Charles Manson, mastermind of 1969 murders, dies at 83

An obituary for Charles Manson, dead at 83.

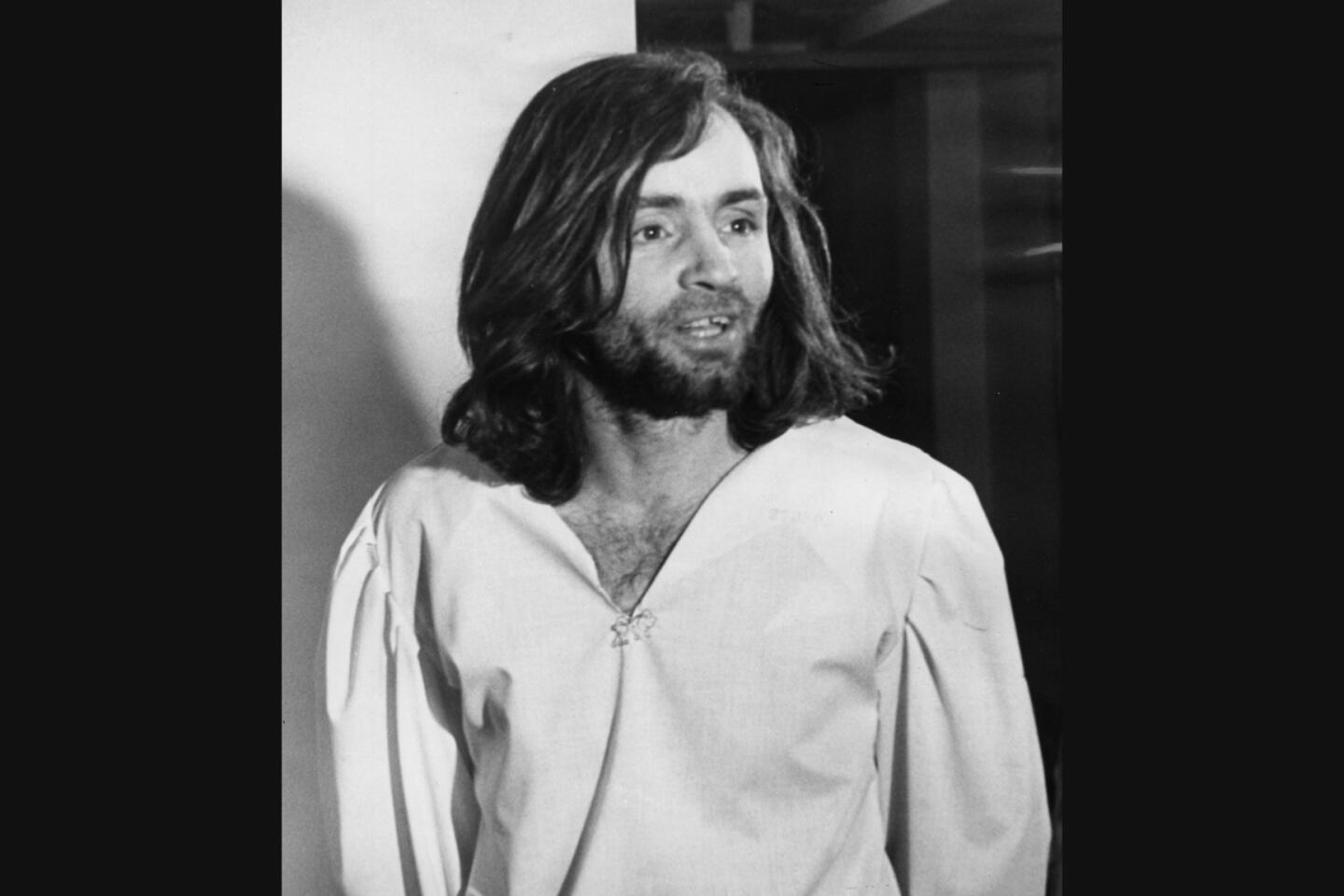

Charles Manson was an unlikely figure to evolve into the personification of evil. A few inches over five feet, he was a petty criminal and small-time hustler. And his followers bore little resemblance to the stereotypical image of hardened killers. Most were in their early twenties, middle-class white kids, hippies and runaways who fell under his charismatic sway.

But in the summer of 1969, Manson masterminded a string of bizarre murders in Los Angeles that both horrified and fascinated the nation and signified to many the symbolic end of the 1960s and the idealism and naiveté the decade represented.

