Prosecution of a long-ago murder sets off a debate in China

- Share via

MASHANG VILLAGE, China — The last time they saw their father, Hong Yunke, he was leaving home, hauling his wooden medicine chest, on a frigid December morning in 1967.

“I’m going to treat a patient and collect money,” Hong told his son, 12, and his daughter, 9. “I’ll be back soon.”

Hong was what the Chinese call a barefoot doctor, a self-educated healer who treated the sprained ankles of farmers for 20 cents, enough in those days for two pork buns. His wife, unable to endure the poverty, had left him to raise the children on his own.

No matter. As a doctor, he was considered a “class enemy” by youthful Red Guards unleashed by Mao Tse-tung at the start of the Cultural Revolution. Having stumbled into the clutches of a particularly cruel gang, Hong was strangled with rope and his legs were broken; his body was stuffed into a hastily dug mountainside grave. Buried, but not forgotten.

One might say that Hong’s ghost has risen, bringing back to life a debate about whether justice was served after the bloody Cultural Revolution ended.

One of the former Red Guards, Qiu Riren, was sentenced to 31/2 years in prison in late March by a court in Ruian, in the eastern province of Zhejiang. The 80-year-old defendant had been arrested last year on a decades-old warrant and admitted guilt during a one-day trial in February.

Two other participants were convicted of the killing in the early 1980s, but at the time Qiu’s whereabouts was unknown.

It is rare in China to prosecute a crime committed so long ago, much less one that occurred during the Cultural Revolution. Historians say 750,000 to 1.5 million people were killed in the decadelong spasm of violence, but the subject is something of a black hole in history books, and many Chinese who experienced or participated in the terror still maintain a stony silence.

But Ruian was something of an exception. Its prosecutors launched an investigation in the 1980s of some of the more egregious cases, including the slaying of Hong.

The recent prosecution has galvanized the Chinese public, setting off a rare debate in intellectual and legal circles about the violent era and whether low-level participants should still be held to account.

As with the prosecution of elderly Nazis, defenders of the Red Guard insist its members were merely following orders. After all, it was Mao himself who unleashed the terror, refusing advice to rein in the excesses, and who was once quoted as saying, “The more people you kill, the more revolutionary you are.”

“Why are they prosecuting this ordinary person when so many of the real culprits of the Cultural Revolution went free?” said Liu Xiaoyuan, a prominent Beijing human rights lawyer.

But Hong’s survivors would like full retribution.

“My father died a very violent death. I would be happy for his murderer to get the death penalty,” Hong’s son, Hong Zuosheng, said at his home in Mashang, a village surrounded by yellow-blooming canola fields about 300 miles south of Shanghai.

Like his father, Hong treats leg injuries with traditional medicine, but he never went to school — it was unthinkable financially after his father was slain — and he can barely read the legal documents that prosecutors gave him. With heavy bags under his eyes, he is a reticent man — his wife finishes many of his sentences — but he makes it clear that his life was clouded by the killing.

“My sister and I were very poor after our father was killed,” he said. “My grandfather raised us.”

Hong’s family was so terrified that they dared not retrieve his body right away. His son waited three years, until he was 15. Mountain residents showed him the burial site, and he exhumed the remains.

Later, Hong learned who was responsible for the crime.

“You see that guy — he’s one of those who killed your father,” people would sometimes tell him. He would occasionally see Qiu Riren, who was from another village but had married a woman from Mashang. Hong didn’t confront anyone at the time; instead he averted his eyes and walked away.

The Cultural Revolution ended with Mao’s death in 1976. People who had been wrongfully prosecuted had their convictions overturned and were rehabilitated into society. Leaders of the revolution, the Gang of Four, which included Mao’s widow, Jiang Qing, were prosecuted.

But the courts rarely went after the Red Guards.

“Some people said we ought to investigate murders committed by the Red Guards, but others said, ‘Better not, they are probably our children or our relatives,’” said Zhang Lifan, a Chinese historian.

In Ruian, however, charges were filed against three former guards in 1986, just before the expiration of China’s statute of limitations. The two men who were convicted received sentences of 1 1/2 and seven years.

Qiu comes from Huangshe village, about five miles from Mashang. He was in his early 30s at the start of the Cultural Revolution, older than other Red Guards, and was active in one of two rival militias that were battling for power during the period.

In 1982, he left his village, perhaps to escape prosecution but more likely swept along by the tide of migrant workers partaking in the boom brought about by China’s economic reforms. For decades, he never came back to visit, not even for Lunar New Year.

Finally, on a hot July afternoon last year, several men were playing cards in the shade of a banyan tree in Huangshe, a village about five miles from Mashang, when police brought a shabbily dressed elderly man by. They said the man had been wandering, homeless and begging, in a nearby town.

