California is bone dry. Will March bring more misery or a miracle?

- Share via

California, and Southern California in particular, is bone dry.

The calendar says spring officially begins with the equinox March 20, but the meteorological winter — consisting of December, January and February — is already in the record books. In other words, the wettest months are over. Let’s take a look at where the Golden State stands.

How dry?

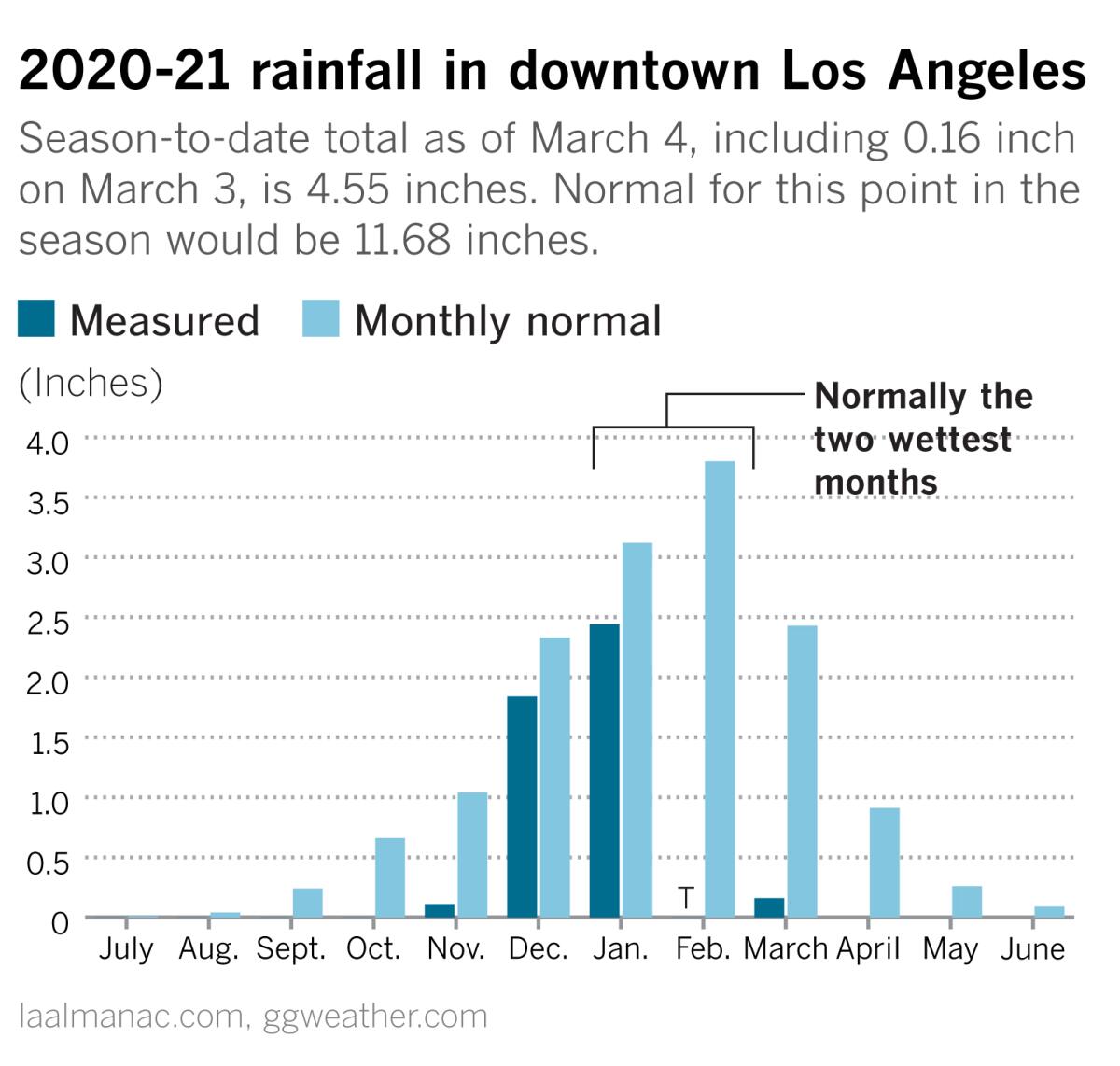

Downtown Los Angeles received 1.84 inches of rain in December, when it normally would get 2.33 inches. Some 2.44 inches of rain fell in January, when L.A. normally expects 3.12 inches. And just a trace (that is, not enough to be measured) fell in February, when 3.80 inches normally falls. January and February are normally the two wettest months in L.A., after which the chances for rain diminish rapidly with the approach of spring and the end of the rainy season.

Just 4.55 inches of rain fell over Los Angeles as of Thursday, when it normally should have received 11.68 inches to date.