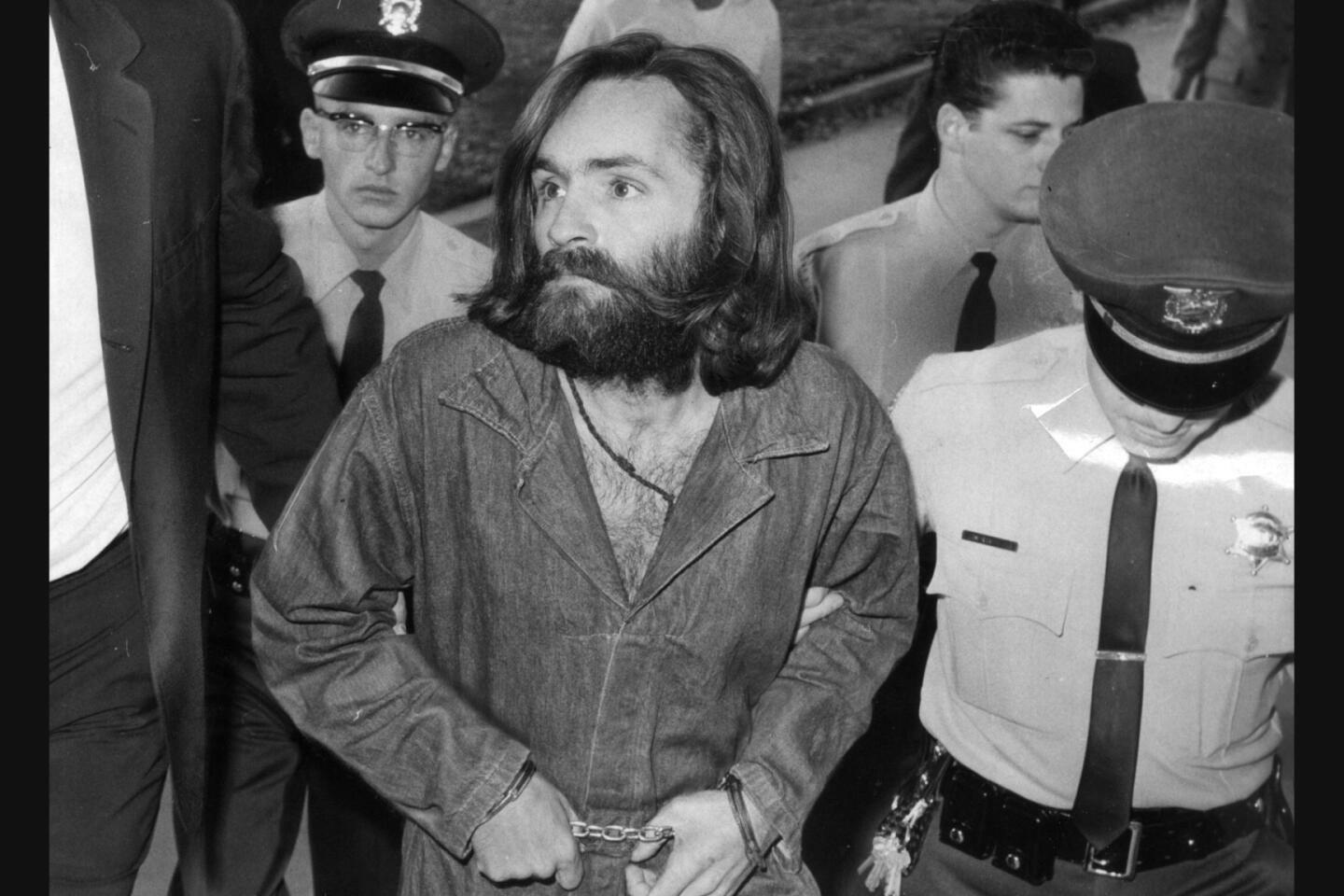

Considered one of the most infamous criminals of the 20th century, Manson died of natural causes at a Kern County Hospital at 8:13 p.m Sunday, according to Vicky Waters, a spokeswoman for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. He was 83.

