How the small screen breathes new life into classic film noir

Screenwriter Scott Frank emerged as a master of snappy banter in the ’90s when he adapted crime novelist Elmore Leonard’s witty stories “Get Shorty” and “Out of Sight.” So it seemed only natural that Frank, after creating Emmy-winning projects “Godless” and “The Queen’s Gambit,” would want to tap film noir’s rich tradition of smart talk when he approached veteran writer-producer Tom Fontana (“Homicide,” “Oz”) with a proposition.

Fontana recalls, “Scott invited me to lunch and literally said: ‘Sam Spade, South of France, 20 years after “The Maltese Falcon.”’ I said, ‘I’m in.’”

And so began the story of “Monsieur Spade.”

Spearheading a mini-renaissance of TV noir inspired by the black-and-white crime thrillers that captivated audiences in the 1940s and ’50s, AMC’s six-episode series stars Clive Owen as Dashiell Hammett’s famous detective, forced out of retirement in 1963 when nuns in a nearby convent are murdered. Apple TV+ has “Sugar,” starring Colin Farrell as a cinephile private eye in contemporary L.A. hired to locate a missing woman. Two more, from Netflix, add to the genre. “Ripley,” which deploys noir-style shadow and light compositions to visualize the misadventures of a murderous con man (Andrew Scott), and Guy Ritchie’s “The Gentlemen,” which lends a British accent to the hard-boiled “dame” archetype in the person of Kaya Scodelario’s deadpan crime boss, Susie Glass.

The stars of Netflix’s “Ripley,” an adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel, talk about why we can’t get enough of con artists, how they’ve been duped and all those stairs in the show.

Each show reflects in its own way the influence of a gritty genre that situated world-weary protagonists in cold, uncaring worlds armed only with their wits, fists, guns and rat-a-tat dialogue.

In the case of “Monsieur Spade,” Fontana says he and Frank, who also directed the series, took pains to craft a terse title character worthy of the canon. “For us, the key to writing the dialogue was understanding Sam’s attitude about the people he was having these exchanges with — when he had to be respectful and when he could be rude. [Sometimes] Spade throws out a smart line and it’s like a defense mechanism: ‘Don’t get too close to me.’”

To avoid any semblance of film noir parody, Fontana says, “Scott made a conscious choice to shoot noir dialogue in the sun, which I think helps it feel fresher. There aren’t all those weird angles and shadows that you find in the noir cinematic playbook. ‘Monsieur Spade’ is shot almost like a French film of the ’60s, but the words are Hammett-like.”

Series star Owen, a longtime fan of noir in general and “Maltese Falcon” star Humphrey Bogart in particular, sparked immediately to the “Monsieur Spade” script. “I remember having a meeting with Scott and saying, ‘Don’t freak out because I’m not going to do a bad impersonation, but I’m really digging into Bogart for this because I think it’s helpful to have him as a template’ and Scott said to me, ‘That’s so weird because when I wrote this, I kind of had to hear Bogart say the lines [in my head] to know I’d nailed it.’”

The actor, who keeps vintage “Maltese Falcon” and “The Big Sleep” posters on the wall of his office, discovered Bogart at London repertory houses in the ’80s while studying at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. “I saw ‘Casablanca,’ and that’s when I went down the Bogart rabbit hole,” says Owen. “Acting kind of changed after Bogart’s era because Brando came along and suddenly we’re watching people who struggle to express themselves. People think of him as being laconic, but Bogart was actually super nimble with his dialogue.”

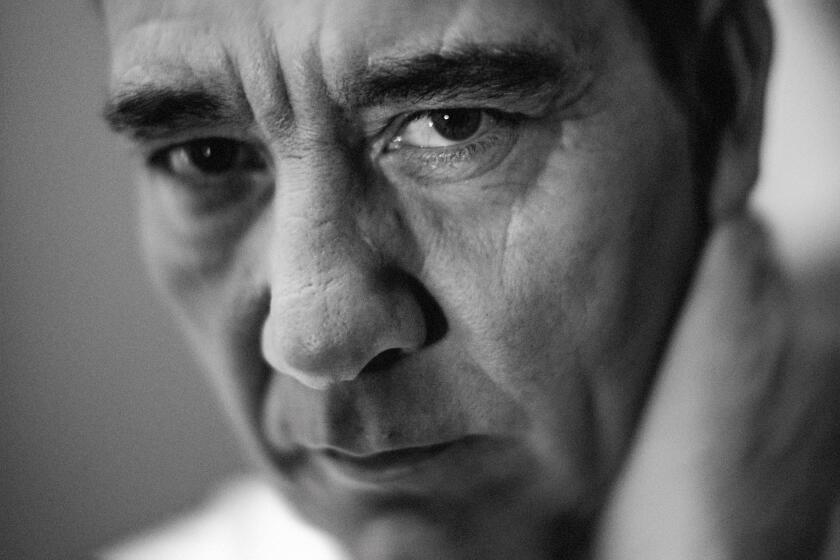

In AMC’s ‘Monsieur Spade,’ the British actor Clive Owen plays detective Sam Spade 20 years after the events of ‘The Maltese Falcon.’ Humphrey Bogart, who played the character in 1941, was inspiration.

Owen admires the sheer velocity with which noir characters delivered their lines. In keeping with that tradition, his Monsieur Spade never hesitates, never pauses, never says “um.”

“Looking back at those films you see these are quick-minded people, and when you can do [the scene] at speed, that’s when the intelligence comes through. Noir dialogue has restraint, it has wit, it has economy. I don’t want big long speeches about what I’m feeling and what I’m thinking,” he says. “Noir is expressed through what people are doing. [The heroes] don’t tell you how they feel or think.”

Apple TV+’s “Sugar,” like “Monsieur Spade,” forgoes the shadow world of black-and-white noir to surround private eye John Sugar in the warm light of Southern California. But director Fernando Meirelles, justified by the hero’s passion for old movies, interpolated the narrative with snippets of noir classics like “Kiss Me Deadly” (1955), “The Big Heat” (1953), “Double Indemnity” (1944) and Bogart-starring “Dead Reckoning” (1947).

“We were inspired by many film noirs and characters, but it was Fernando Meirelles and his editor, Fernando Stutz, who experimented with the film clips during the director’s cut,” says “Sugar” producer Audrey Chon. “We were excited to see the intercutting of scenes within the show [as a way] to play with time and place.”

“Sugar,” created by Mark Protosevich, uses a signature noir device, the deadpan voice-over, to help define its protagonist as a soft-boiled detective who subverts the tough-guy persona by giving a homeless man $100 bills and taking in a stray dog who looks right at home in the passenger seat of Sugar’s vintage Corvette. Chon notes, “There’s an impenetrability with traditional hard-boiled detectives that make them inaccessible. We loved this idea of a detective with sensitivity and wounds that he isn’t hiding. Sugar talks about his feelings and fears openly. It feels very real and modern.”

While Hollywood’s film noir golden age peaked in a postwar America that welcomed cynical detectives and wise-guy crooks, today’s hard-boiled crime stories continue to find an audience. Owen thinks he knows why. “People assume noir is full of immoral characters, but I think, in good noir, the lead character is trying to do the right thing in a bleak, tough world. When people have a decent moral compass, we like those characters.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.