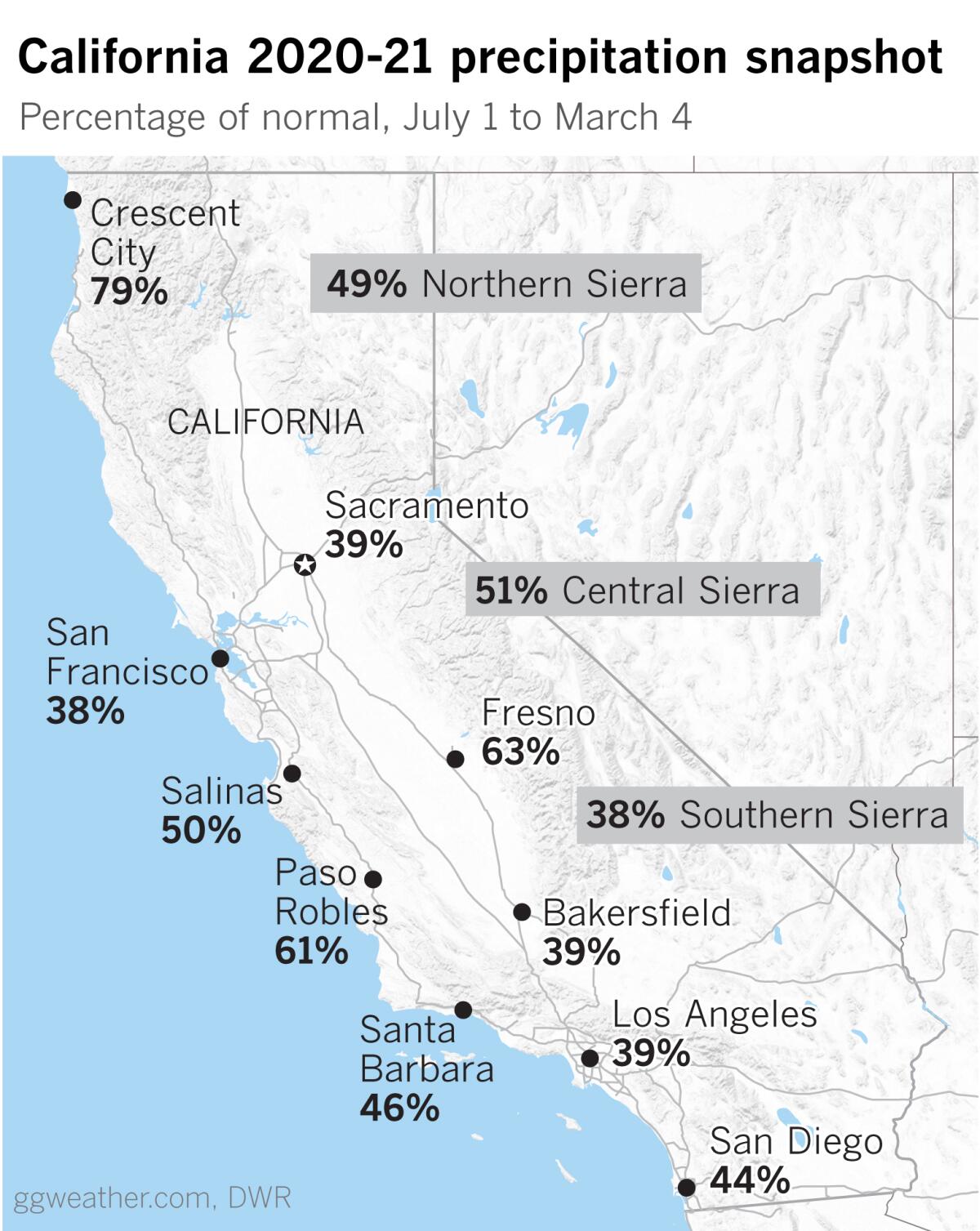

It’s not just Southern California

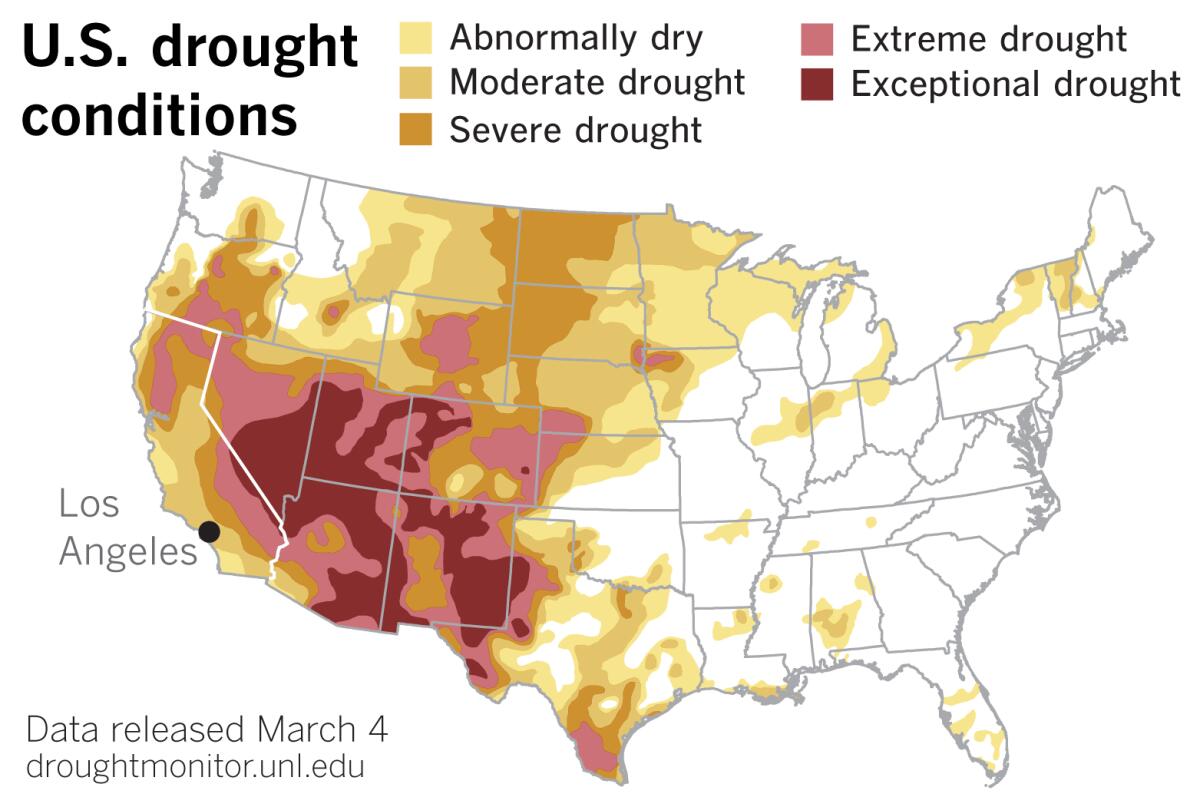

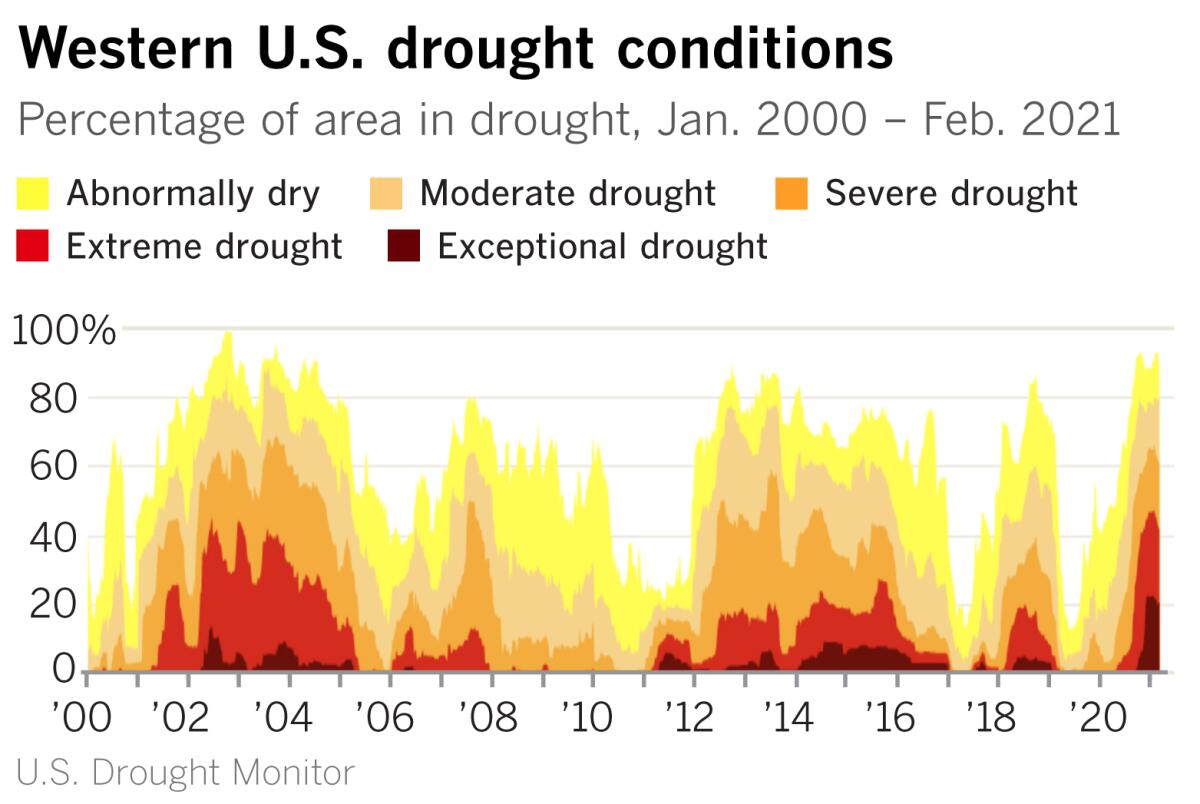

Los Angeles and Southern California have lots of company in this respect. The state and the West are gripped by persistent drought, including large areas of exceptional drought in the Southwest, where the 2020 monsoon was a no-show, as the most recent U.S. Drought Monitor report shows. Many water agencies are discussing water conservation measures, and the North Marin Water District is considering voluntary and mandatory water conservation orders.