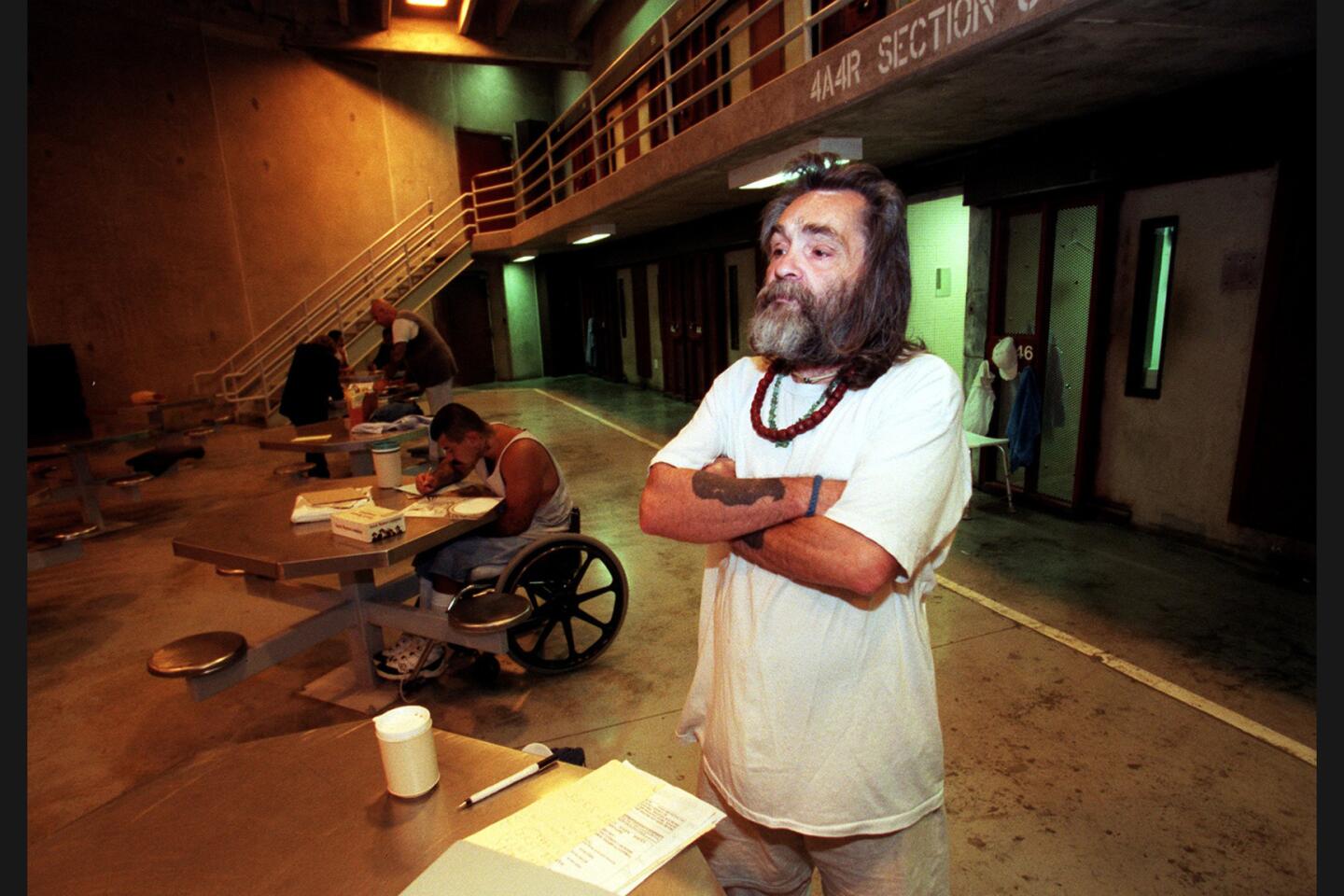

Sentenced to death for the crime, Manson escaped execution when the state Supreme Court declared the death penalty unconstitutional at the time. He spent decades behind bars, an unrepentant and incorrigible inmate who’d been cited for behavioral issues more than 100 times.

Manson did not commit the murders himself; instead he persuaded his group of followers to carry out the killings. The crimes received frenzied news coverage, because so many lurid and sensational elements