From the Archives: ‘Cuckoo’s Nest’ revisited

One of several questions a film critic gets asked, invariably through clenched teeth and in accusing tones, is how come you only see a picture once before you write about it?

A simple but heartfelt answer is that doubling the 200 or so movies the reviewer sees in a year equals 400 or so and raises impossible hob with alternate diversions like eating and sleeping. The second answer is that many of those 200 movies reveal all they have to reveal the first time through — in the first 30 seconds, maybe — and watching again would qualify as cruel and unusual punishment.

But it is also almost always true that a good picture, seen again, looks better; a bad picture seen again looks even worse, and a middling picture reveals its shortcomings with a sad clarity.

Most of the critics I know are only too eager to see again (and again) a movie that has really knocked them out, because a genuinely exceptional movie has, almost by definition, a density of texture in the sense of its own rhythm and dynamics — a riches of calculation easier to discern the second time around, after the original emotional jolt is over.

Having written about “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” only last Sunday, I saw the film again this week. The iron law of the good ones look as good or better was in force. The quality of the acting by a cast that is not a cast but a disciplined ensemble is overwhelming.

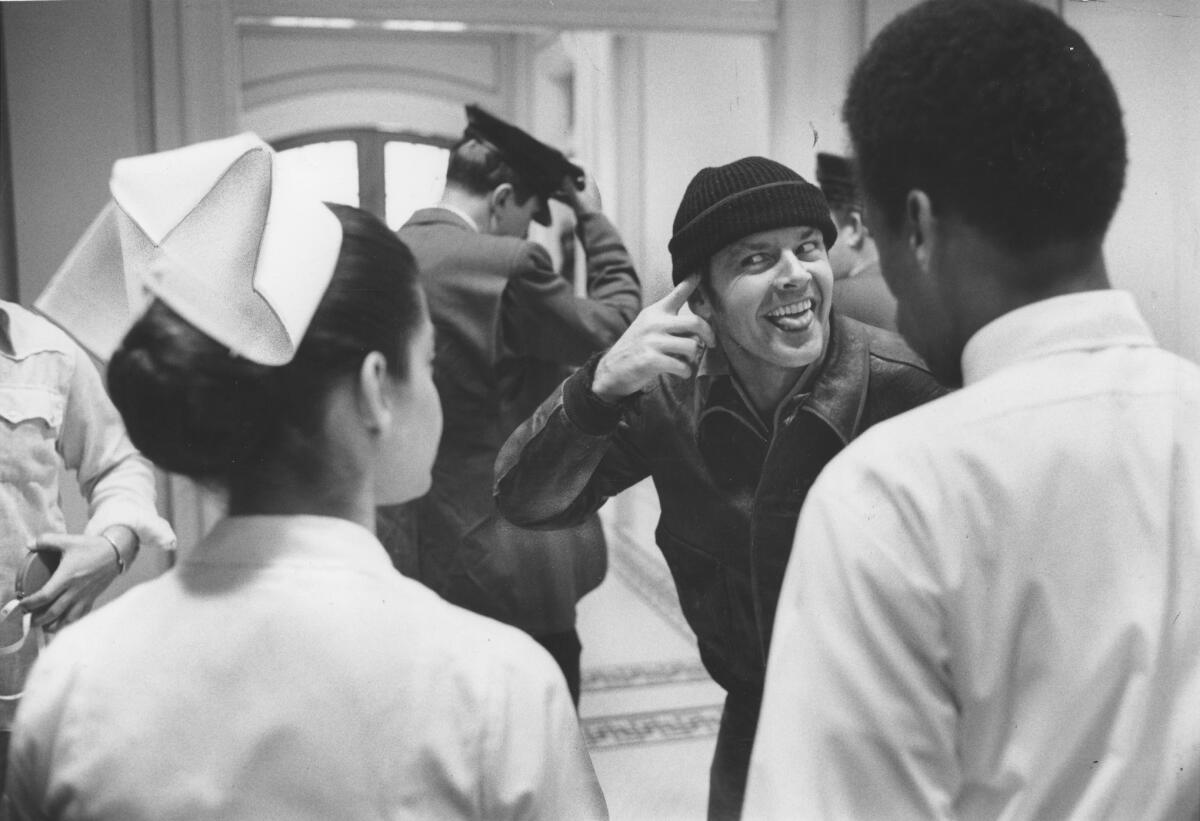

It is both too easy and impossible to portray madness or any of the variations and degrees of it. I can’t recall ever having seen so many actors convey so well the pain, the innerness, the quick rages and sudden collapses of the walking emotional wounded. It is as if Jack Nicholson’s fellow inmates at this fictional asylum were reaching up from some pit of despair toward the downstretching hand of sanity/reality. There are moments of touching, times of taking hold. Then the contact is broken and the men slip back into their various retreats from the world and from relationships they can’t handle.

What is miraculous as acting is that the reachings and the slippages are for the most part not large and expansive but as small and private as a sigh. Withdrawal is as subtle as a pulling at an eyelid, a slow exhaling of cigaret smoke, a pursing of lips.

Nicholson is almost the only identifiable actor in the film, and it is in box office terms a star performance likely to make “Cuckoo’s Nest” one of the largest successes of the year despite its hard contents.

But it is also the finest of all the fine portrayals Nicholson has already given us. Watching him again, it is astounding to see how he can regulate, as he might set the thermostat, the intelligence of the character he is playing.

This subtle, amiable jailbird on temporary leave to the funny farm is saner than the men around him but he’s not necessarily brighter. The eyes narrow with pleasure in his own craftiness and they go blank (if only for a moment) when a kind of fear cuts through the cocky pose. There is an almost continuous succession of scenes in which Nicholson sketches this idler, lover, jokester, manipulator, con man, gambler, loner.

His sudden chortling glee when he discovers that he is not the only con man in the joint and has in fact been fooled by a master is an explosion of thigh-slapping boyish delight. Even behind the façade of the king-of-the-hill guardhouse lawyer with a banty walk there is an impression not of a man more serious but of a man who, by God, wants to grab out of life what he can, without a lot of worry about or confidence in tomorrow.

“One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” builds to a carousing escape party that ends in a shock and several kinds of tragedy. At first viewing the resolution of the scene is baffling, contradictory and seemingly arbitrary.

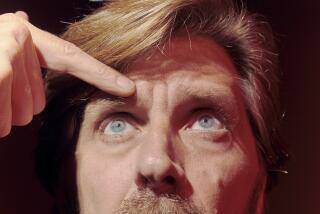

Not the least of the uses of a second viewing is that, knowing what is coming, you look for clues. And sitting again through “Cuckoo’s Nest,” it seemed to me that the secret of the party — and the last triumph of Nicholson’s matchless characterization — were both to be found in one long-sustained and wordless take in which the camera holds motionless on Nicholson’s screen-filling face. The mouth grins faintly, and stops, and grins again, and the eyes grin, but are then shadowed by something very much like fear and irresolution before, sleepily, they smile again, in an oddly different, emptier way.

As acting it is superlative; as story it is a moment of truth — even if the bitter truth is that life is never as easy and simple as it ought to be.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.