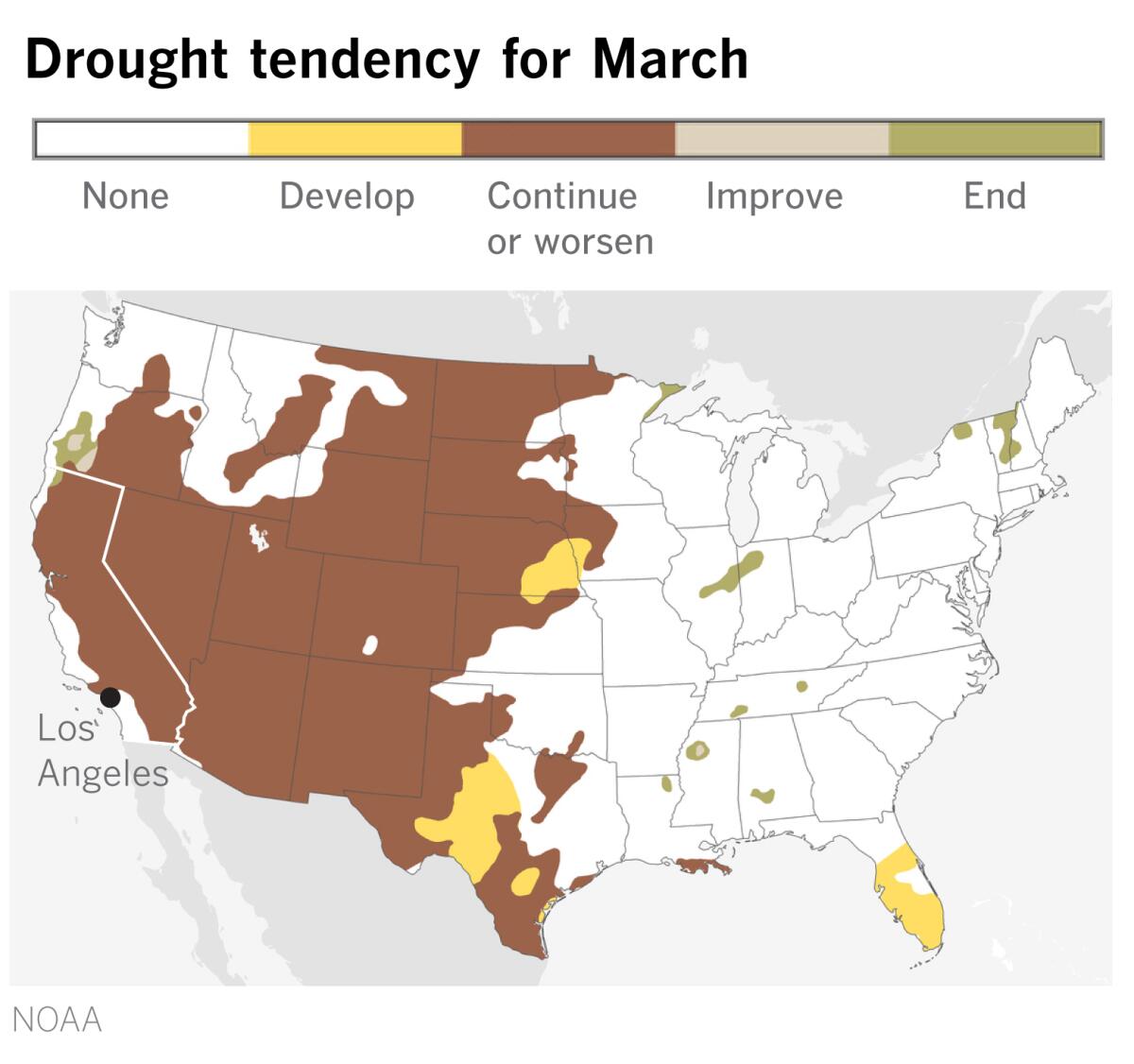

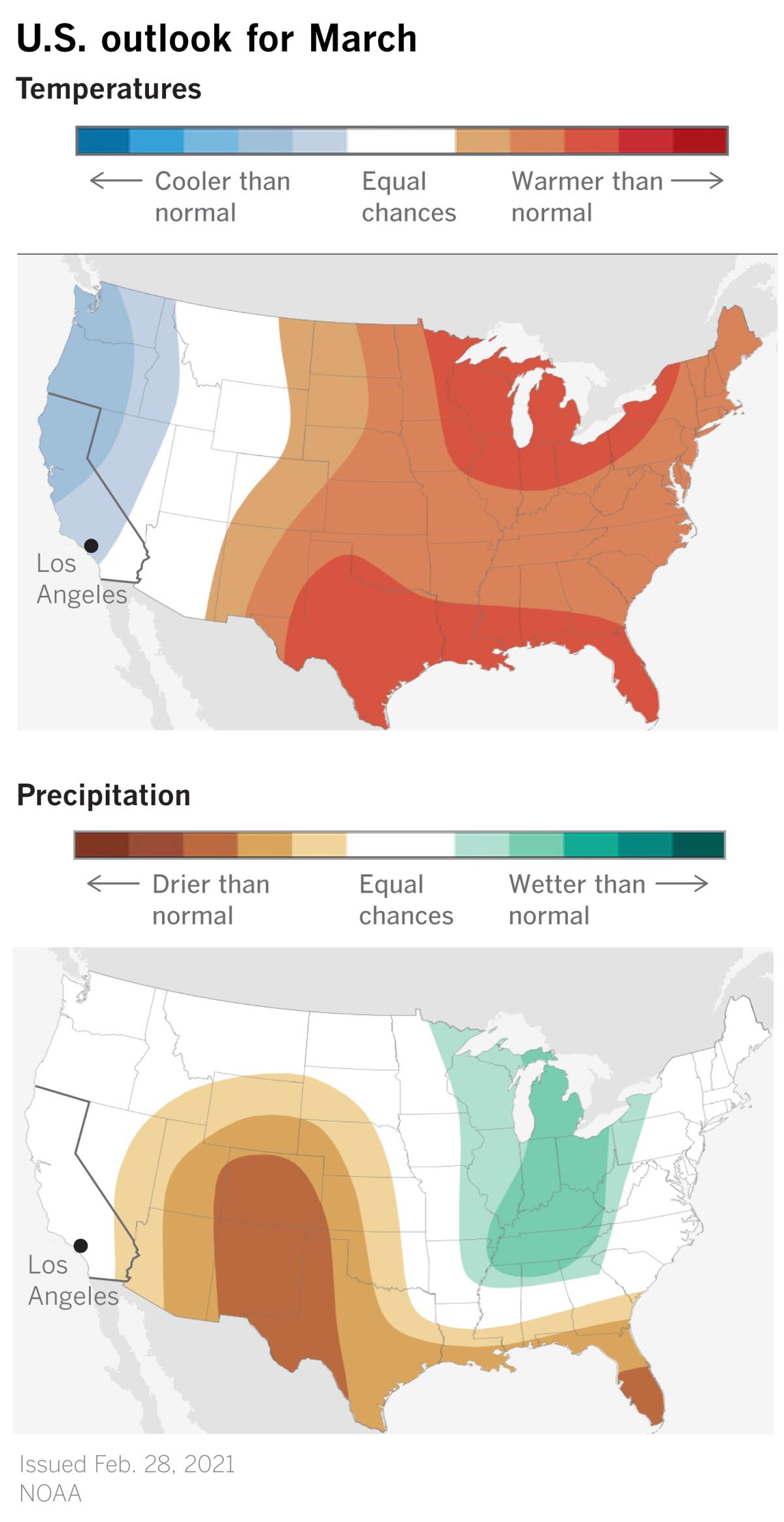

Talk of conservation is likely to spread if the drought persists, as is expected, according to the outlook below.

Why is this happening?