coalesced at the time — Hollywood celebrity, cult behavior, group sex, drugs and savage murders that concluded with the killers scrawling words with their victims’ blood.

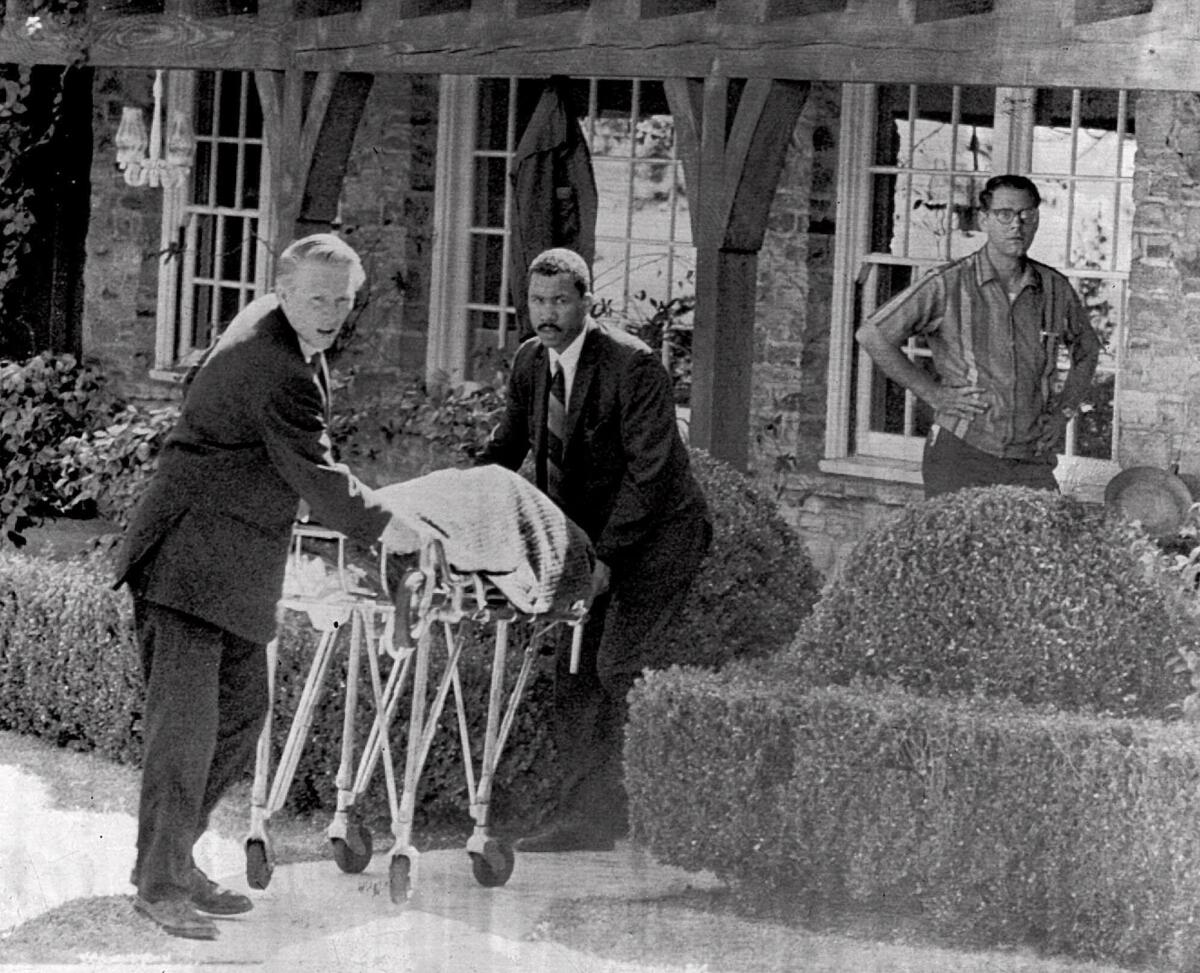

Los Angeles residents were terrified by the crimes. Before the killers were apprehended, gun sales and guard dog purchases skyrocketed and locksmiths had weeks-long waiting lists. Numerous off-duty police officers were hired to guard homes in affluent neighborhoods and security firms tripled in size.

