Welcome to the Olympic Games. In case you never heard of me, I am Brazil’s president

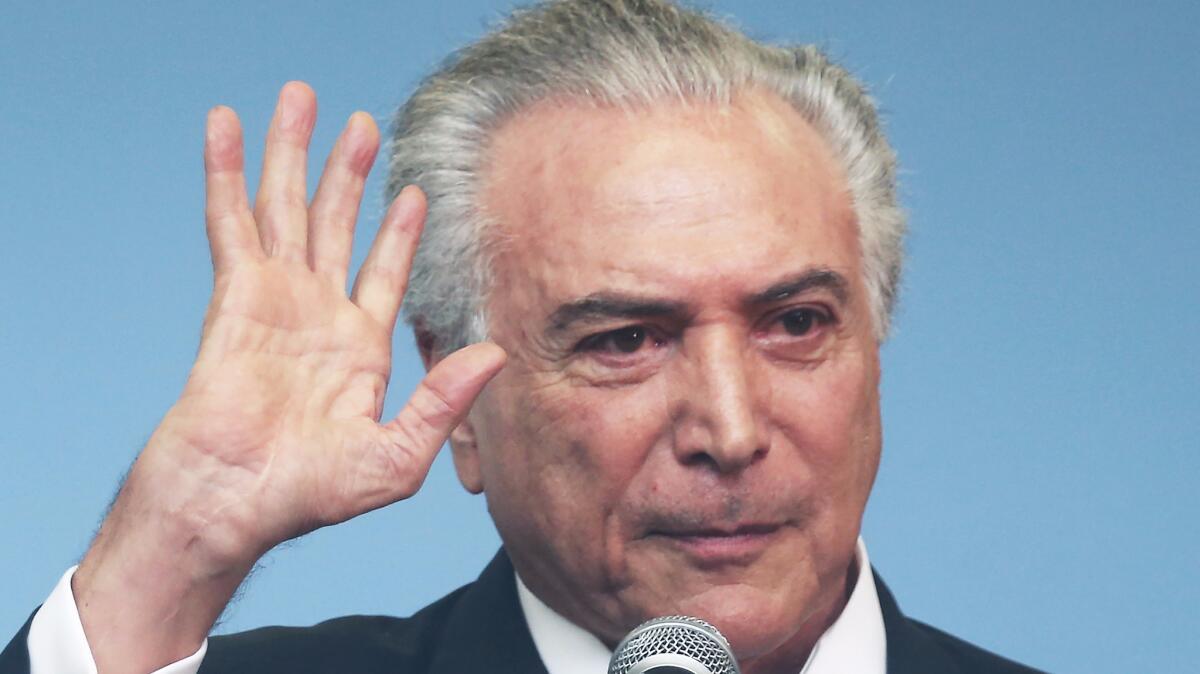

Brazil’s interim President Michel Temer.

- Share via

Reporting from Rio de Janeiro — “I declare open the Games of Rio, celebrating the 31st Olympiad of the modern era.” These are the words Brazil’s leader must pronounce at the opening ceremony of the Summer Games.

But when interim President Michel Temer utters those words at the historic Maracanã Stadium on Friday night, the international audience may well wonder: Who is that guy? As for the Brazilian audience in the stadium, Temer said that he is “extremely prepared” to be booed.

Quoting a famous Brazilian author, he told local media: “As Nelson Rodrigues said, at the Maracanã they even boo the moment of silence. I have to carry out my institutional duty.”

A few months ago, Temer was vice president, serving under President Dilma Rousseff as she attempted to weather an epic economic and political crisis. After he turned against her, however, she was eventually impeached and removed from office, pending a Senate trial later this month.

Temer, a 75-year old lawyer, has turned the country sharply to the right since taking over in May and has been accused of gaining power through a nonmilitary congressional “coup.” Now he presides over an unpopular government and will be at the helm of an Olympics that, many Brazilians believe, are a waste of taxpayer money.

“It’s ridiculous. They’re throwing money out the window, and that’s money we need for basic services,” says Jonas Cardoso, 47, who has worked a series of odd jobs in recent years and is today serving drinks on Copacabana beach. Recent polling shows Brazilians think the Olympics will do more harm than good.

“When they declare the Games open, the Brazilians in the stands are going to boo,” Cardoso said.

Still, Brazilians and observers of Latin American politics will be watching the opening ceremony and the subsequent festivities closely, waiting to see how they may affect the fragile situation in South America’s largest country. Not only are many Brazilians indifferent or fed up with the Olympics, but a majority of Brazilians want Temer out of office and less than half of the country sees impeachment and impending regime change as constitutionally legitimate.

Experts believe that Temer will try to use the Olympic spotlight to solidify his role as president, that his opponents will use the same spotlight to question his legitimacy, and that the first Olympiad in South America could easily join the annals of other politically fraught Olympics.

“What we’re seeing in the lead-up to the Olympic Games is unprecedented. In terms of politics, the impeachment, and the economic situation, this is new,” said Jules Boykoff, author of”Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics.” “But there have been other Olympics that took place in moments of crisis.”

He pointed to the 1968 Mexico City Games, which took place after a massacre of protesters destabilized the country. That Olympiad also famously featured the raised-fist, “black power” salute by Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos that became an enduring global symbol of resistance.

In Rio de Janeiro, which has seen the influx of tens of thousands of heavily armed security officers to patrol the streets, attitudes towards the Games range from mild excitement to aggressive indifference.

“The Olympic Games? Who cares about them? I’m not going to be watching. I need to be working,” said Margarita dos Anjos, 69, who owns a small restaurant in Rio. As she serves simple grub to construction workers, a flood of tourists heads past her door toward the massive official Rio 2016 tourist shop, where they can buy a soccer ball costing more than a third of the monthly minimum wage.

Recent polling indicated that a majority of Brazilians said they had little or no interest in the Games. But talk of politics gets Dos Anjos fired up. “Look, Brazil is a marvelous country, that’s true. But all of our politicians are crooks. Shameless crooks,” she said.

When the leftist Rousseff attended the opening match of soccer’s 2014 World Cup, she was booed heartily by largely wealthy fans in São Paulo. Despite the fact that she was still relatively popular at the time, the moment helped define the political conversation here over the last two years, and the growing divisions between the poor and the left on one side, and the upper-middle class and conservatives on the other.

Rousseff’s popularity tanked with the economy after she won reelection in late 2014, and calls for her ouster were ultimately successful. But only a tiny minority actually wanted her replaced by Temer. For better or worse, the interim president does have the backing of Congress, a majority of whose members are accused of corruption or other serious crimes.

The result has been a mess of deadlock and resentment. A recent poll registered Temer’s approval rating at 11%. Rousseff says she won’t attend the Olympics she helped plan, refusing to play second fiddle to a man she considers a putschist. Some global leaders are staying away from the political minefield, and U.S. unions and liberal House Democrats have asked Secretary of State John F. Kerry, who will attend Rio 2016, not to legitimize the Temer government.

The content of the opening ceremony itself is tinged with uniquely Brazilian political history. Fernando Meirelles, the director of the performance, is responsible for “City of God,” one of the most popular Brazilian movies of the 21st century. The movie traces the indifference of the government toward the poor in the city’s favelas, or slums, and how the communities explode into violence as drug-trafficking takes over.

Crime has risen as the state went broke earlier this year, and critics have accused the Games of diverting resources from schools and police.

“I think this government is completely illegitimate,” says Carol Gomes, 27, who works in advertising in Rio de Janeiro and is active in feminist protests. “Even if I could afford to get into the Maracanã, I wouldn’t go. I can’t sign off on what they’re doing.”

Bevins is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.