“It wasn’t until we talked for about half an hour that we figured out he was Qiu. Even his own brother didn’t recognize him,” said Li Mingxi, 62. “Everybody thought he was dead. It had been 30 years and nobody had heard from him.”

Qiu told the villagers he’d been doing odd jobs and construction work and now wanted to spend his final years at home in peace. But just six days after his return, he was served with the 1986 arrest warrant. The charges were still valid because they had been filed before the statute of limitations expired.

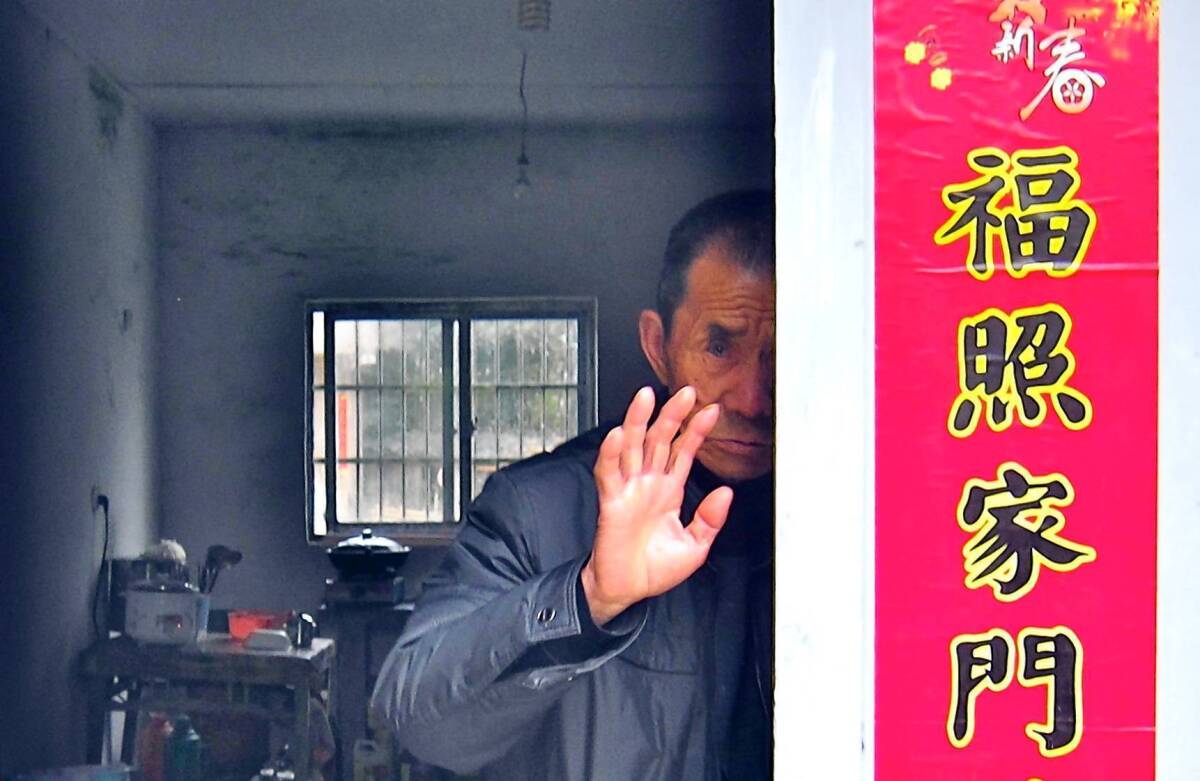

Although now a convicted murderer, Qiu is still living in the village, alone in a bare concrete house built for him by his family. A tall man with soldier-straight posture and a brush of dark hair, he scowls from the doorway at visitors, shooing them away with his hands.

Whatever Qiu thinks of the murder case, he is unable or unwilling to say.

“I don’t understand,” he tells anybody who approaches to pose a question. “I can’t hear you.”

Qiu barely spoke during the Dec. 21 court hearing, to the disappointment of Hong’s relatives, who had expected at least an apology. He did, however, concede the facts of the case, as described in witness statements dating to the 1970s.

The elder Hong apparently knew Qiu and had pleaded with him not to let the others kill him. The Red Guards told Hong he was “not good enough to waste a bullet” on, according to witness statements filed with the court. Hong was apparently not yet dead when his bones were crushed and he was folded into the grave.

Before Qiu left the crime scene, he took a moment to steal Hong’s ballpoint pen and enough money to buy a pack of cigarettes.

Today Qiu’s relatives just want the old man left alone.

“We didn’t know where he’d been or what he’d done, but we were happy to get our relative back,” said Wu Chenlei, a great-niece, who was visiting the village last week for a family funeral. “As far as we’re concerned, he’s also a victim of the Cultural Revolution.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.