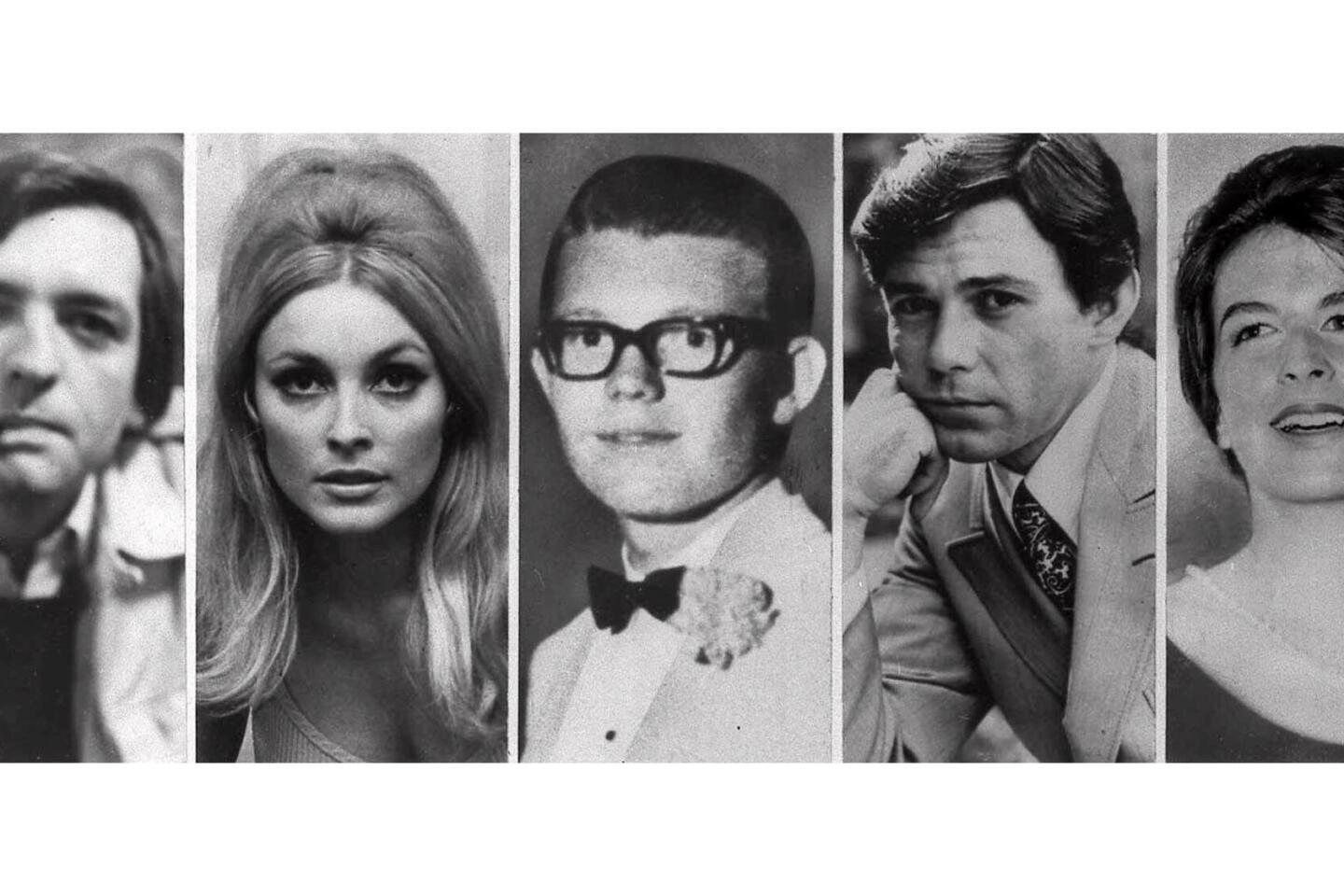

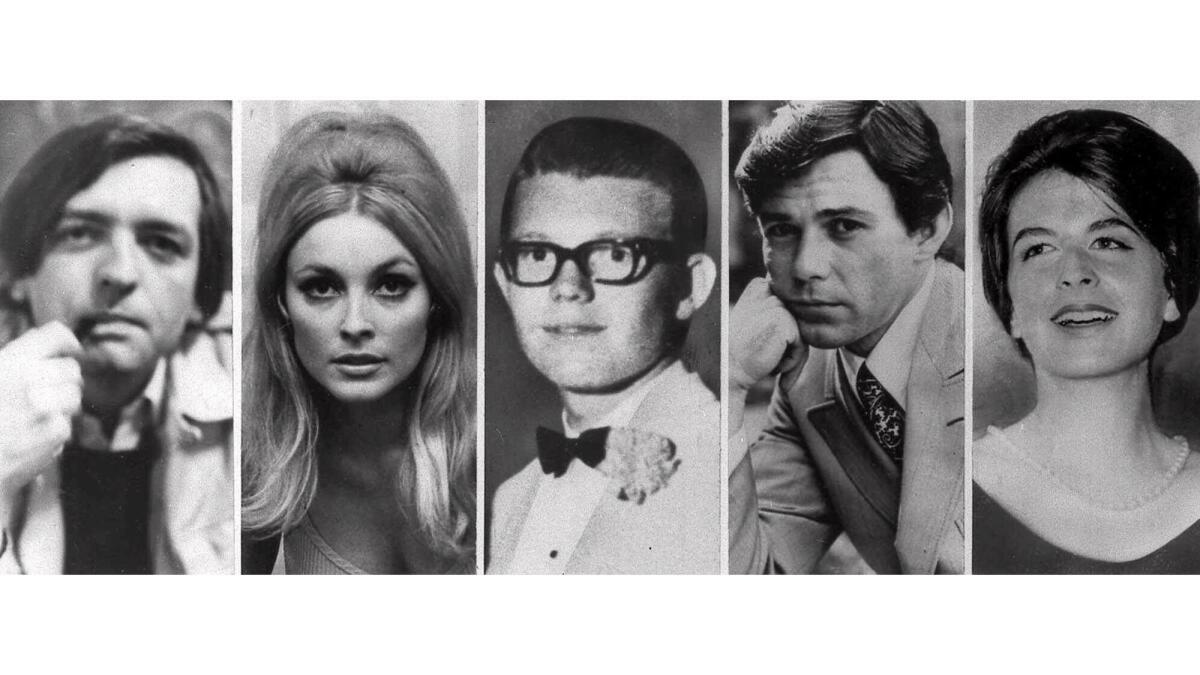

Manson and four of his followers — Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten, Patricia Krenwinkel and Charles “Tex” Watson — were convicted of murdering actress Sharon Tate, the wife of movie director Roman Polanski, in their Bel-Air home on Aug. 9, 1969, along with four others.

Watson had been a high school football star. Krenwinkel a former Sunday school teacher. Van Houten a homecoming princess from Monrovia. And Atkins once sang in her church choir. Linda Kasabian, a pregnant 20-year-old with a baby daughter, who said she was asked to go along that night because she was the only one with a valid driver’s license, testified against the others in return for immunity from prosecution. Atkins died in 2009 in prison; the others remain incarcerated.

Tate, 26, who was eight months pregnant, pleaded with her killers to spare the life of her unborn baby. Atkins replied, “Woman, I have no mercy for you.” Tate was stabbed 16 times. “PIG” was written in her blood on the front door.

The next night they killed Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in their Los Feliz home. Manson picked the house at random, tied up the couple and then left the killings to the others. They cut “WAR” in Leno LaBianca’s flesh and left a carving fork in his stomach and a knife in his throat. Using the LaBiancas’ blood, they scrawled on the wall and refrigerator in blood “DEATH TO PIGS” and “HEALTER SKELTER,” the misspelled title of a Beatles song. Before leaving, they helped themselves to some watermelon in the refrigerator, leaving behind the rinds.

“People were so terrified because these seemed to be murders without a motive,” said lead prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, who died in 2015. “They weren’t robberies or burglaries. It was so random. If you’re not safe in your home, where are you safe? And these murders were particularly brutal. On the two nights there were 169 stab wounds.”

The 9½-month trial — the longest in U.S. history at the time — was as bizarre as the crimes.