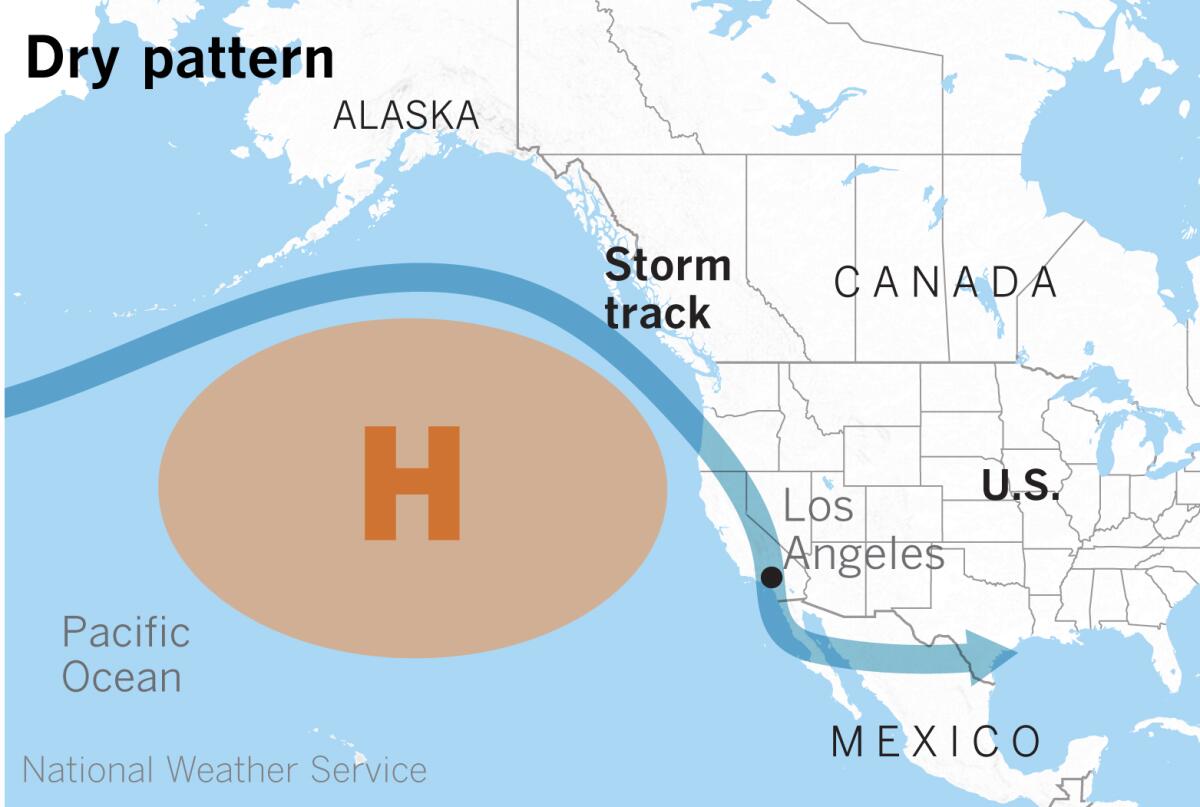

California has been plagued by an unusual and persistent upper-level ridge of high pressure in the Pacific off the West Coast. This has been blocking the storm track since last fall, making for a dry pattern that favors Santa Ana winds.

