Can another Fujimori win Peru’s presidency? Surge by opponent makes race a toss-up

Reporting from Lima, Peru — Just 10 days ago, Keiko Fujimori seemed to have an insurmountable lead in the race for the presidency of Peru.

In an intense runoff campaign, Fujimori emphasized her youth — she turned 41 in May — solid congressional backing and populist proposals, such as cracking down on rampant crime.

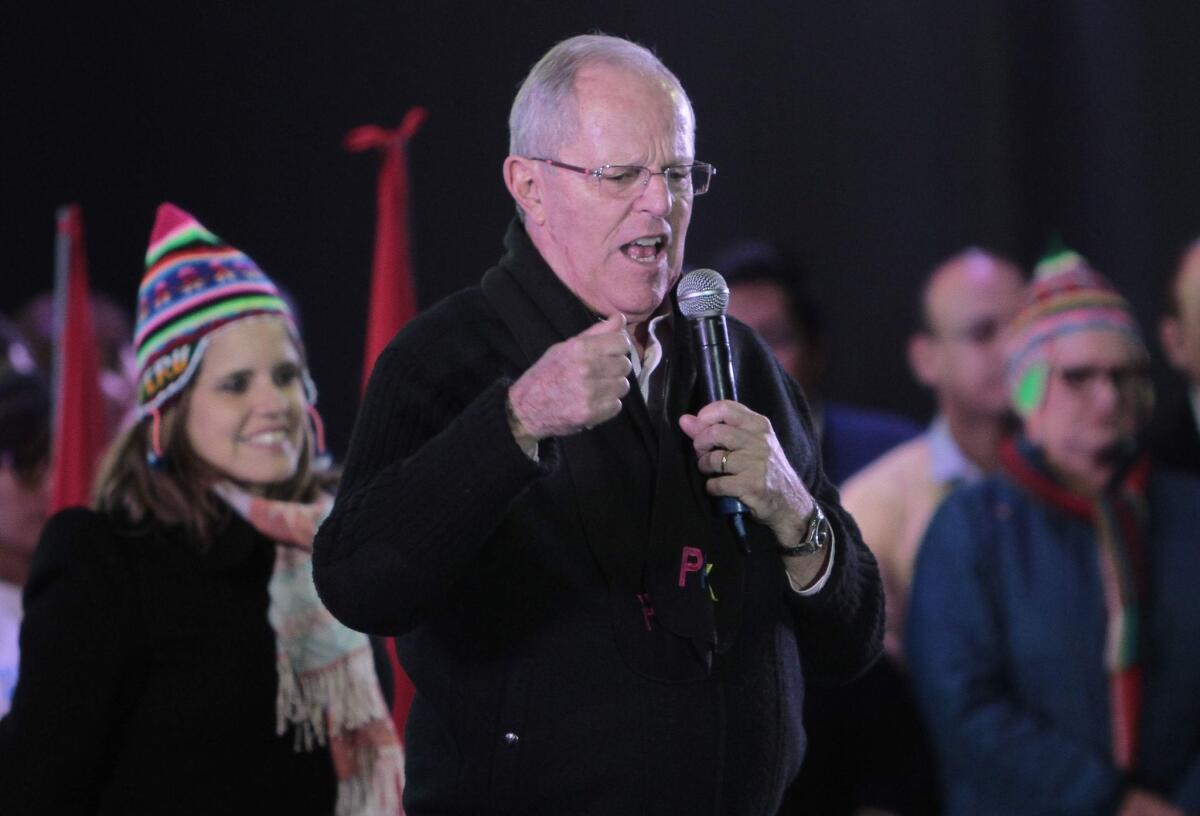

Her 77-year-old challenger, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, had performed abysmally in the candidates’ first debate and was hurt by his decision to spend a week during the campaign in the United States to attend his daughter’s college graduation.

But things have gone Kuczynski’s way in recent days, and Sunday’s presidential election is now too close to call, analysts here say.

Surveys taken in the campaign’s waning days show that Fujimori, a congresswoman and daughter of disgraced former President Alberto Fujimori, and Kuczynski, a former finance minister, locked in a technical tie.

Several factors combined to buoy Kuczynski’s candidacy.

The former World Bank economist improved his performance with a more aggressive approach in a second debate and received the backing of Veronika Mendoza, the socialist member of Congress who finished third in April’s first round of voting.

PPK, as Kuczynski is known, also has picked up endorsements from well-known Peruvians, including Nobel Prize-winning author Mario Vargas Llosa, who ran for president against Fujimori’s father in 1990, and former U.N. Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar.