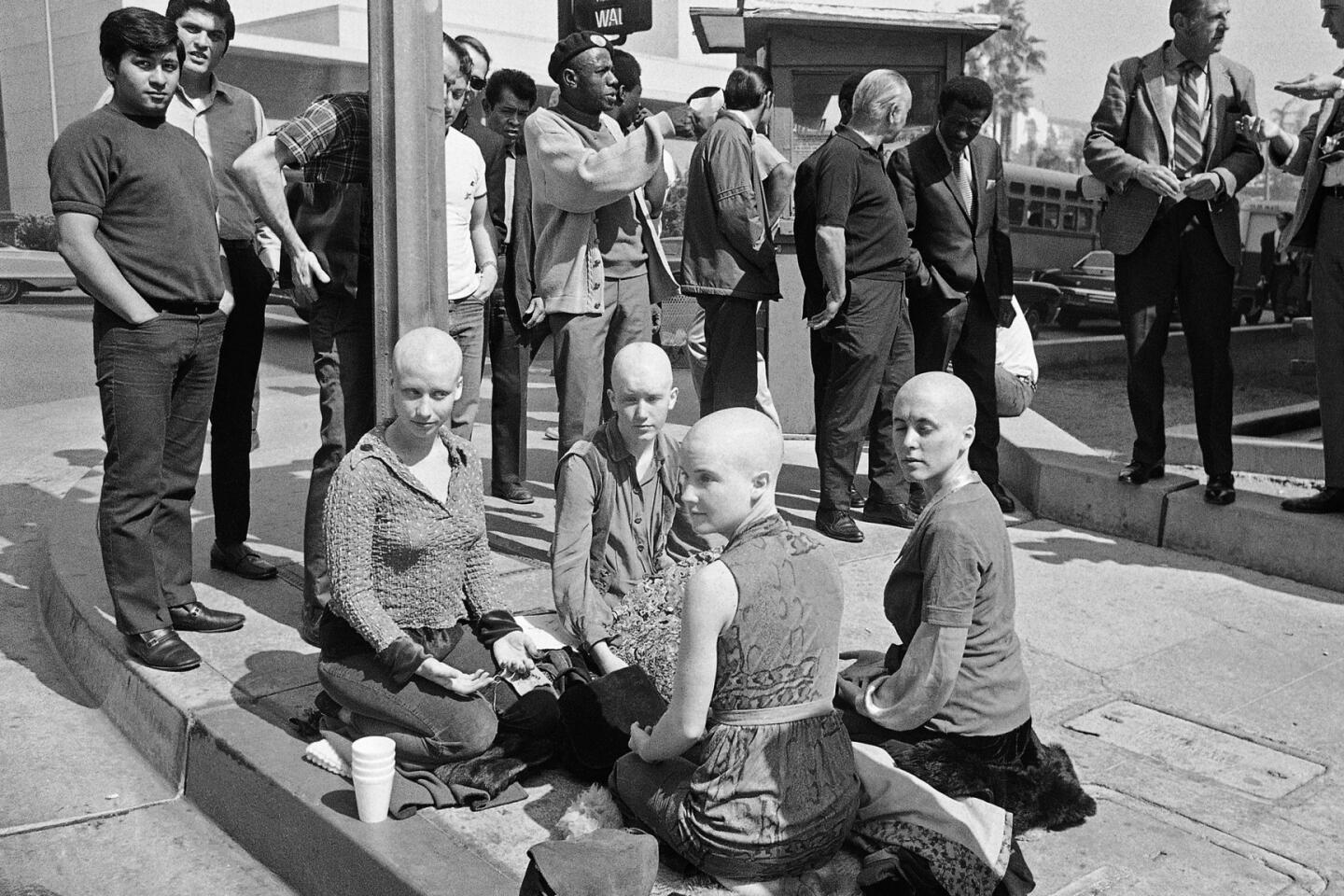

A group of young female followers with shaved heads gathered outside the courthouse and conducted a 24-hour vigil for Manson. One morning Manson entered the court room with an X carved into his forehead and his followers soon did the same. During the trial, Manson jumped over his attorney’s table and made a dash for the bench. While the bailiffs were dragging him out of the courtroom, Manson shouted to Judge Charles H. Older, “In the name of Christian justice, someone should chop off your head!” The judge began packing a .38-caliber revolver under his robe. Van Houten’s attorney, Ronald Hughes, disappeared during the trial and was later found dead. Prosecutors suspected he was another Manson victim.

Manson became a metaphor for evil, and evil has its allure.

— Vincent Bugliosi, lead prosecutor

Bugliosi argued during the trial that Manson orchestrated the murders as part of a plan to spark a race war that he called Helter Skelter. Blacks would win the war even though, according to Manson, they were inferior to whites. Then he and his followers would survive by living underground near Death Valley and would eventually take over power. In a later trial, Manson was convicted in the slayings of musician Gary Hinman and Donald “Shorty” Shea, who worked at the San Fernando Valley ranch where the family lived for a time.

In 1972, the death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment when the state Supreme Court abolished the death penalty. Since then, Manson and his followers have been eligible for parole hearings. Only one of those convicted in the nine murders — Steve Grogan, who was involved in the Shea shooting — has been paroled. Atkins died in 2009 while incarcerated in Chowchilla.

