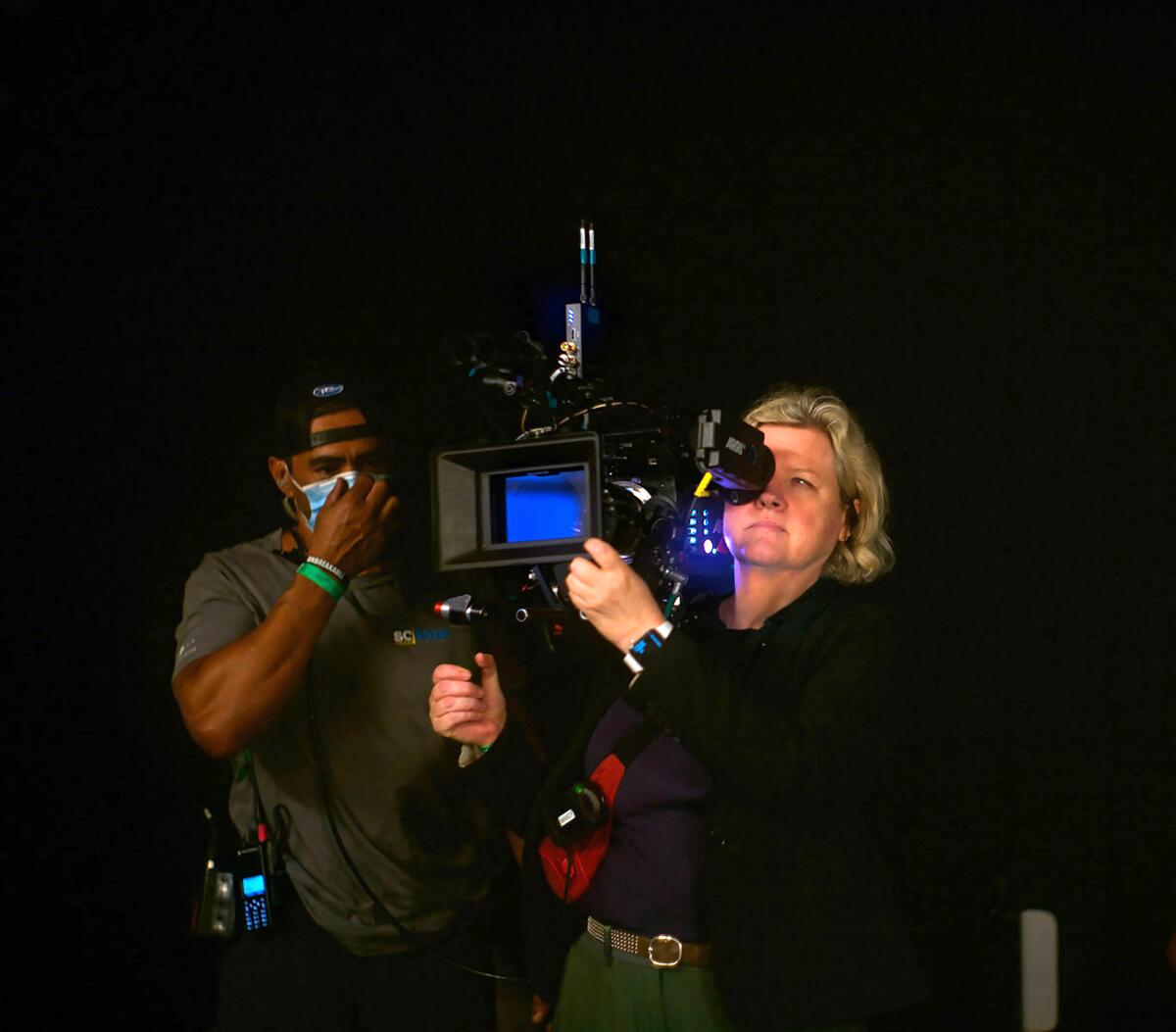

Cinematographer Mandy Walker helps find the nuance in the flash and dazzle of ‘Elvis’

- Share via

A spirited effervescence hums in Mandy Walker’s voice. The Australian cinematographer received her first Oscar nomination for her dazzling “Elvis” imagery, and she shares over the phone that collaborating with director Baz Luhrmann has been a “highlight of her life” and that being recognized this way is “the icing on the cake.” “It was like we were doing a dance the whole time,” Walker says of the dramatic biopic, a story that paints the life and music career of Elvis Presley (Austin Butler) as told by his insufferable manager, Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks).

