Mexico’s political left unable to derail Pemex legislation

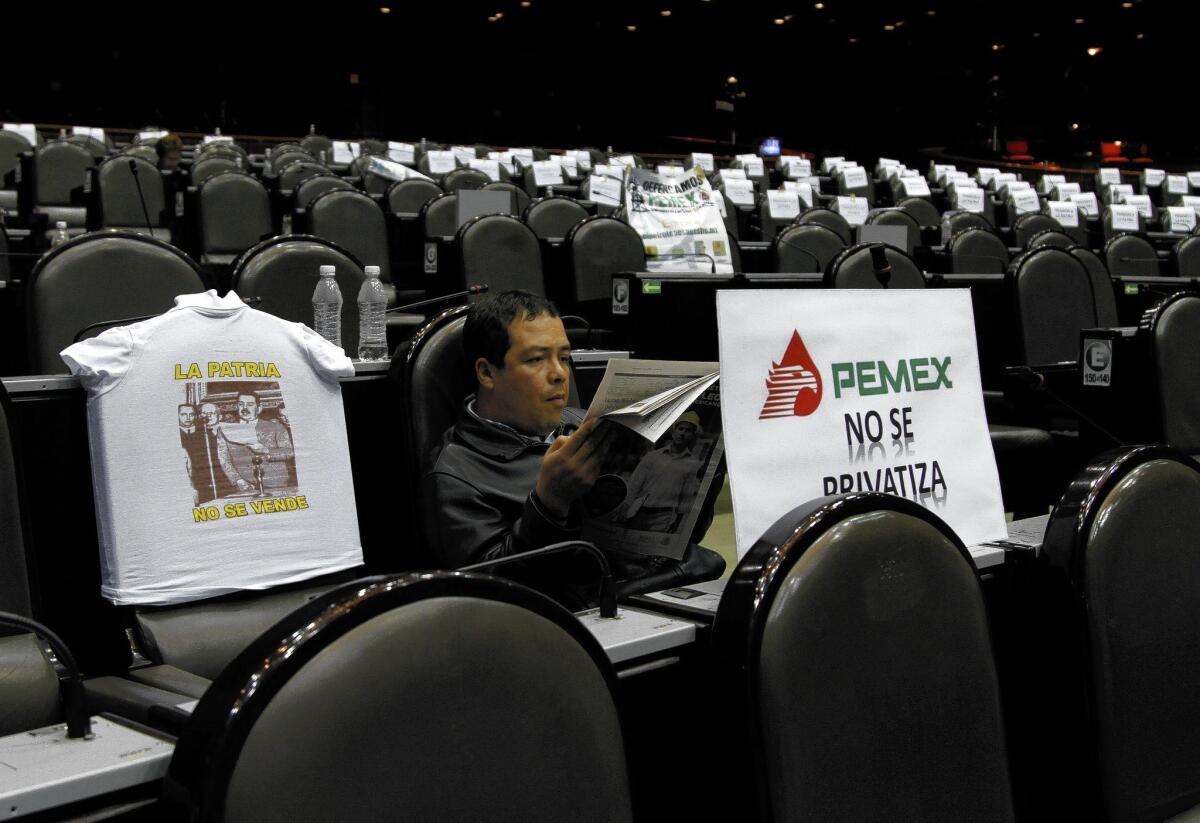

MEXICO CITY — Mexico’s leftist politicians have watched hopelessly in recent days as a center-right coalition secured passage of a sweeping energy reform bill that will allow foreigners to drill for oil on Mexican territory for the first time in several decades.

It was a move that once would have been unthinkable in a country that still celebrates the 1938 nationalization of the oil industry with a national holiday. And it remains a sore topic for many Mexicans: In a nationwide poll released in June, 65% said they opposed opening Pemex, the state-run oil company, to private investment.