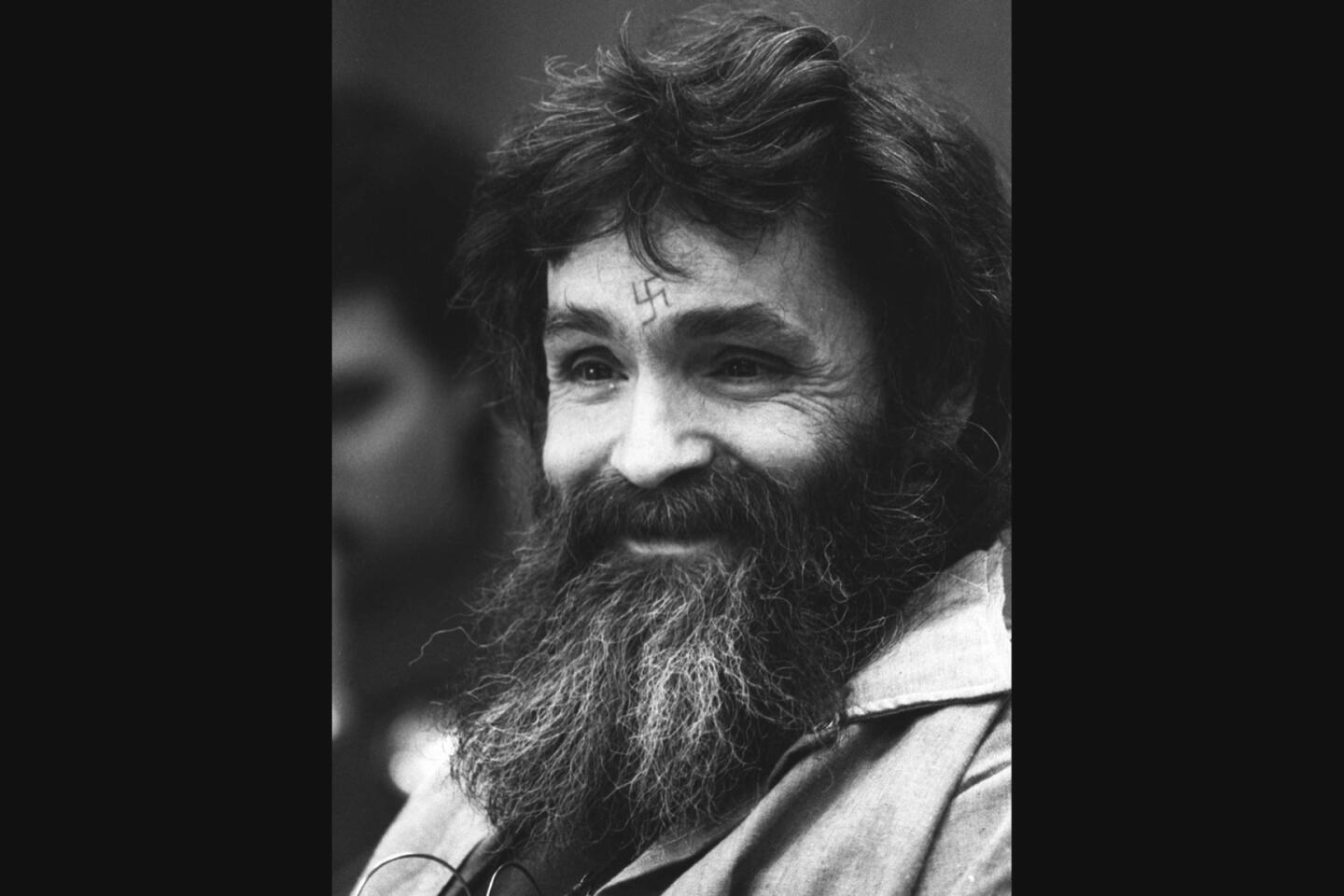

Manson — who had spent more than half of his life in prison before the conviction — was housed at Corcoran State Prison since 1989. He broke prison rules dozens of times for violations including possessing cellular phones and a hacksaw blade, throwing hot coffee at a staff member, spitting in a guard’s face, fighting, refusing to obey orders and trying to flood a tier in his cellblock. Long ago, he turned the X on his forehead into a swastika. He was denied parole 12 times and had numerous disciplinary violations. His last parole hearing was in 2012, which he declined to attend.

Doris Tate, Sharon’s mother, became a victims’ rights advocate after the murders and helped collect more than 350,000 signatures on petitions opposing parole for Manson and his followers. After her death in 1992, her daughter Patti Tate appeared at Manson family hearings opposing parole.

More than 40 years after the mass murders, Manson — whose wild-eyed stare was immortalized on a Life magazine cover — remains a figure of fascination, a homicidal anti-hero for a new generation. Rock groups have played songs that he wrote. Merchants peddle T-shirts bearing Manson’s likeness, as well as belt buckles, caps, necklaces, rosaries and cigarette lighters. Manson memorabilia is sold on the internet.

“Manson became a metaphor for evil, and evil has its allure,” said Bugliosi, who wrote — with Curt Gentry — the bestselling nonfiction book “Helter Skelter” about the case. “People found him so fascinating because unlike other mass murderers who did the killings themselves or participated with others, Manson got people to kill for him.”

Manson received in prison an average of four fan letters a day, said Stephen Kay, who helped prosecute the case. When he turned 80, Manson and a 27-year-old fan obtained a marriage license. But it expired before the paperwork was completed.

There’s these young people today who are intrigued by his mystique ... But they don’t know what he’s really about, what he really did.

— Stephen Kay, helped prosecute the case

Kay said he attended 60 parole hearings to argue against Manson family members’ release before retiring from the district attorney’s office in 2005. Manson, Kay said, evolved into the focal point of satanic worship in the U.S.

“At one parole hearing outside San Quentin in the late 1980s, there were about 40 satanic worshipers dressed in black outside the prison chanting for his release,” Kay said. “Then there’s these young people today who are intrigued by his mystique since he’s America’s most famous criminal. But they don’t know what he’s really about, what he really did.”

Manson has been portrayed as the dark prince of the counterculture, the sinister consequences of a permissive era. The man and his crimes, however, are more a product of parental neglect, a failed foster care system and barbaric juvenile justice institutions.

Charles Manson was born Nov. 12, 1934, to an impoverished 16-year-old single mother named Kathleen Maddox. “No Name Maddox” appeared on the Cincinnati hospital’s birth certificate because the father had not been identified. His mother later was briefly married to a man who provided his stepson with a last name.

Shortly after Manson was born, Kathleen would tell relatives she had to run off for an hour or two, leave her son, and then return days or weeks later. When Manson was 5, his mother and her brother robbed a West Virginia service station and knocked the attendant unconscious with a Coke bottle. They were sentenced to five years in state prison. Manson was sent to live with an aunt and uncle. The happiest day of his life, he has said, was when his mother was released from prison. The feeling did not last long. He spent the next few years in tow, as his mother embarked on a journey through the Midwest, staying at a series of seedy hotel rooms and drinking heavily.

