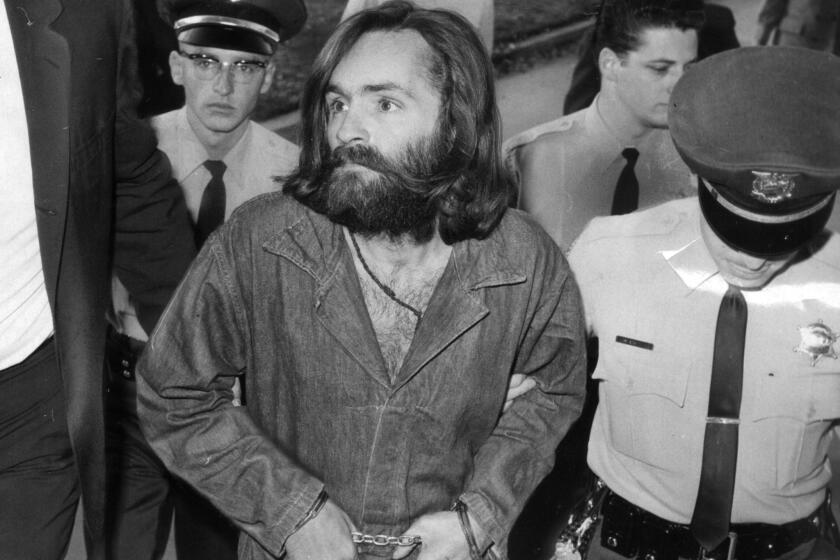

The Manson murders were monstrous. But do the aging killers still belong in prison?

- Share via

For more than 50 years, relatives of Sharon Tate and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca vehemently pleaded with California governors and the state’s parole board: Never free any member of Charles Manson’s so-called family.

“If you have a monster and you are fortunate enough to have caught it, and it was condemned to die, why let it go?” said Tate’s sister, Debra Tate. “I’ve worked with Republican governors and Democrat governors, and every one has always said: ‘We’ll never let them out.’”

That changed Tuesday, when after having repeatedly been denied parole, Leslie Van Houten was released from prison for her role in the notorious 1969 murders in Los Angeles.

While Tate and other family members of the victims decried the release, the move underscores how views of punishment and rehabilitation have changed in the criminal justice system, even when it comes to horrific cases such as the Manson murders.

“The crimes were truly heinous, cruel murders of strangers,” said Hadar Aviram, a professor at UC Law San Francisco and the author of “Yesterday’s Monsters: The Manson Family Cases and the Illusion of Parole,” a book that studies the parole hearings of those convicted. “There’s this idea of: Can this ever be forgiven?”

But, Aviram continued, “I think if you really think about this as a pragmatic, public safety issue, these people don’t pose a risk to public safety.”

Legal experts say an exemplary record during Leslie Van Houten’s 53 years in prison made the legal challenges to her release an uphill fight.

Those familiar with Van Houten’s case point out that the 73-year-old had been deemed a “model inmate” over the years.

“There was no evidence in the record that she continued, after 50-plus years, to pose a danger,” said Heidi Rummel, director of the Post-Conviction Justice Project at USC.

Rummel, who has represented candidates for parole for more than 15 years, said clients have cited Van Houten for their focus on rehabilitation during their time behind bars.

Gov. Gavin Newsom had denied Van Houten’s parole three times, but he was overruled by a California appeals court this year, and announced Friday that he would not challenge her release.

Prisoners’ rights advocates argue that even previously violent offenders who have served lengthy sentences pose a low risk of re-offending compared with their younger counterparts, and say they especially need to be given consideration due to their age and often vulnerable health.

Aviram argues that releasing convicts who have shown rehabilitation — especially those approaching 70 or 80 years of age — poses little risk to society.

According to reports from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, the state has granted parole to about 15% of inmates who have come up for hearings since 2018. About 34% were outright denied.

Before 2008, the state’s parole board approved fewer than 5% of the cases that were reviewed.

The power to reverse the parole board’s decisions has been widely used by state governors, said David Zarmi, a certified appellate specialist lawyer.

“There were very few parole grants that the governor’s office did not challenge on appeal, even under shaky grounds,” he said.

He said that in Van Houten’s case, the governor likely didn’t petition the California Supreme Court because it would risk the court issuing a binding, mandatory opinion.

“The hope is that some of the other appellate panels in the 2nd District, as well as in other districts throughout the state, will have a more sympathetic bent to the governor’s original position in future cases than the California Supreme Court, which has generally more recently been taking a more progressive stance,” he said.

Fifty years later, the Manson “family” murders remain seared into the collective memory of Los Angeles. The question, which persists to this day, is why?

Critics of Van Houten’s release, however, argue that the risk to the public should not be the only factor considered.

Van Houten and another woman held down Rosemary LaBianca as Charles “Tex” Watson stabbed her husband. He handed Van Houten a knife after he was finished, and she testified at trial that she stabbed the woman at least 14 times.

“And I took one of the knives, and Patricia had one — a knife — and we started stabbing and cutting up the lady,” Van Houten testified in 1971. (Patricia Krenwinkel, another Manson follower, was a co-defendant.)

The day before the LaBianca murders, Manson followers — including Watson and Krenwinkel — had killed Sharon Tate along with Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger, Wojciech Frykowski and Steven Parent in a brutal attack at a home on Cielo Drive in Benedict Canyon.

Relatives of the victims called Van Houten’s release this week “nauseating” and “gut-wrenching,” and said they feared it could open the door to other aging Manson family members being released.

Read our full coverage of the Manson murders.

“They are all psychopaths who have manipulated the systems,” said Kay Hinman Martley, whose cousin Gary Hinman was also savagely murdered by Manson followers in July 1969.

Van Houten and others were convicted of murder and sentenced to death, but those penalties were commuted to life in prison due to the 1972 California Supreme Court decision to overturn the death penalty.

For decades, the state’s parole board continued to deny release for any followers of Manson, who died in prison in 2017. That changed in 2008, when the state’s Supreme Court ruled that parole could not be denied purely on the basis of the initial crime.

That change, however, didn’t immediately open the doors for any of Manson’s followers. Records show California governors have repeatedly reversed the parole board’s decisions when they recommended release for Manson’s followers.

“We have four other Manson killers in there, and I fear they will all get out,” Hinman Martley said. “All these killers get all the help they want, but no one is doing anything for the victims.”

The girls of the Manson ‘family’ drove a chill deep into the nation’s psyche that has yet to lift.

Of the Manson family members who were convicted of various crimes in the 1960s, four remain in California state prisons.

Krenwinkel, 75, has been denied parole 10 times. In May 2022, the board recommended she be paroled, but Newsom reversed the decision.

Robert Kenneth Beausoleil, 75, has been denied parole 16 times. He was approved for parole in 2019, but that decision also was reversed by the governor. Beausoleil was denied parole in two subsequent hearings.

Bruce Davis, 80, has been denied parole 24 times during his lengthy stay in prison. The board has granted him parole on seven occasions since 2010 — most recently in January 2021. All of the decisions were reversed by the governor at the time.

Charles Denton “Tex” Watson, 77, has been denied parole 13 times. The board has never approved his release. His next hearing is scheduled for October 2026.

Those decisions, experts say, are both judicial and political.

In Van Houten’s case, the governor strongly opposed her release, said Laurie Levenson, a professor at Loyola Law School. But he realized his efforts to further appeal her parole were unlikely to succeed.

“Politically, this is not something the governor wanted to do,” Levenson said. “But she managed to get out because she managed to become a different person in prison.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.