Column: America vanquished the ‘ancient atrocity’ of child labor. Republicans are bringing it back

- Share via

Among the most heartfelt goals and proudest achievements of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was the eradication of child labor.

In 1933, in signing a textile industry code that outlawed the employment of children under 16 in sweatshops, FDR crowed that “after years of fruitless effort and discussion, this ancient atrocity went out in a day.”

Conservatives and Republicans, who have tried for decades to undo such cornerstones of the New Deal as Social Security, have lately turned their efforts to resurrecting this “ancient atrocity.”

This permit was an arbitrary burden on parents to get permission from the government for their child to get a job.

— Spokeswoman for Arkansas Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, defending her loosening of child labor protections

In the last two years, 10 states, mostly Republican-controlled, have enacted or introduced laws rolling back child labor restrictions. Bills to do so have been introduced in six Midwestern states — Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, and South Dakota.

The charge has been led by Arkansas, where in March Republican Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a law repealing a rule that required children under the age of 16 to verify their age and obtain the written consent of a parent or guardian before obtaining a work certificate. Employers had to provide state officials with a job description and schedule.

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

A Sanders spokeswoman defended the law by stating that “this permit was an arbitrary burden on parents to get permission from the government for their child to get a job.” The spokeswoman said that all other laws “that actually protect children still apply.”

Children’s advocates observe, however, that the new law eliminates an important enforcement tool, leaving the door open for “the exploitation of children and youth under the age of 16 to perform dangerous jobs, often in hazardous work conditions,” in the words of Dennis Lee, a spokesman for the Catholic Diocese of Little Rock.

Make no mistake: The rollback of child labor protections isn’t a matter of streamlining unnecessary regulations. It’s a moral test for America.

Children are the most easily exploited group in the U.S. economy, especially when they’re members of low-income or migrant households. They can be paid less than adults doing the same work, be oppressed and manipulated by unscrupulous employers, and be less inclined to fight back against employers over workplace safety issues.

The promoters of these rollback laws love to depict them as blows for parental rights, as Sanders’ flack put it — keeping an oppressive government from getting in the way of sensible kitchen-table discussions between parent and child. The impression they put forth is that silly, outdated regulations are keeping teenagers from acquiring a work ethic while helping out the family budget by scooping ice cream during their summer breaks.

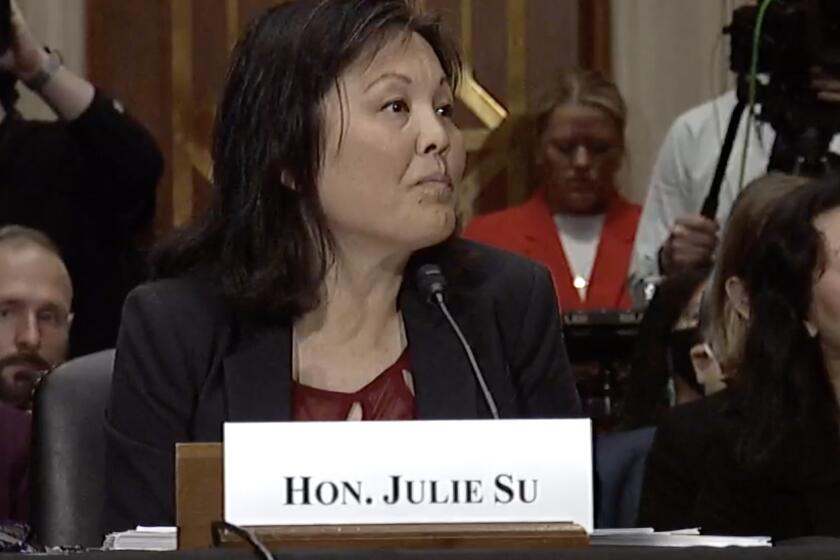

Julie Su’s accomplishments make her a spectacularly qualified nominee for Labor secretary. That’s exactly why Republicans — and some Democrats — will do their best to block her confirmation.

That’s a smokescreen. If it were so, then we wouldn’t see the rollback being pushed by lobbyists for home builders, supermarkets, restaurants and bars, or by Americans for Prosperity, a Koch-affiliated group. All those outfits have been behind the campaign for more child labor, the pro-labor Economic Policy Institute has shown.

As the Washington Post reported, a key backer is the right-wing Foundation for Government Accountability, which provided the sponsors of the Arkansas legislation with the draft law.

The foundation, which is backed by right-wing funding sources including the Ed Uihlein Family Foundation, the Sarah Scaife Foundation and the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, has lobbied against Medicaid expansion and for work requirements for food stamps, among other goals.

