Activists on trial as China steps up campaign against dissent

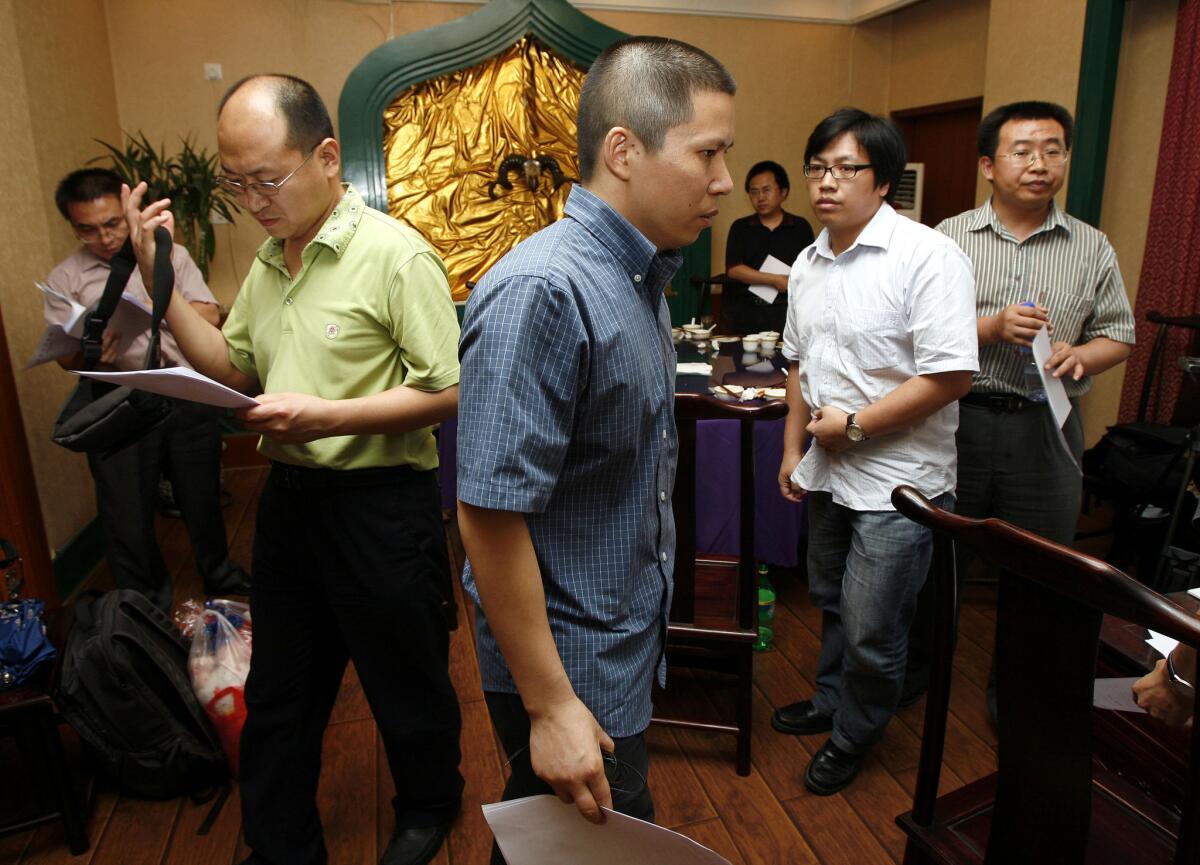

BEIJING — At least seven Chinese activists who have advocated for greater rule of law, fairer access to education and other issues are being put on trial this week as the government steps up a campaign against dissent.

The most prominent case is scheduled to open Wednesday morning in Beijing as lawyer Xu Zhiyong, founder of the loose-knit New Citizens Movement, goes to court on charges of gathering a crowd to disrupt order in a public place.

He is the highest-profile activist to be tried since Liu Xiaobo was sentenced to 11 years in prison on subversion charges in 2009. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Expectations had risen since then that new President Xi Jinping might be more open to free speech. But those hopes have largely been dashed, and a media blackout on Xu’s case has left most mainland Chinese unaware of the proceedings.

Prosecutors allege that Xu and others organized and incited hundreds of people to gather in front of government buildings and at train stations and universities in Beijing in 2012 and 2013. The demonstrators, the government said, unfurled banners and handed out leaflets about issues such as education reform and asset disclosure for government officials. The charges carry a maximum sentence of five years in prison.

