The mess in Venezuela didn’t happen overnight. Here’s how two successive presidents chipped away at democracy

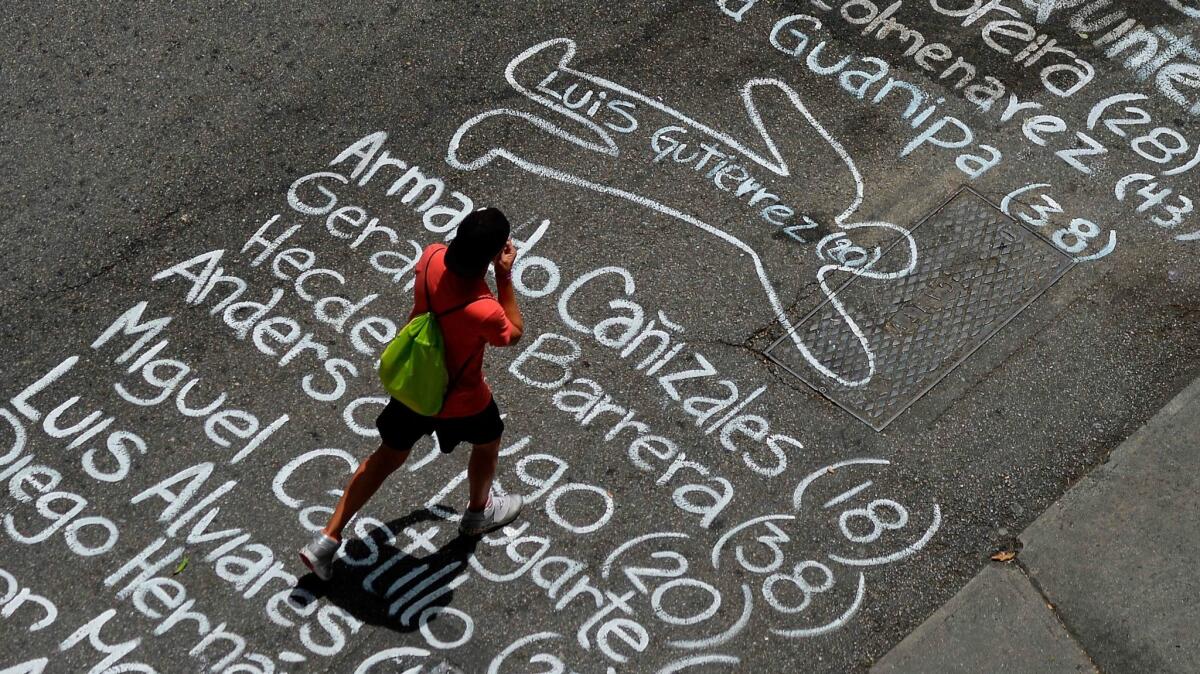

Reporting from Caracas, Venezuela — Venezuela has been gripped by near daily protests for the last 10 weeks, resulting in 69 deaths, 1,235 arrests and millions of dollars in property damage.

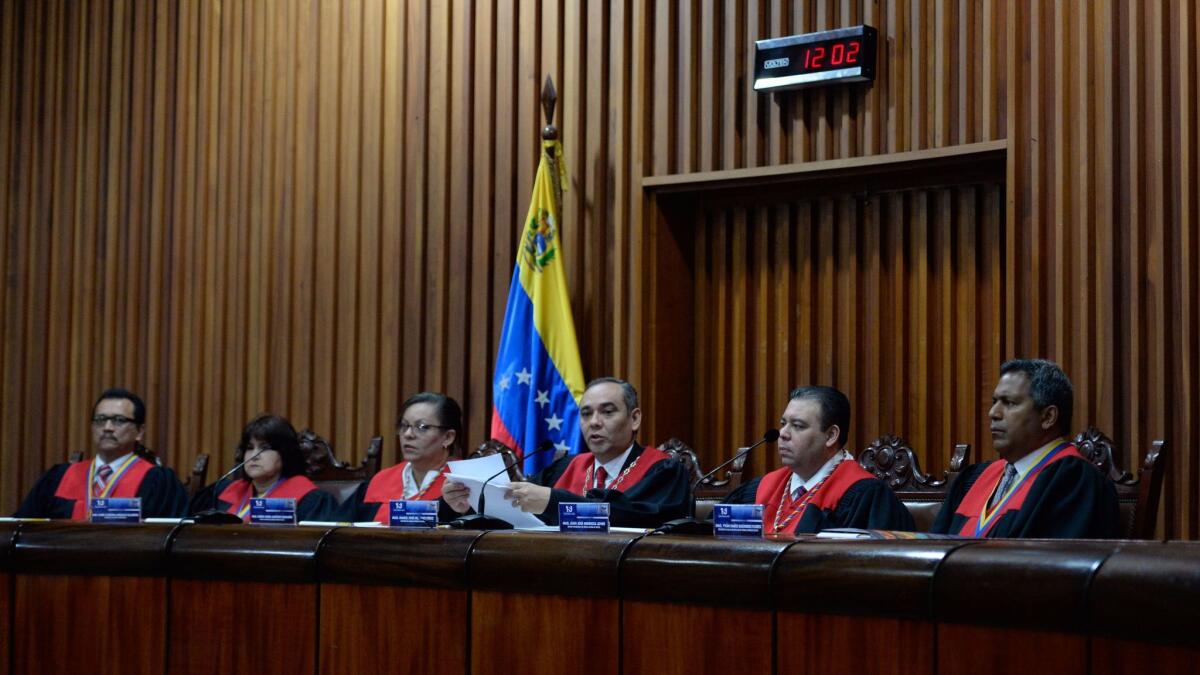

The demonstrations started in late March after the Supreme Court, which is controlled by President Nicolas Maduro, ruled that it was taking over the powers of the legislature and intensified a week later when the government disqualified a leading member of the opposition from running for office for the next 15 years.