“By the time I was 12 I’d missed a lot of school, seen a few juvenile homes and no longer believed all my mom’s lovers were ‘uncles,’ ” he said in “Manson in His Own Words,” as told to Nuel Emmons. “One night I was awakened by the sound of [my mother and her current boyfriend] arguing. The words I remember most were his: ‘I’m telling you, I’m moving on. You and I could make it just fine, but I can’t stand that sneaky kid of yours.’ ”

His mother then attempted to place him in foster care, but no home was available, so the court sent Manson to a facility for troubled boys in Indiana. After 10 months, he ran away and returned to his mother, but she told him she didn’t want him. He ran off again, broke into a grocery store for enough cash to rent a room. After a series of burglaries, armed robberies, arrests and escapes from juvenile institutions, he was sent to a reform school in Indiana.

Manson was only 13, a small, slight, unhappy boy. He was frequently beaten with a strap by the staff and, shortly after he arrived, he was gang-raped by several older boys, he wrote. After a guard discovered the assault, he told Manson, “You, Manson, go wash your face and stop all your crying.”

During his three years in reform school, he ran away 18 times. By the time he was 18 he had been transformed from prey into predator. He was convicted of holding a razor blade to the throat of another boy and raping him. When he was finally released from reform school, he wasn’t out for long. He was arrested for stealing cars and violating parole and, at the age of 22, was sentenced to his first term at an adult prison: three years at the Terminal Island federal penitentiary. Older inmates taught him how to be a pimp, and during a few brief interludes between prison sentences he had turned a few girls out on the street.

Manson’s music and his quasi-spiritual rap, which later had impressed followers, were forged during his stays in prisons during the next decade. At McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary, he met Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, the sole survivor of the Ma Barker gang, who taught him how to play steel guitar. He read science fiction and books on Eastern religion books and learned about Scientology from a bank robber. On a prison form, he listed his religion as “Scientologist.”

Manson was married twice before he was sentenced to the Terminal Island federal prison and had a son with each wife.

In 1967, he was scheduled to be released from Terminal Island with no friends or family on the outside who wanted to see him, no trade and no prospects for a job.

“I told the officer who was signing me out, ‘You know what, man, I don’t want to leave!,’” Manson wrote. “‘I don’t have a home out there! Why don’t you just take me back inside.’ The officer laughed and thought I was kidding. ‘I’m serious, man! I mean it, I don’t want to leave!’ My plea was ignored.”

He hitchhiked to Berkeley during the Summer of Love, a time when the Bay Area was a mecca for young, idealistic hippies. They were easy prey for a street-smart conman like Manson. He soon put to use everything he had learned in prison. He played guitar on the street to attract women, intrigued them with his metaphysical monologues and, like the pimp he once was, manipulated and exploited young women and used them to attract male followers.

The followers took copious amounts of LSD, but Manson always abstained or took a much smaller dose and then orchestrated orgies in order, he claimed, to break down sexual taboos. The family survived by petty crimes and raiding supermarket dumpsters. Before the Summer of Love was over, Manson had eight followers, most of them women. They piled into an old school bus and roamed the West Coast before ending up in Los Angeles. In the spring of 1968, two female Manson family members who were hitchhiking were picked up by Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys. They introduced him to Manson and the family briefly lived with Wilson at his Pacific Palisades home. Wilson introduced Manson to Terry Melcher, a record producer who was Doris Day’s son, and Manson played a few of the songs he wrote. Melcher had considered signing him, but eventually passed, embittering Manson. The family eventually moved to the Spahn Ranch, a little-used 500-acre property in the Santa Susana Mountains above Chatsworth.

In August 1969, Manson handed Watson a gun and a knife. “He said for me to take the gun and knife and go up to where Terry Melcher used to live,” Watson testified. “He said to kill everybody in the house as gruesome as I could. I believe he said something about movie stars living there.”

There was a secondary motive for the Tate murders, Bugliosi wrote in “Helter Skelter”: “As Susan Atkins put it ... ‘The reason Charlie picked that house was to instill fear into Terry Melcher because Terry had given us his word on a few things and never came through with them.’ But this was obviously not the primary motive, since ... Manson knew that Melcher was no longer living at the [house].”

Along with Tate, they killed Jay Sebring, a Hollywood hairdresser; Voytek Frykowski, a friend of Polanski; Abigail Folger, Frykowski’s girlfriend and the heir to the Folger coffee fortune; and Steven Parent, 18, who was visiting the resident of the guest house and was just leaving the property.

The next night Manson led followers to a Los Feliz neighborhood he was familiar with, picked a house at random and tied up the LaBiancas with leather thongs. After Manson took off, the couple was murdered.

“Many people I know in Los Angeles,” Joan Didion wrote in “The White Album,” “believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on Aug 9, 1969, at the exact moment when the word of the murders ... traveled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true.... The paranoia was fulfilled.”

More than 40 years later, the notoriety of Charles Manson and the murders he plotted endures.

“Most homicides and trials get a lot of attention and then fade,” Bugliosi said. “Maniacs who kill to satisfy their urges do not resonate. Manson was different. As misguided as the murders were, he claimed that they were political and revolutionary, that he was trying to change the social order, not merely satisfy a homicidal urge. That appeals to the crazies on the fringes of society.”

Manson was nonchalant after he was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to San Quentin’s Death Row. He told prosecutors they were simply sending him home.

“Prison is my home,” he once said in an interview, “the only home I ever had.”

Corwin is a former Times staff writer.

ALSO

Charles Manson dead at 83; here’s why his health crisis was shrouded in secrecy

Manson follower Patricia Krenwinkel’s bid for freedom denied, despite claims he abused her

Why death row doesn’t work and how Charles Manson changed the death penalty

Susan Atkins dies at 61; imprisoned Charles Manson follower

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.