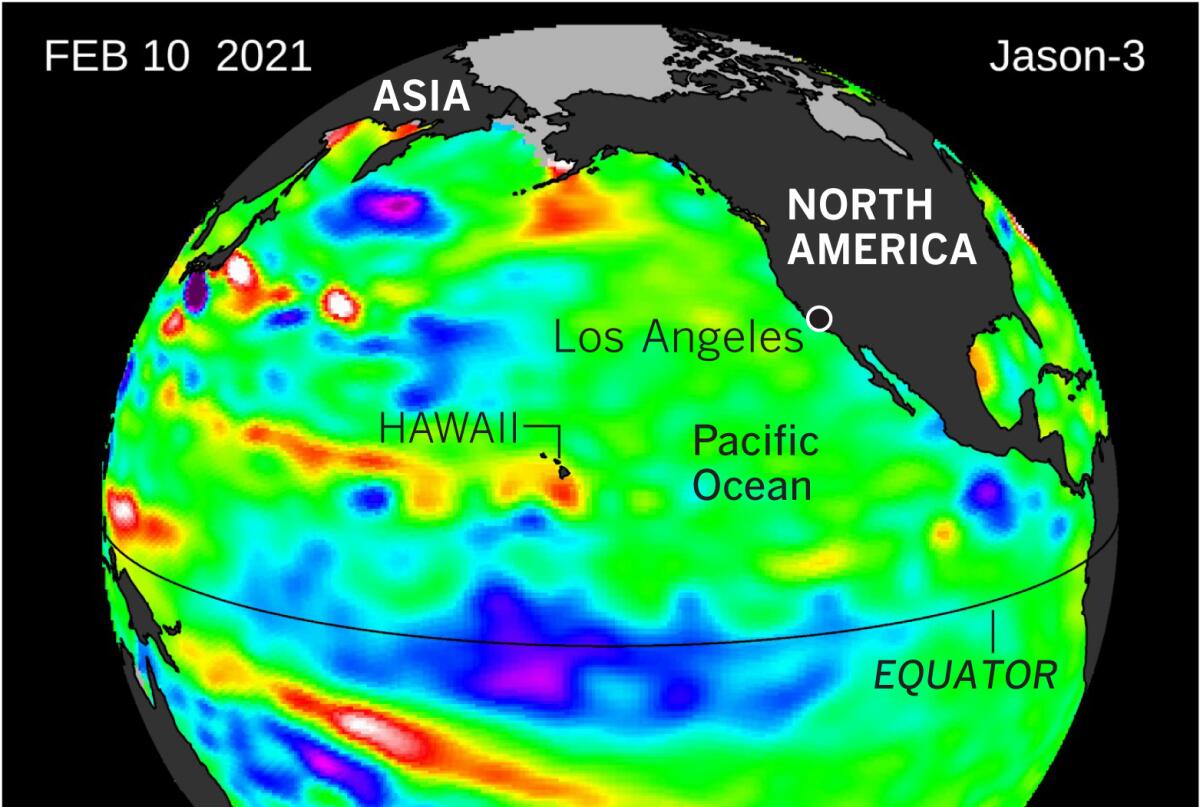

This pattern is consistent with La Niña, which is still in effect in the equatorial Pacific. La Niña occurs when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific are below average. Easterly winds over that region strengthen, and rainfall usually decreases over the central and eastern tropical Pacific and increases over the western Pacific, Indonesia and the Philippines. This pattern favors warmer, drier conditions across the southern part of the U.S. and cooler, wetter conditions in the northern U.S.

In the big picture, the drought in the West can be seen as a long-term event, interspersed with a few wet years, that has continued over the last two decades. The longer it lasts, the worse it gets, as climatologist Bill Patzert points out. It affects groundwater and the wildfire situation, and the effects build over time. The longer the drought goes, the greater the push for conservation.

Not only is the drought stubborn, as the chart above shows, but the dramatic rise in extreme and exceptional drought after 2020, compared with the extremes in other years since 2000, is also notable.

What are the chances of a ‘March miracle’?

The outlook for March isn’t overly encouraging. Cooler-than-average temperatures are forecast in California, and the Southwest either looks drier than average, or has equal chances of being wetter or drier than average. In other words, no “March miracle” appears to be in the offing.

“Now that the ides of March are approaching, the snow and rain drama is whether California will have March misery or a miracle,” Patzert said.

Last-minute relief in March and April 2020 brought Southern California up to about normal, but record-breaking heat in the summer and fall intensified the existing widespread drought throughout the West.

Given that the seasonal average for downtown Los Angeles is 14.93 inches, “there is only one March in the historical record that would put downtown L.A. above average. That was the super El Niño year of 1884, the wettest March and rain year in our history,” Patzert said. “That El Niño delivered colossal March rains of 12.36 inches. In the present modest-to-strong La Niña year, that would be the longest of shots. Think of shooting a basket from the Forum to Staples Center.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.