Also in Kuczynski’s favor is many Peruvians’ abiding animus toward Alberto Fujimori, who was sentenced in 2009 to 25 years in prison on charges of crimes against humanity and corruption. He also has been accused of approving the sterilization of 300,000 women, most of them indigenous, during his time in office from 1990 to 2000.

Residual resentment against her father was blamed for Fujimori’s losing the presidency in 2011, when she was beaten in a runoff by Ollanta Humala after handily winning the first round, much as she did in April against six opponents. Fujimori captured 40% of the vote and Kuczynski 20%.

See more of our top stories on Facebook >>

Last month, Fujimori’s campaign had to deal with news reports that the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration was investigating one of her advisors, Joaquin Ramirez, in connection with a money laundering scheme.

From Washington, the DEA issued a statement May 16 saying that Fujimori “is not currently, nor has been previously” investigated, but the ongoing controversy that has been kept alive by opposition media has not helped her.

“My conversations with well-plugged-in folks here suggest that there has been some significant movement toward PPK and that the latest polls show Keiko has lost all of the 5[%] to 6% advantage she had just a few days ago,” said David Scott Palmer, a Boston University international relations professor and Peru expert.

Whoever wins, a new centrist president will replace left-of-center incumbent Humala, continuing a recent trend by which leftist regimes in Latin America are being replaced by market-friendly leaders promising fiscal responsibility and better security.

Fujimori has worked to erase the stigma of her last name, promising not to repeat her imprisoned father’s authoritarian ways, and to never grant him a pardon. At the same time, she has leveraged the positive perception many poor Peruvians retain of him for having built schools, clinics and roads in rural areas and for vanquishing the Sendero Luminoso, or Shining Path, rebel movement.

Her broad base of support was illustrated in April’s election when her party, Force Peru, won a 73-seat majority in the 135-member congress.

In what analysts describe as populist moves, Fujimori has tried to bolster rural support by saying she would legitimize illegal mining. Many Peruvians prospect for gold illegally in mountain areas, and Fujimori has promised to formalize that business activity.

She also has sought the support of Peru’s sizable conservative evangelical community by coming out against same-sex marriages.

But longtime Peru researcher Shane Hunt says Fujimori has grasped that the main issue for voters during this election cycle is the country’s deteriorating security, a byproduct of Peru’s role as a cocaine-trafficking hub. Crime is an issue especially important to poor voters, who suffer the brunt of the upsurge in violence.

“She doesn’t talk about human rights; she talks about getting tough on criminals, including building five new high-altitude prisons and calling the army and navy into the fight,” said Hunt, who is professor emeritus at Boston University. “In other words, going after the crime problem the way her father went after the Sendero. By so doing, she captures the anger of the poor.”

Hunt added that Fujimori and Kuczynski have said little about making changes in Peru’s economy, which is one of South America’s best performing. The inflation rate of 3.5% is among the lowest in the region, and the economy is expanding at a 4% rate, growth that Fujimori has claimed as a legacy from her father’s reforms.

“Who wants to fix it if it ain’t broke?” Hunt said.

Kuczynski, meanwhile, has overcome concerns about his age — concerns heightened during his first debate with Fujimori when he came across as doddering and unfocused.

“Kuczynski’s biggest negative has been his age. He just didn’t seem to have answers to Keiko’s criticisms or be able to stand his ground,” said George Washington University political science professor Cynthia McClintock, commenting on the former minister’s first debate performance.

But Kuczynski exploited Fujimori’s vulnerabilities in what most observers say was a good performance on May 29 in their second and final debate.

He attacked her for advisor Ramirez’s alleged narco connections and reminded viewers that her father was convicted on charges of authorizing death squads and suggested he had a role in the mass sterilizations.

“Sadly, there was a lot of corruption in the government of your father, and that’s one of the reasons he is a prisoner today,” Kuczynski said.

While Boston University professor Palmer said Kuczynski “definitely made up lost ground,” it remains to be seen whether that and the “DEA stuff will push him over the top. … It will certainly be a close race.”

ALSO

Pope approves measures to oust, but not prosecute, bishops who botch abuse cases

A tiny museum in Hong Kong fights to reclaim the memory of the Tiananmen Square uprising

Flooding in France kills more than a dozen people and forces closures of roads, subways and museums

Special correspondents Leon and Kraul reported from Lima, Peru, and Bogota, Colombia, respectively.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.