But it is the wider spectrum of Xu’s activities that have probably have alarmed authorities, analysts and his allies say. Although Xu has been more circumspect in his public statements than Liu, he has encouraged events such as dinner gatherings at which participants discuss issues and make plans for action.

“They have been talking about a new sort of activism, the need to take new action, not only talk,” said Feng Chongyi, an associate professor of China studies at the University of Technology in Sydney, Australia, who studies Chinese political and intellectual movements. “The security people have made the judgment that they could be facing serious demonstrations. This is a preemptive strike.... They want to take out the leaders and organizers, and send a clear signal that no one is allowed to organize street protests.”

Xu’s rise to prominence began in 2003 when he became involved in what turned out to be a successful campaign to abolish rules that allowed police in large cities to arbitrarily detain people found without urban residency permits. His Open Constitution Initiative law firm took on some tough cases, defending the editor of a hard-hitting newspaper and representing parents whose children had been sickened or killed by milk additives. But in 2009, the firm was hit with tax evasion charges.

Xu then founded the New Citizens Movement, which he has said is aimed at treading “a new path for the Chinese nation, a path toward liberty, justice and love.”

In a 2012 essay, he described it as a political movement in which China “bids utter farewell to authoritarianism and completes the civilized transformation to constitutional governance,” a social movement to “completely destroy the privileges of corruption, the abuse of power, the gap between rich and poor, and to construct a new order of fairness and justice,” and a cultural movement to end “the culture of autocrats and subjects and instead create a new nationalist spirit.”

Xu was placed under house arrest in April, detained in July and formally arrested in August. His lawyer, Zhang Qingfang, said he visited Xu on Tuesday morning and that he was calm ahead of the trial. He added that Xu’s wife, Cui Zheng, who recently gave birth, was looking forward to the proceedings, if only because it would be the first time in more than six months that she would be able to see her husband.

Zhang said he and Xu planned to remain silent throughout the hearing to express their objections to what they regard as irregular and unfair procedures imposed by authorities, though Xu intends to deliver a concluding statement.

Among their main concerns, Zhang said, were prosecutors’ decision to hold separate trials for the activists and their refusal to allow witnesses to appear in court and be questioned. Xu’s trial is to be followed on Thursday and Friday by four cases against fellow activists in Beijing and the southern city of Guangzhou.

Prosecutors have listed 68 witnesses against Xu, Zhang said, but would permit only their statements to be entered into the official record. Zhang said his efforts to bring five defense witnesses to the courtroom were rejected.

“This whole trial is being conducted in a black box, where we cannot actually see the entire process,” he said. “I always hope and strive to represent my clients in a fair trial, but this is not fair, so I will keep silent.”

Zhang said he intends to release what would have been his defense statement after the trial concludes. Meanwhile, a number of other attorneys and academics, including Feng, have signed a petition calling on the judges hearing the cases to not allow “political interference to trump your obligation to justice.”

“We ask you to place your hand on your chest, where your heart beats, and ask yourselves whether you would deny that these are cases of political persecution,” the petition says. “Do you honestly believe these citizens have perpetrated the crimes they are accused of?”

Luo Lo, who has worked with Xu on education issues, said the situation for activists has become more dire in the last year. “In past years, putting out banners, organizing protests or petitions would not be suppressed so severely, but since the first half of 2013, the intimidation and police attitude has become much worse.”

Feng said that he met with Xu in Beijing before he began pushing the New Citizens Movement in earnest in the summer of 2012 and that for a brief time, Xu was optimistic that the new president, Xi, and the rest of the new generation of Communist Party leaders who rose to power in November 2012 would chart a different path than that of their predecessors. Xu was particularly encouraged, Feng recalled, by Xi’s comments on rooting out corruption among officials and abiding by the constitution.

Xu’s trial may prompt participants in the New Citizens Movement to pause and bide their time until a new issue arises that presents an opportunity to mobilize people, Feng said. But even a five-year sentence for Xu, he said, will not kill off the group and in fact may help make Xu a martyr of sorts for the cause.

“They will organize one way or another,” he said. “They will use the Internet and other new communication avenues to continue their work.”

Luo agreed that a conviction was unlikely to have much of a chilling effect.

“By arresting him, it shows that the environment for human rights in China is worsening. Look at the example of South Korea and Myanmar; such arrests only make people become more active,” Luo said. “Some people will be active against this movement, but more people will begin to speak out for it, so in a sense, this is all a good thing.”

Nicole Liu and Tommy Yang in The Times’ Beijing bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.