But the protests have also been years in the making, as Maduro and his predecessor, the late Hugo Chavez, the founder of a socialist movement known as Chavismo, chipped away at democracy by canceling elections, shutting down news outlets and arresting political opponents.

Food shortages and rising crime have only added to the anger.

“This is a new chapter in the conflict between chavismo and the opposition, a chapter animated by the catastrophic government of Maduro,” said Luis Salamanca, a professor at Central Venezuela University in Caracas. “Citizens are struggling to make the government respect their constitutional rights.”

Public protests may be the only recourse left to the opposition, experts said.

“The cumulative effect of increasingly severe and blatant authoritarian measures can be seen in the wave of street protests in Caracas and elsewhere,” said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue think tank in Washington. “The opposition has pursued other avenues to press for change but has consistently hit a wall.”

Here are some ways that the government has worked to limit the opposition’s power:

Attacks on news media

In 2007, Chavez refused to renew the broadcasting license of RCTV, the most widely followed anti-government station, forcing it to shut down and sparking nationwide protests.

Since then, an estimated 300 independent small-town radio stations have either been shut down or forced to change to government-friendly formats, according to Marcelino Bisbal, a professor at Andres Bello Catholic University.

Globovision, the last television station to broadcast anti-government editorials, was forced to sell in 2013 after owners complained of mounting government fines and political harassment. The new owners are businessmen with ties to Maduro.

CNN, El Tiempo TV, NTN24 and other Spanish language cable channels that have criticized the government have been banned from broadcasting in Venezuela.

Maduro halted TV broadcasts of National Assembly sessions last year after the opposition won majority control.

In 2014, the largest daily newspaper, El Universal, was forced to sell to a government-friendly owner group.

Interference with the National Assembly

In nationwide elections in December 2015, opposition candidates won the two-thirds majority needed to control the National Assembly. That should have allowed the opposition sweeping powers to overturn Maduro’s decisions and take control of the budget.

But before the new congress was installed, Maduro added 13 new justices to the Supreme Court. With Maduro allies in control, the court then disqualified three newly elected assembly members from Amazonas state by claiming voting irregularities.

That deprived the opposition of super-majority powers in the legislature and preserved Maduro’s political potency.

In July 2016, after opposition leaders claimed the high court had presented no proof of voting irregularities, they installed the three Amazonas assembly members anyway. The court responded by declaring the congress to be in contempt and said that all laws passed from that point on were unconstitutional and thus null and void.

The Supreme Court gave all legislative powers to Maduro on March 29 and eliminated parliamentary immunity, making all members subject to prosecution. Domestic and international reaction to the ruling was so negative that the court reinstated immunity two days later. Maduro was allowed to keep his new powers.

Last month, he extended a state of emergency for an eighth straight two-month period, maintaining discretionary powers and the suspension of certain individual constitutional rights.

Electoral interference

Soon after the opposition-controlled assembly took its seats, the majority began a campaign to exercise its constitutional right to hold a recall election to remove Maduro from power.

Despite the collection of 1.3 million signatures in the first phase of the campaign last year, the Maduro-controlled National Electoral Council delayed the process so long that even if the opposition had won the vote, Maduro’s vice president would have served out his term ending 2019. The opposition then rejected the referendum.

Elections for state governors and mayors were supposed to have been held in December of last year. But the electoral council has postponed them and not set a new date.

Disqualification of opposition candidates.

One by one, leading opposition candidates have been disqualified from running for office, often on flimsy pretexts.

On April 7, the controller’s office said that Henrique Capriles, the governor of Miranda state who finished a close second to Maduro in the 2013 presidential reelection to replace Chavez, was ineligible to run for any public office until 2032 because of alleged misuse of funds. Capriles rejected the charges and described the action as a “coup” to eliminate a competitor in the 2019 presidential elections.

Leopoldo Lopez, a charismatic former Caracas borough mayor, was disqualified from running for office for six years starting in 2008 for alleged misuse of public funds. As the ban was running out, he was jailed in February 2014 on incitement of violence charges related to nationwide protests. He denied both charges.

Former assembly member Maria Corina Machado was disqualified from elections in 2015 on suspicion of planning to violently overthrow the government, a charge she has denied. She previously had been expelled from congress for attempting to speak at a meeting of the Organization of American States in Panama.

Liborio Guarulla, the popular opposition governor of Amazonas state and one-time Chavez follower, was disqualified on May 7 from running for any office before 2032. The electoral council said the reason was “administrative negligence.” Guarulla, a member of an indigenous community, dismissed the charges and leveled a curse against authorities “for trying to do us evil.”

Arrests and imprisonment of political leaders

Lopez, who is being held at a military prison near Caracas, is not the only politician arrested on charges that appear suspect.

In 2015, authorities arrested Antonio Ledezma, who was then mayor of metropolitan Caracas, and charged him with attempting to overthrow the government, which his family has described as ludicrous.

Yon Goicoechea, a former student leader who rose to prominence during 2007 demonstrations against the closing of RCTV, was arrested in August of last year and charged with possession of explosives. His wife, who rejected the charges, told reporters that her husband was tortured while in confinement.

Daniel Ceballos, mayor of San Cristobal, the capital of Tachira state, has been jailed since 2014, when authorities accused him of contempt of a court order to restrain protesters during a wave of demonstrations that turned violent. He denied any responsibility.

Special correspondent Mogollon reported from Caracas and Kraul from Bogota, Colombia.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.