The visual majesty is the result of intense research and shots were crafted to introduce each period of the Elvis journey through subtle shifts in color, lighting and even lens choice. Photographers Gordon Parks and Saul Leiter provided inspiration for color and tone during Elvis’ early years. Softer lighting cues, rich contrast and deep black levels illuminate the 1950s, and saturated colors embellish the ‘60s. Spherical lenses (Sphero 65’s) framed his childhood and into the ‘60s for their blemish-free qualities, whereas a 65-millimeter large-format camera (ARRI Alexa 65) captured the growing icon in an epic scale. The biggest leap in look comes during the 1970s when Elvis lands in Las Vegas. Here, Walker changed to anamorphic (T Series) lenses.

The onetime Disney actor knew he had to wait for the right project. And when ‘Elvis’ came along, he was ready to go all in.

“I felt that represented a time with the audience where things were switching in a bigger way,” she says. In photographing the era, Walker asked lens specialist Dan Sasaki at Panavision to adjust the lenses to what they would have looked like in the ‘70s. “A lot of modern anamorphic lenses have that blue flare that feels a bit sci-fi, so I got him to put green, magenta and orange back into those horizontal flares.” The boost in color complemented the change in color palette that showcased rich mid-tones and pastels in the costumes and production design of Sin City. “The thing for me was to be very cognizant moving between periods,” notes Walker. “The transition from one period to another was something Baz and I sat down and mapped out. We didn’t want it to look like a different movie.”

Walker also laced nuanced motifs throughout the film. “What we are representing is Elvis’ impact on American music and culture but also what happens in society at the time and how that influenced and impacted him,” Walker says. One such sequence shows a young Elvis peeking through a hole of a juke joint as Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup (Gary Clark Jr.) bellows the song “That’s All Right” as a couple passionately dance on the wooden floor.

“I wanted that to feel like it was the first time Elvis was seeing a concert and how special it was for him,” she says. “I had these shards of light replicating little spotlights to create this little moment that echoes what’s going to happen in the future and how it feels for him.” Musical performances, however, were reproduced as close as possible using reference material and vintage footage. Photographs by Alfred Wertheimer guided the 1956 Russwood Park charity performance, Elvis’ 1968 “Comeback Special” was fastidiously mapped out, and Denis Sanders’ 1970 documentary “Elvis: That’s the Way It Is” brought to life the International Hotel show in Las Vegas.

For the ’68 “Comeback Special,” where Elvis sings a number of songs including a poetic performance following the assassination of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy, Walker says she meticulously replicated existing footage while adding cinematic flavor to the shots. “I studied the camera angles, the lighting, when they’d zoom in or out, to match exactly what they did. We did the same for the Russwood and International Hotel concerts.”

Filmmaker Baz Luhrmann discusses Elvis Presley’s controversial ties to Black music and what the singer’s dynamic with Colonel Tom Parker reveals about America.

Since the ceiling of the television studio would be visible, the cinematographer found period fixtures and used them as practical lighting, and with some, integrated LED lights into the housing to “smooth out the shadows and make a softer light on Elvis’ face.” To mark exact shots, or what Luhrmann called “trainspotting,” the cinematographer went as far as hiding a camera inside the housing of an old TV camera to get the right angle. A black and white monitor was built into it to re-create the vintage look.

Similarly, for the International Hotel show, Walker blended LEDs in with the period fixtures to complement the lighting. Elvis footage from the original show was later mixed in with the final edit. “I think the biggest challenge for me was the trainspotting material, because the audience and the fans know the footage. The timing of everything had to be perfect,” she says.

Compositionally, Walker says, the language of the camera was based on the emotion and musical performance. The camera team all had to be on stage to learn the songs and choreography that Butler was to perform. Not only to know where the actor was going to be but also so Butler knew where the camera would be going. “We’d fly when Elvis flies, and when the drama is heavy and poignant, we slow down and become very observational,” says Walker. “It was a dance between the camera and him.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.