The failure of Mexico’s leftist leaders to capitalize on that sentiment is the latest setback for a movement that can still jam the streets with thousands of protesters but has struggled in recent years to yield real power. A leftist party has yet to win a Mexican presidential election in this young century, despite a national poverty rate hovering just under 50% — and despite the wave of neo-Marxist enthusiasm that has swept across other Latin American countries, including Venezuela, Bolivia and Brazil.

Given their numerical disadvantage in Congress, leftists had little chance to thwart the move. An alliance between President Enrique Peña Nieto’s centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, and the conservative National Action Party, or PAN, allowed the bill to easily achieve the two-thirds majority needed for passage in each house of Congress this month.

The legislation ends the petroleum and electric companies’ 75-year monopoly, allowing private oil firms, including the big U.S. conglomerates, to enter into “production-sharing” agreements with Mexico.

Mexico’s left-wing politicians maintain that their fight against energy reform has only just begun. But opponents question their ability to roll back legislation that cleared its final real political hurdle last week when it was approved by a majority of state legislatures. A split in the leftist movement after last year’s presidential election is also likely to complicate their cause.

Leaders of the main left-wing party, the Democratic Revolution Party, or PRD, have said they will ask the Supreme Court to overturn the reform. They are also pinning their hopes on a new law that allows for referendums on matters of national importance, and are telling voters they will have a chance to reject the energy reform during July 2015 elections. But the constitutionality of that effort is in dispute, and probably will be settled in the courts as well.

Meanwhile, the breakaway Movement for National Regeneration, or Morena, — created by former PRD presidential candidate Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador — sent its followers to state legislatures to form human chains around the buildings as lawmakers voted on the bill. Some scuffled with authorities, but it proved too little too late.

For months here, it was assumed that the left, despite its congressional minority, might be able to sway the debate with massive protests. But as Congress was debating the bill, a number of observers noted that street protests in Mexico City were not as large as expected. That may have had to do with the fact that the charismatic Lopez Obrador, 60, was recovering from a heart attack and sidelined from politics, or because the bill’s proponents timed the deliberations in the Christmas season, when politics, for many Mexicans, takes a back seat to family and fiestas.

Mexico City pollster Jorge Buendia is among those who doubts how deep the anti-reform sentiment actually goes among Mexicans, given the state-run oil company’s reputation for internal corruption and rewarding the well-connected.

In recent focus groups, Buendia said, he asked participants their opinion about the left’s common refrain “The petroleum is ours,” a battle cry based on the guarantee in the Mexican Constitution that the people are the owners of subsoil oil and gas.

“People would say, ‘Ours? When have I received something from Pemex? Gas is very expensive, and I’ve never gotten a dime from Pemex!’” Buendia recalled.

Though energy analysts have said that Mexico needs foreign investment and expertise to reverse declining oil and gas production, leftists here counter that Pemex could prosper by modernizing its practices and addressing corruption. The leftist groups also say that Mexico has failed to benefit from privatizing other state-run industries, a strategy championed in recent years by the PRI and PAN.

Many people may agree with such sentiments, but their numbers are now divided between two leftist groups. Lopez Obrador split from the PRD after losing the presidential election last year. He later criticized the PRD for entering into a so-called Pact for Mexico with the other two parties shortly after Peña Nieto’s inauguration in December 2012.

Under the pact, the three parties agreed to work together to pass major reforms in Congress. (The PRD recently dropped out over the energy reform bill, which PRD president Jesus Zambrano views as a violation of some of the basic tenets.)

And so, as Congress debated the bill, there were two separate protests on the Paseo de la Reforma, Mexico City’s grand boulevard: The PRD supporters marched around the iconic Angel of Independence statue, while a few blocks away, Morena backers gathered in front of Senate headquarters, bashing with rocks and hammers on the metal barriers surrounding it.

A protester at the PRD rally, Julio Jimenez, said he was holding out hope for a victory despite the challenges.

“Yes, the left is divided,” the 55-year-old economics professor said as he marched with a few dozen fellow protesters. “But we are also right about this.”

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.