Sanders could not be unaware of the reality undergirding the rollback of child labor protections. Only weeks before she signed the Arkansas law, the U.S. Department of Labor fined Wisconsin-based Packer’s Sanitation Services, which provides workers to clean slaughterhouses, for employing more than 102 children ages 13 to 17 on overnight shifts under dangerous conditions in eight states, including two sites in Arkansas.

The agency said the “systemic” child labor violations “clearly indicate a corporate-wide failure by Packer‘s Sanitation Services at all levels.” It assessed the company only $1.5 million, the maximum permitted by law.

Packer’s Sanitation was acquired by the giant private equity firm Blackstone in 2018. In February, when the Department of Labor levied the $1.5-million fine, a Blackstone spokesman said Packer’s “has an absolute zero-tolerance policy against employing anyone under the age of 18 and is fully committed to ensuring it is enforced at all local plants.”

Packer’s doesn’t exactly have a pristine reputation. Since Blackstone acquired the firm, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration has opened investigations into at least four amputations and three fatalities among its workers, including one decapitation. That’s according to the Private Equity Stakeholders Project, a nonprofit watchdog.

The statutory penalty of $15,138 per child is “not high enough to be a deterrent for major profitable companies,” the agency said. The evidence for that could not be clearer. The agency says it has detected “a 69% increase in children being employed illegally by companies.”

Starbucks promotes itself as a friendly place to get a latte or caffeinated milkshake, but behind the smiles it’s been a leader in bare-knuckled union-busting.

In the last fiscal year alone, the department found 835 companies employing more than 3,800 children illegally. That has prompted the agency to announce a crackdown on violators of rules outlawing the employment of minors in “oppressive child labor” dating back to the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

The bills being introduced around the Midwest would expose children to working conditions that even adults might find harsh. A Minnesota bill would allow 16- and 17-year-olds to work on construction sites, according to a roundup of proposed measures by the pro-labor Economic Policy Institute.

Other proposals extend permissible work hours for minors, allow them to serve alcohol or reduce their access to break time. A bill in the Iowa Legislature would remove prohibitions on minors operating power saws or working in slaughterhouses or meatpacking or rendering plants, in mining, or in roofing or demolition, as long as they were doing so in connection with “work-based learning or a school or employer-administered, work-related program” — an obvious loophole.

(In a rare sign of rationality, the bill’s Republican sponsors removed a provision that would have immunized employers from civil liability if a student were sickened, injured or killed due to negligence by the student or employer.)

What’s really going on in workplaces employing child labor? If you’re prepared to be shocked and nauseated, feel free to read what Labor Department investigators said they found at three slaughterhouses in Nebraska and Minnesota that Packer’s Sanitation supplied with child labor. (Packer’s Sanitation didn’t deny the findings when it signed a consent order that included the $1.5-million fine.)

Children as young as 14 were working through the night on graveyard shifts cleaning machinery on the “kill floor.” Some didn’t clock out until 5 a.m. or 7 a.m.

They were working with machines such as a head splitter, a hydraulic-powered apparatus designed to “swiftly and cleanly drive [a] blade through the cradled head” of an animal; a bandsaw with the power to “split cow carcasses in half lengthwise”; and other “meat slicers, knives, or grinding machines.”

Their tasks involved their standing in pools of water on surfaces made slippery by animal fat, amid deafening noise and visibility-obscuring clouds of steam, cleaning equipment with “hoses, steaming hot water” and a “heavy-duty caustic cleaner” that gave the workers “serious chemical burns.” Then the children went to school; at least one fell asleep in class.

The company supervisors interfered with the agency’s investigation by trying to prevent them from taking photos or videos, even though the inspectors’ warrants expressly allowed it. The plant supervisors stood or sat nearby during the inspectors’ interviews, glowering at the child workers to discourage them from talking, often successfully.

Noncompete clauses push down wages and trap workers in lousy jobs, so of course they’re beloved by employers. The FTC wants to change that.

The Department of Labor cited federal law and regulations that prohibit employing anyone under 18 in any occupation designated hazardous, which includes cleaning “power driven machinery” such as “food slicers, food grinders, food choppers,” or most work performed “at slaughtering and meatpacking establishments.” Minors are specifically barred from doing work “on the killing floor,” the regulations say.

Children under 16 can’t be employed after 7 p.m. or for more than three hours a day when school is in session.

In the Packer’s case, inspectors had to conduct all their interviews with child workers in Spanish, a indication that the children were likely from migrant households.

Is there any excuse for easing laws against child labor that have been in place for as long as 85 years? Obviously not. The eradication of child labor was something Americans could be proud of, once upon a time.

The advocates of putting children to work and removing enforcement tools are turning a blind eye to the hazards of child labor. They congratulate themselves for taking government off the backs of working families, but their goal is just to make it easier for unscrupulous businesses to saddle up.

More to Read

Get the latest from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and more from a Pulitzer Prize winner.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.