Brooklyn just as the borough surged into consciousness as an artistic frontierland, and in short order became one of its most famous inhabitants.

—-

“There was some New York [crap],” Lethem says.

In conversation Lethem is nervily entertaining, exceptionally bright. He speaks in the practiced sentences of a professor, i.e., in thoughts to which much thought has been given, but long ago. Trying to shake him out of that register is difficult.

When he talks about Brooklyn, however, he sounds less assured, a bit like someone who inadvertently timed the tech bubble exactly right, staggering out of the market much richer but slightly bewildered. There’s a serious randomness governing which writers become famous, and famous writers often sound conflicted about that, disavowing or disputing some of the details of their breakthrough without (understandably) being willing to relinquish the basic validity of it having happened.

Lethem has one of the most elegant responses to this conundrum that I have heard: “The eccentricities of my project ultimately prevailed,” he says, “over the idea that I was supposed to be … whatever it would be … serially failing at the great American novel, which is the only thing you can do with it.”

In fact he does seem to have tried that for a while, producing doorstop novels like “Chronic City” and “Dissident Gardens.” But recently he has reverted toward more conspicuous genre pieces: his previous novel “The Feral Detective” reads like acid-soaked Ross Thomas, and “The Arrest” candidly rests on long, intricate lines of descent through fantasy and sci-fi.

It’s a wonderful read, the writing gracefully gonzo, the emotional beats often unexpected yet quite right. Lethem doesn’t possess every novelistic gift equally (“I gave up on him when he named a character Perkus Tooth,” the critic John Self said, and it’s true that un-cartoonish characters are not his strength). But his work has become genuinely affecting, in a way it wasn’t earlier in his career, since at least the underrated “Dissident Gardens.”

Robinson, for his part, views “The Arrest” as an important change in Lethem’s vision. “I am always reading him as a political thinker,” Robinson said. He thinks Lethem’s early education in activism left him strongly skeptical of the power of direct action to effect change, a stance that may be softening slightly. “The Arrest,” Robinson suggests, offers a glimmer of good cheer about the possibilities of a social contract even in a fallen world.

Lethem himself sees complicity as perhaps the major theme of his novels. (Writers are notoriously uneven critics of their own work.) In truth it seems like something more banal and admirable: strangeness, the strangeness of our world and other possible worlds, and the places where those surrealities merge.

Celebrated for her novels, occasionally vilified for a persona she can’t control, the author of “Death in Her Hands” is our prophet of loneliness.

In this sense Lethem’s fluorescence in Brooklyn was only the most zeitgeisty moment the author has had in a long career dedicated to writing intelligible but pointedly odd novels. Considering this subject, Lethem said he often thought about the liner notes Neil Young wrote for the collection “Decade.” “He gets to ‘Heart of Gold’ and says, this song brought me to the middle of the road. And I realized I wanted to be in the ditch instead.”

Well! That is something easiest to decide from the middle of the road. But they were always earnest, fantastical souls, the Jonathans, in helpless love with the touchstones of their youth, “Gunsmoke,” the Fantastic Four, Neil Young, almost anything televised or printed really, their prose a blizzard of references and have-you-reads. In a way they belonged to the last backwater: Brooklyn just before the totalizing diaspora of the internet, the last place in America that could plausibly believe it was the center of the artistic universe and that the stories of a group of white men were the best way to understand ourselves. “The Arrest,” perhaps not coincidentally, recreates the disruption of a similarly charmed, problematic community.

It’s not surprising that it’s such a smart, funny book, because the Jonathans produced a huge number of smart, funny books, and even — in “The Corrections” and “Freedom,” both by Jonathan Franzen — two masterpieces of the novel. But as gifted as they were, Lethem and his peers very clearly also benefited from structural factors of geography and misogyny.

The cost of this is that they have been on the losing side of that ledger since — the curious and intriguing progression of Lethem’s work overlooked by some readers because of his first name.

Even the construction of this profile around the concept would no doubt irritate him inordinately. But of course it’s also the reason the profile exists. He accidentally summed that quandary up to me when he was discussing — with winningly sincere modesty — a different subject, the non-radicalism of his decision to mix genres so often. “I just had the luck of coming along when it was an obvious thing to do,” he said. “I was willing my own context into existence.” He hesitated, thinking. “And it sort of half worked.”

Over the last three months, 17 writers provided diaries to the Times of their days in isolation, followed by weeks of protest. This is their story.

Finch’s novels include the Charles Lenox mysteries.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.